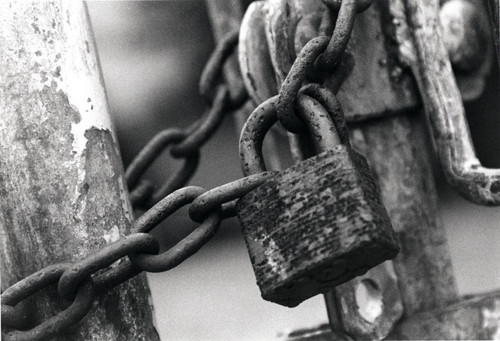

Locked to the Cloud

We have wanted to implement full text search on our site for a while. The recent announcement by Amazon of their new CloudSearch made me wonder, should I jump on this excellent offering? It appears that it might be a little expensive, but what is the cost of rolling out our own search engine?

Then once the temptation had loosened its grip I started wondering about the hidden costs of being on somebody else’s cloud. When moving our services to the cloud it is too easy to get locked in with one provider. We may even have to forget about the option to acquire and use our own servers eventually, should we ever want to. What can we do to increase our options? We are going to dissect three possible strategies: evaluation, migration and encapsulation.

Evaluating Lock-in

Lock-in effects are in general terrible: you are stuck with one application, framework or whatever piece of technology for the foreseeable future, or have to pay a high price to get off them. The worst part of lock-in is that you start suffering it without any noticeable symptoms: things just work as usual, until you want to switch it. In fact you may not even know that you are locked in to one particular technology since maybe you don’t know (or care) about alternatives at all.

Cue inevitable car analogy: think about car transmissions. In the US automatic transmissions are hugely popular, to the point that drivers may not even be aware of what manual transmissions are capable of. Switching to a manual transmission is hard: many people are not willing to learn how to use the new clutch. When a customer is purchasing a new car they are unlikely to realize that there is an implicit lock-in due to the learning curve. In Europe manual (or rather pedal) gears are the default, and changing gears correctly usually takes a few driving lessons. Automatic transmissions are widely known and even offered as an option by most car makers; and yet most buyers just disregard it as a useless American gadget. Here the lock-in to manual is more explicit, but few people care about it.

In both regions most people ignore that there are elegant alternatives such as the semi-automatic transmission found e.g. in Smart cars: they allow for the same degree of control as manual gearboxes but do not require the driver to press a clutch. Due to technology lock-in very few models even offer the possibility, and customers do not seem to care at all; no matter the advantages (or disadvantages) that this third option might bring.

Technology lock-in can be hard to see. Vendor lock-in is much easier to identify: after all there is a vendor trying to sell something, and there are usually plenty of opportunities to notice it. When evaluating a product, one of the key aspects to look for is whether there are alternatives and whether they provide the same level of support. But the product will probably be in use for a very long time, and the situation is likely to change: what was once a product with several suppliers can become a huge lock-in factor, and viceversa.

Migrating Away

When talking about services instead of products, lock-in effects are even more intangible. Is anyone else providing a compatible service now? Will they be interested to in the future? And there is an additional question: can we provide the service for ourselves? Alternatives are quite unlikely to be exactly the same: at the very least the web interface will probably be different.

And there are always additional services to consider. Many providers offer features that distinguish from the competition. While the main offering is often standardized, these other complements are specific to each provider, and can be burdensome to change when switching to the competition. Service lock-in is no longer an all-or-nothing issue, but a gradual addition of locking-in factors.

Take github: they provide an awesome service for git hosting. They also provide additional services like issue management, a wiki and a few more. It seems only good business sense to use those services since we are already paying for them. But github is not perfect: there are glitches from time to time which cause our automated processes to fail, and we have to provide for their failures. Also, we are not happy (or legally allowed) to host certain files on someone else’s servers so we have to distribute them off-band, which is a bother.

The question has arised in the past: couldn’t we self-host our git repos? Yes, but we would lose all of the associated services, like the wiki. Could we self-host the wiki too? All wiki pages can be exported as a git repo so lock-in is not too bad, but it would take us some more effort. The barriers for change pile up until it becomes a major project just to switch services – or self-host our own. So we use as few as possible of github services, contrary to traditional business sense; and as a result we have a clear migration strategy.

Encapsulation

Now we move to cloud computing, which in essence means you are just renting a virtualized machine in someone else’s datacenter. Where are the lock-in effects here? As has been argued, using the cloud itself does not imply lock-in: a lot of providers rent virtualized servers. It would be nice to be able to export system images (what Amazon calls snapshots) from one to the next, but you should be able to build a server from scratch almost automatically anyway. And then there are additional services like CloudSearch which started this article.

Each individual service can be encapsulated to simplify the migration strategy: instead of having to make small changes throughout our web application there is a single funnel that can be easily adapted to a different provider.

At MoveinBlue we use several Amazon services, like Simple Email Service (SES). Could we send our own email messages? Sure, but then we would have to deal with a lot of nasty stuff such as spam filters. So in order to reduce lock-in to the minimum we send all our mail through a single PHP service, which can be easily replaced with a different one that uses a different provider – or communicates with our own SMTP daemon.

When to Open Your Options

The benefits of avoiding lock-in are in the future, and intangible by nature: just an option to keep alternatives open in the future. See the triple use of conditional words here: option, alternative, future. Plausible alternatives may or not exist in the future, they may or not be convenient and the buyer may or not want to exercise those options at all.

“Keep your options open” is not always good advice. Sometimes there is really just one option and you have to bite the bullet and go with it. At other times the eventual benefits are so far away into the future that it is best to go with a vendor and leave the lock-in worries for the future you (or even your successor). Probabilities can be evaluated (implicitly or explicitly) to reach a veredict, but in the end there is often nothing better than a gut feeling to guide us.

Even worse, the decision to keep alternatives open cannot be evaluated based solely on the result. Hindsight is not 100% accurate as the saying goes: a rational decision can be the best answer at the moment but produce the wrong consequences. This happens a lot with decisions based on statistical arguments.

Imagine you are a doctor prescribing an intravenous antibiotic for a patient suffering an accute infection. The patient, as it turns out, is allergic to the antibiotic and dies. Was it the best course of action? The family will probably question the decision, but it just happens that 1 in 100k people is allergic to that particular antibiotic; the decision was right but the outcome was wrong. This is the type of reasoning that those in the anti-vaccination movement have a hard time understanding: a vaccine can be good for society even if a few individuals have violent reactions to them, and the alternatives (periodic epidemic outbursts) are a hundred times more horrible.

We can evaluate our options at a given time, choose to keep them open, and make a big mistake since the closed option is much better five years down the road. Conversely, we can choose lock-in and have a great experience with our vendor. This does not make those decisions any better or worse.

What Can Possibly Happen?

Now we enter the category of “famous last words”. Companies evolve, management changes, businesses are bought and sold and last week’s friend can be this week’s Scroogey landlord. Your company probably wants to stay around for a long time, and in online businesses trying to guess what might happen next year is mostly futile. But there are clues all around.

When people started using the Google App Engine (GAE) it seemed like too good to be true: a completely managed platform run by the developer-friendly Google, which they could use for very little money. And it was too good to be true: at some point the big price hike hit many people with 10x price increases, and Google started marketing it as a premium service (only they had been so nice as to let developers use it dirt cheap before). Moving off GAE was really hard since developers had not taken into account those little details that make a web application scalable… because they previously had no reason to care.

The only way to avoid suffering sudden changes of conditions is to make sure that you leave your options open. But the pain can be alleviated: if you have to be locked in, at least make sure that you have evaluated the risks, know your way in and your way out, and encapsulate all the external services that you can.

A single service like Amazon SES can be encapsulated; a complete framework like GAE cannot. Also, GAE cannot be replicated since Google does not provide its source code. In retrospect its users were a bit unlucky since Google changed heart quite suddenly, but it was also a wake-up call. Using GAE was never a sensible business decision: there were (and there could not be) competing services, a migration strategy would be extremely painful and a whole platform could not be encapsulated.

Conclusion

From a business perspective, lock-in is just another factor to take into account when making a decision, and most business factors are inherently risky. To protect business from those risks there are also engineering choices: keep a migration strategy and encapsulate all the services that we may want to migrate. These choices may or may not be used in the future, but they are sensible anyway and easy to understand.

Saying “do not marry anyone” is probably useless once you have already decided that you want to marry. The take-away lessons can be summarized as:

- once you are engaged, consider the alternatives before the wedding;

- check out how hard a divorce might be and how much it will cost;

- and write down in a prenuptial agreement all the possible thorny issues that will make an eventual divorce easier.

Not very romantic for weddings, but very effective in engineering.