Should I Build or Should I Not

Or Pondering the Merits of Custom DevOps Tools

A Story for Builders

Before we start, let us clear the air. This is a story for builders, not for decisions makers. Therefore it may only be of interest to people in organizations where there is not a large divide between the two, or where the divide can at least be breached somehow. If that is not your case, I am not sure I can help you.

For decision makers, I should probably show you some cold and rational bullet points to help you decide if you want to build a custom solution or not. The problem here is that things are not as cold and rational as you would probably like.

Just run a detailed Total Cost of Ownership comparison. And then throw it away, because you will probably have left out some of the most important factors in the equation. In this article I will go over some of these so you can go back to ignoring them if you want.

Instead, I will start with a few case studies of my own, then try to debunk what many people take as “rational” arguments, and offer some emotional points which are really the best that I can offer you. After that we will see a third way which should hopefully act as a synthesis of previous arguments, and finally offer some conclusions.

Some Case Studies

I will now present a few examples that have happened in our daily practice at MediaSmart Mobile, the mobile adtech company I work at.

Continuous Deployment

Continuous deployment is perhaps the most important practice in DevOps: there are even voices saying that Agile is Dead, Long Live Continuous Delivery.

Continuous What?

Do not be fooled by the promises of continuous delivery though; it is just an imperfect form of continuous deployment, where software just reaches some sort of integration environment, and thus is nothing but continuous integration in more elegant clothing. Always request continuous deployment at your favorite shops, since the full advantages are not realized until all changes do reach production right after merging them.

Why deploy everything? The benefits for the team are multiplied:

- Fixes are instantaneous.

- The discipline to release is written in fire.

- Deploying in small increments, any brokennes can be quickly attributed and fixed.

Sometimes you really need to delay the release of a feature. Branches are the most obvious answer: develop your changes separately, and only merge when ready. But sometimes many people need to work on the new feature, or the feature may take long to develop, and branches may be inconvenient. There are several techniques that help get all the benefits of continuous deployment, without the drawbacks:

Feature flags: deploy the new feature disabled, enable with a switch (a setting or a config value).

Dark launches: deploy the new feature but do not tell anyone. Can use a feature flag, a secret URL or be visible only for certain users.

Canary deployments: enable the changes only for a subset of users, handpicked or random.

Custom Infrastructure

During the last few years I have helped build a few continuous

deployment systems. I drew my first inspiration from Allspaw and Robbins

in their excellent Web

Operations, and built a custom system for my own startup. The

technology was very successful but the company flopped. Since then my

first priority after starting work on a new project has been to set up

continuous deployment. Some of them were as simple as a PHP script that

invoked rsync, others have involved doing distributed

deployments to a variable number of servers. All of them have strived

for simplicity and efficiency.

At MediaSmart I convinced our CTO Guillermo Fernández to implement

continuous deployment after about 6 months in the company, and we have

lived happily ever since. Well, almost. At that time we had to deploy

our code to all four servers (!): ssh into them,

git pull and restart with supervisor.

The first iteration was a very simple script that distributed a command to all running instances on our AWS infrastructure. This script had to be launched manually. An improved version of this script is still in use, and has saved us a ton of work administering services.

The we migrated it to Node.js, and integrated it with GitHub webhooks. We have been using my own npm package for a few years: deployment, which has a simple command that creates a server and listens to requests; when the correct URL is invoked, it deploys code to the server. Then we did distributed deployments with a custom Node.js script, that reads the list of servers from an Amazon ELB, and then invokes the deployment server on each of the instances.

It had all of the rough edges of a custom tool: it was command-line only, had to be set up (with webhooks to GitHub) manually each time, had to be started up using Upstart tasks for Ubuntu. After three years I got tired of setting up deployment servers, and the whole infrastructure was becoming unwieldy. So we started looking for alternatives.

StriderCD

Luckily Juan Carlos Delgado, CTO at llollo.com, had told me about a new alternative written in Node.js in a private conversation.

Excited, I tried StriderCD for a freelancing gig I did the following month: it is a very nice Node.js solution which has a graphical interface, similar to Travis-CI. It automatically sets up webhooks, and even allows testing all PRs. Best of all, it has “continuous deployment” right in the title, which automatically won my heart.

Lead by our latest recruit Alfredo López, in a few weeks we had migrated almost all of our infrastructure to StriderCD, and it was a most interesting project. At this point we are still refining our continuous deployment, and are missing a few things, like the ability to send a diff of the deployed changes by email after each deployment. But mostly it has been a success.

ELB Balancer

Now let us see the reverse situation: going from a standard product to a custom solution. A month ago I published an article about this migration which contains far more detail than this summary.

ELBs Are Expensive

At MediaSmart we routinely process 300 krps (thousand requests per second), with an average of over 200 krps. We receive over 16 billion requests and serve up to 30 million impressions each day. With these volumes costs can easily add up.

Amazon AWS Elastic Load Balancers have allowed us to grow quickly, but they were representing too much of a burden: they were eating up 20% of our monthly AWS bill. So we convinced Noelia, our CEO, to switch to a custom solution.

Nginx to the Rescue

We evaluated several open source products, starting with HAProxy which I had successfully used in several projects. We selected Nginx as our reverse proxy since it is easier to configure and use.

Server cost has gone up, of course: after all, Nginx has to run somewhere. But by reusing our filter servers this cost is almost negligible.

Just installing Nginx was not the whole story. What about the balancer stuff, sharing requests between a bunch of server? We switched to a DNS balancer: when the registry contains a number of servers, it automatically reorders it randomly for every request, so that every client will connect to a different server.

So we had to adjust our whole infrastructure to add and remove servers using the DNS registry. Luckily we were already using our own orchestrator, which allows us to make better use of our servers than the AWS Autoscaling Groups; one less thing to do.

Lua Logging

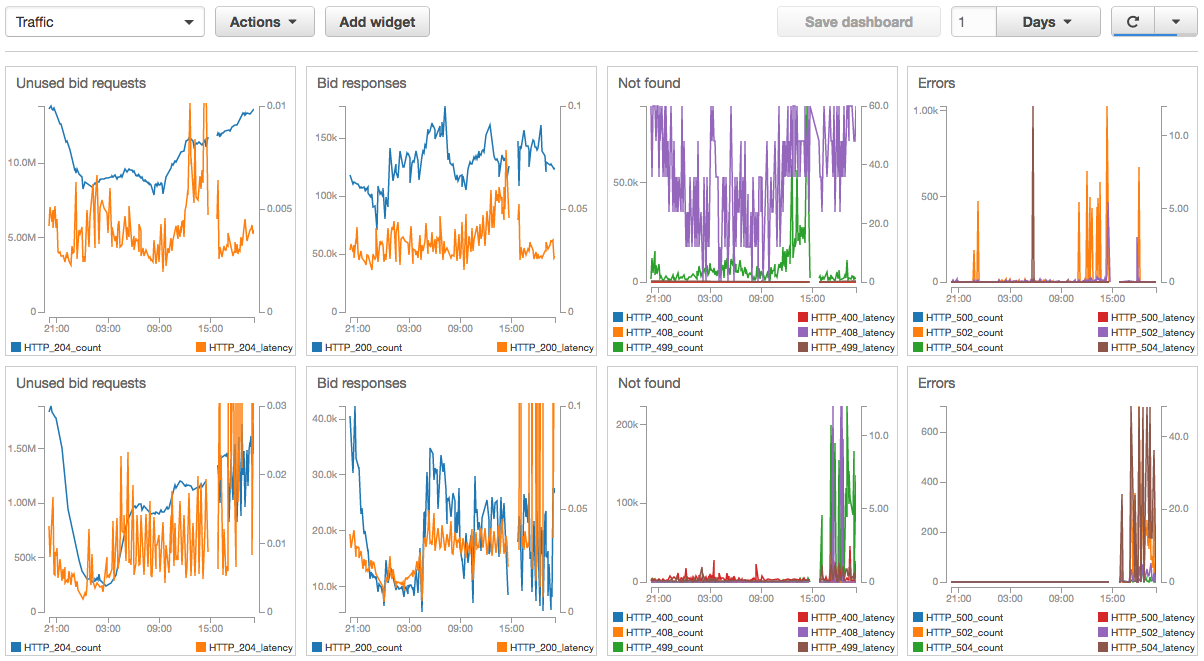

At this point we were still missing out on an important piece: logging and reporting. ELBs come with shiny graphs, and we did not want to lose those; if anything, we wanted to improve them.

So we hacked together a custom logging solution in Lua, the language that Nginx supports. It is super-fast and has caused zero problems in the months that it has been deployed. And unlike ELB reporting we can see different HTTP codes separately, which has allowed us to improve our response to problems.

To this day I have a server which has processed about 40 billion requests without skipping a beat. And more importantly, we have reduced our AWS costs from about 10% to 8% of our revenue.

Monitoring

Now let us see a mixed example, with standard and custom solutions.

We have several monitoring tools in place, which act as our eyes. We also have alerting systems, which are like our pain receptors.

We use Cloudwatch for basic systems monitoring and alerting. But it falls short of our needs in many respects, since it only reports CPU usage.

Early on we started building our infrastructure using Node.js: very basic alerts for disk space, memory and so on. Then we expanded on it with Redis usage alerts. Gradually it became more complex, reporting on site up / site down, log errors and so on.

Our CEO, Noelia Amoedo, has amazing attention to detail. So every once in a while she would come to us with questions like: why has the CTR on this particular exchange fallen so much? At other times it would be our business analyst, Tiago, who would alert us on small revenue or no conversions. Since we wanted to learn of problems before they told us, and realizing that checking business parameters must be a huge burden for them, we created Business Alerts, nicknamed the “Automatic Noelia”: a periodic check of business parameters, which would alert us when they differed too much from the previous day and the previous hour.

We might use a standard solution such as Nagios or Icinga for the middle monitoring layer. There is however no commercial or open source solution for our particular business case, so for business alerts there was only one option: build a custom solution.

Business Partners

Our company, MediaSmart Mobile, has been in talks with many other companies to create partnerships. Some of them do not like it too much when they learn that so much of our infrastructure is custom-made, instead of marvelling at our inventive.

Well-known products give security to people. It happens when buying brands at the supermarket, and also when choosing business partners.

One particular partner requested that we use Jenkins and Icinga before they did business with us. We took a look at them, and did not like what we saw: large monolithic projects which are a pain to set up and use.

It is not that we dislike existing products; but given the option we prefer small, flexible products whenever possible. Flexibility is one of our strenghts as a small company, and giving it up would probably be a bad idea.

At present we are doing business with this particular partner, although not as extensively as we would have liked.

Rational Arguments

I am a firm believer in rational thought: thinking things over objectively is our best tool at our disposition. The problem is that rational thought does not come naturally to people; our minds need to be trained very thoroughly if we are to remove subjectivity from our reasonings.

In this section we will see some arguments that are often used in this discussion, and that are supposed to be objective and rational. We will then deconstruct them to see that they are not as rational as they were supposed to be.

Robustness of Commercial Solutions

Bosses tend to trust commercial products all too much. After all, their thinking goes, if a prestigious company is offering a product it must be good indeed. But alas, shoddy products are the hallmark of our industry.

Maintainability

Maintaining a third-party product must surely be easier than a bunch of custom code hacked together by your predecessor.

Except for that time when your vendor stops supporting your product and forces you to upgrade, just because they want to make more money off you.

Technical Debt

Once you start a software project, you start accruing technical debt. It is almost inevitable. Infrastructure projects are usually the worst, so by the time that your DevOps infrastructure is functional it is an iceberg of debt waiting to fall on you.

Here we are gleefully ignoring the technical debt that actually exists in third party projects, just because we cannot see it. If your dev team is worse than the vendor this argument may carry some weight, so the moral should not be “do not build anything”; rather, “get a good dev team”.

Emotional Arguments

There is only so much that can be explained rationally. Many of our best impulses are led more by intuition than by an explicit mental process, and are only rationalized after the fact.

A discussion of emotional arguments should allow us to recognize our unconscious biases, and hopefully to offset them. These items are even more contentious than the rational ones, so do not expect any definitive answers here; at most, some uncomfortable questions.

The Joy of Building Things

In his excellent book The Existential Pleasures of Engineering, Florman argues that people build things just because they love to. He goes back to the wonderful Iliad searching for proofs:

Homer insists on telling us how each object is made. […] In more than 130 lines of poetry the fabrication and decoration of the fabulous shield is described. At other points in the story we are told in detail about the manufacture of Pandora’s bow, Hera’s chariot, Odysseus’ bed, and Achylles’ shelter.

This pleasure can still be felt in our veins each time we start a green field project: open a new blank document, initialize a git repo or just start sketching on a napkin in a coffee shop.

Over at the YouTube channel Primitive Technology, with almost 1.5 million subscribers, a mysterious Australian guy builds all kinds of things just using natural elements: baskets and stone hatchet, bow and arrow, or a complete hut. This last video has over 8 million visualizations; we can only presume that most of them do not come from survivalists intent on imitating him, but just people that watch his handicrafts out of pure pleasure.

But is our joy a valid argument to make a business decision? You tell me; in this day of difficult engineer retention, a worthy project can make the difference to keep the good people. On the other hand, if you want to start an online shop, building your own compiler may be hard to justify. So we must keep on looking for other reasons.

NIH Syndrome

The Not-Invented-Here Syndrome is the vilification of a tendency to distrust products offered by third parties.

There is a lively discussion at the c2.com wiki with pros and cons. Joel Spolsky, cofounder of Trello and Stack Overflow, summarizes it thus:

If it is a core business function – do it yourself, no matter what.

I worked for 6 years in the banking sector. At the time, most banks in Spain insisted on outsourcing their IT competencies, since they are not technology companies. But are they not? I contend that, in this day and age, banks are just purveyors of information: handling physical money is anecdotal and incidental to their business. Bank accounts and most financial products are just bits that move around. So, why should not banks embrace information technology?

Right now in the sector there is an opposite tendency to do IT in-house, and a good thing it is too. As FinTech becomes both a hot trend and a buzzword, it is becoming apparent that traditional banks can and should do more with technology, or they risk going the way of CD stores and Symbian phones. Time to market is starting to be critical even for mastodontic banks.

What constitutes a “core business function” is not so obvious. Is providing Internet connectivity a core function for Facebook? Are self-driving cars core for Google? Is Apple a watch company? What would you think if these companies outsourced those efforts?

Reinventing the Wheel

You are probably thinking that this way of reasoning leads straight to constant reinvention of basic tools.

Wheels come in many shapes and colors. Tesla gives the option of upgrading the model S with four 21’’ Arachnid Wheels priced at $7,600; for that money you can buy a small car. I cannot imagine that when their engineers set to build an outstanding set of wheels, their manager told them not to “reinvent the wheel”.

So reinventing the wheel is not a valid rational argument, although it may reach the pit of your stomach since it is a highly emotional subject.

Another popular formulation is: “does the world really need another testing library?”. The correct answer is of course: I do not know what the world needs, but if I ever need a new testing tool I will surely build it.

Learning the Easy Way

There is a reason why people that start programming write their very own implementation of “Hello, world”: to learn how things work. My favorite didactic tool is by far “learn by building”.

I have too often seen purported “DevOps engineers” which are just recycled sysadmins: they know how to install Jenkins or set up a Maven repository, they can hack up a few Bash scripts or even venture with some Python, but mostly they are unable to develop good, solid code. So I ask myself: where do they think that the “Dev” in “DevOps” comes from? For me, DevOps is about making your sysadmin infrastructure a first-class citizen, and treating it as one of your products.

If our infrastructure is itself going to be coded, and live in

repositories, then we need a little bit more dedication. That is what I

understand as “DevOps”. And as it happens, the best way to learn to do

this is to create the tools from scratch. Perhaps you do not need to

recreate everything for every project, but at least you should have done

it once. Otherwise, how can you know that a PHP script invoking

rsync can be as effective as a sophisticated Jenkins

pipeline?

And once you have learned how to do something, a nice bonus is that installing an external package is made easier: after all you know the mechanics pretty well. Sometimes, switching from custom code to external package is not a big deal.

Against Craftmanship

Too much craftmanship is not good either.

Artisans may get carried away and insist on doing everything themselves. Especially if they are good. But this is not always a good idea.

Like it or not, we are part of an industry and therefore must make good use of the huge number of parts available to us, 280k modules on npm alone at the time of writing. This will probably allow us to do more, be more productive and therefore feel better about our work.

Spitting libraries out there can be counter-productive, even more if they are not properly maintained. And there is no denying that maintaining software can be expensive.

A Most Welcome Third Way

Are we stuck in an endless loop of emotional arguments, with no rational way out? Maybe we can find a compromise between building a custom solution and deploying a third party product, and maybe we can even make it work.

Customizable Solutions

There is a middle ground between building a new product and just installing a third party tool.

SAP offers a complete solution for enterprise software, which is highly customizable – and in fact usually requires lots of adaptations before it is at all usable.

Open Source Software

Usually you can only extend commercial software in ways specified by the vendor. But with open source software you have access to the source code; you can extend it to do what you need.

Due to a long membership to the FSFE, and out of respect for the great Richard Stallman, I have long resisted using the term “open source”. But “free software” is still not accepted industry wide, and the English language still has this unfortunate conflation of “gratis” and “libre”. Furthermore, “open source” is more often associated with a community of developers improving the software.

Anyway, the idea is that once you modify the software you can send back your contributions. It even adds a certain kind of karma to your reputation, so everyone benefits.

I have received a number of contributions for my DevOps packages,

particularly for loadtest

which has already got 40

pull requests.

Remember our shiny new continuous deployment system built with StriderCD? We are planning on extending it for including a diff of the changes it has deployed in the notification email, and to send the contribution upstream so that everyone can use this new feature.

Joining the Pieces

Another very interesting use of customizable software is when several packages are combined to make a larger entity. This is particularly true for open source software, and most useful with DevOps, which regularly requires the collaboration of many moving parts.

Consider what continuous deployment requires:

- code repositories,

- a testing library + test suite,

- possibly some load tests as well,

- notification tools,

- and finally a deployment mechanism.

We mostly take all these pieces for granted, until they fail. A monolithic environment can provide for all of them, but you would be very lucky if all bits are ideally suited for your environment. Alternatively, each of these can be provided by different packages, which integrate together with some glue to provide the final platform.

In essence, sysadmins have long known how to make lots of pieces work together, particularly in Unix environments: having well-defined universal interfaces.

Conclusions

There is not a universal path that leads to all destinations. There is not even an optimal means of transportation for any distance. And there is not a single answer to this complex problem: build or not. Paraphrasing @msanjuan:

The answer to every interesting yes/no question is: “it depends”.

That said, there are many questions to consider that may help, among them:

- Are you building a state-of-the-art project?

- Which options is more cost-effective?

- Which option is more likely to succeed?

- What is the cost of switching?

- Which option is more fun?

Focusing solely on costs is not likely to be optimal. A tech company where nobody has fun is not likely to succeed in the long run: good engineers will burn faster, and probably move to greener pastures. But a company without profits will not last either. We should strive to reach a balance between having fun and making money. Ideally we should search for a path that takes both into account; the best path allows you to have fun and make money. Hard as it seems, that is why we are paid.

Acknowledgements

This article and the companion talk at DevOps Pro have benefited enormously from a presentation at Node.js Madrid (in Spanish). Special thanks to Fernando Sanz, Pablo Almunia, Javi Vélez and Alfredo Pérez for the stimulating discussions during and after the presentation.

Juan Carlos Delgado (llollo.com) first told me about StriderCD. Alfredo López Moltó (MediaSmart Mobile) has extensively reviewed this article. Any errors and omissions are of course my own.

References

Cyril Field: The story of the submarine from the earliest ages to the present day, 1908. A very interesting book about the history of submarines, although it thrashes Peral needlessly (and quite unfairly too).

John Allspaw, Jesse Robbins: Web Operations, 2010. An excellent introduction to some of the topics of what is now called DevOps.

S C Florman: “The Existential Pleasures of Engineering” 2nd Edition, 1996.

Published on 2016-05-26, last modified 2016-05-26. Comments, improvements?

Back to the index.