MoveinBlue, Five Years Later

Another Failed Entrepreneurship Story

Five years ago I was working as a project manager at ING Direct, a largish Spanish bank. In the worst of the mortgage crisis the bank decided to dispense with my services, and things were not looking good. This is the story of how I co-founded a company, did not get rich, and in the process got to be much happier.

Allow me to condense it in a few lessons along the way, and I promise I will try to avoid the common place.

Lessons will appear highlighted like this paragraph.

Contents

Breaking The Bank

When in 2007 I was hired at ING Direct as an analyst it felt as something of a success. Since 2005 I had worked as an external “consultant” for the banking sector in a few different projects. The financial sector in Spain has long employed these “consultants”, which are actually employees in disguise, to avoid bloating their workforce with lowly technicians. Now I held a technical position as a bank employee that was more or less like a group coordinator, for a team of varying size (from two to 15 developers).

A couple of years later I was told that I was now a project manager, so I finally needed not touch any code any more. This, needless to say, made me very unhappy. The Spanish IT sector has long clung to a fantasy hierarchy which was perhaps used at some mothball factory in the 60s, but which has nothing to do with the realities of software development. It goes like this:

- programmer,

- analyst-programmer,

- organic analyst,

- functional analyst,

- project manager,

- and finally manager, the top of the food chain, the leading light and aspiration of every lowly programmer.

Whatever “organic analysis” means outside of Chemistry is beyond me, despite having held the title for about six years; at one company it was comically shortened to “Anal. Organ.”, which might have been a Freudian slip but for their utter ignorance of the English language. Separating analysis from programming was always a bad idea, and these days it is suicide for any company that has any semblance of competition. However you will find that these absurd titles still infest job boards in Spain and elsewhere.

Around the time of my “promotion” the bank, in its infinite wisdom, decided to externalize all development work. There was no way to continue being an analyst since that position was being phased out. In retrospect, I could have realized at that point that my future would not be very bright, and look for greener pastures. But I plodded on as a project manager, juggling an ever increasing number of projects as the technical manager for financial cards.

In 2010 I was commended by the bosses after a very successful integration. My 2011 Q1 review was “good enough”; that was the literal result on a sliding scale from “bad” to “excellent”. But alas, at a large company you are never safe; if Zach Holman is not irreplaceable, who is? Certainly not me. I had never been able to keep my big mouth shut about things I did not like, and the boss of my boss did not appreciate it. Neither did her boss, or the boss above him, or the next boss. Oh, I had many bosses: the company was supposed to have a flat hierarchy, while in practice there were 8 steps in the ladder from the humble bottom feeder (me) up to the CEO. Not bad for a company with around 1000 employees.

Particularly I did not like the long hours, the long faces when I left for home after only 9 hours, the half-hour lunch breaks at my table eating a sandwich (in the vain hope of leaving earlier), the unpaid permanent on-call duty or the also unpaid visits to our offices to deploy a project at 4 AM. Having a two-year-old daughter somehow seemed more important than all that, and yet I could only see her during dinner and just before she went to bed (with luck; some days not even that). Esther, my partner and mother of our daughter, was also exhausted after working until lunchtime and then taking care of her all afternoon. Life kind of sucked, in the way only a first-world life can kind of suck.

In mid-2011 I had the gall of requesting reduced working hours, as was my right as the father of a child under 8. That same week I received a disastrous Q2 review by my direct boss. Right after that the head of IT and operations (six steps above myself) called me to his office and let me know that I no longer had a future at the bank. Parents with reduced working hours constitute a protected class in Spain, so they could not fire me directly. I negotiated a generous severance package (one year salary) and left the bank.

This happened in July 2011, almost exactly five years ago. At that point I had a little child, a mortgage and no job. But it tasted like freedom. Once again I could pursue a career as a software developer!

There was a serious problem, though. After four years at the bank, mostly dealing with obsolete technologies and managing projects, any development skills that I might have once possessed were blunt and rusty. Luckily I had run an interesting Python side project and had kept reading technical books. But still there was a significant gap with the state of the art. There is a lesson here, a perverse version of technical debt.

If you want to follow a career as a developer, your pay as a manager needs to compensate for the obsolescence that you are incurring.

I had to recycle myself to be a modern developer. Suddenly the severance package did not seem so generous.

Minding My Own Business

Around that time my good friend Diego Lafuente had told me about a little project of his: a travel startup he wanted to create together with a few of his colleagues at Fedit: Mauricio García Corredor and Íñigo Segura, with funding provided by Íñigo and by our business angel Juan Carlos Merino. After a few meetings they convinced me to join as CTO. Our mission: revolutionize how we all plan our holidays. Simple enough, right?

I conferred with Esther and told her that I really, really wanted to join MoveinBlue as the full-time, unpaid CTO. She handled it like a champion. The severance package provided for a nice cushion that bought me one year time to make it work. So I set to it.

The idea was to build a planner tool where users could plan tourist activities. With travel agencies and travel guides in decline, where will all those people learn what to do once they arrive to their destination? How will they find and book all the fun things they can do? We had the solution: build a holiday planner to find and track their activities. We had the silly idea that travelling once in a while meant we could enter this market confidently. We were wrong.

Knowing about travel does not mean you know about the business of travel. Or put another way, buying a product does not mean you know how to sell it.

This lesson actually comes from Diego, who spends at least a month every year travelling.

Full Steam Ahead

At its peak, MoveinBlue had more than 10 people employed full time, including five developers; most of them as remote freelancers. The stack was not revolutionary, but it was not bad either for its time: a single-page application and two mobile apps, all of them using a PHP backend. We successfully experimented with things like:

- an all-cloud solution with Amazon AWS;

- modern development practices, including having several test suites;

- continuous deployment, which has become a prerequisite for all my development work;

- and an all-remote team.

During my time as CTO at MoveinBlue I learned PHP and JavaScript, and soon afterwards I was working in our Android app. I was not earning any money, but my job ended up being quite valuable professionally. Here we can find a generalization of the first lesson.

Be sure to work in valuable stuff, or be sure to make enough money to compensate.

Although development work did not proceed as fast as we would have liked, things were running smoothly and we did not have stability issues. The trouble was elsewhere.

What Marketing Is About

Having never developed a product, I believed that “marketing” was synonymous with “advertising”. Nothing farther from the truth.

The closest we were to actual marketing at MoveinBlue was the bland segmentation we received from a consulting company that helped us define our product: both genders, aged 25 to 40, heavy Internet users, frequent travellers. No wonder, Sherlock!

Properly done marketing is something else. Our capitalist partner Merino is a successful businessman in several profitable ventures. He gave us a master class in early 2012: first you find a niche market where your product works, and where people is eager to give you money. Then you make yourself known in that market, get people there to use your product, and then convince them to give you money. If necessary, you tailor your product to that particular set of users until they are happy. Then you find another niche market and repeat.

But alas, his advice came too late. Actually we tried to contact some niche markets that might have found our planner useful: divers, conference organizers, or bikers. With zero success. So we continued building our product for an imaginary market, thinking that eventually users would come pouring in. We never cared about earning our first €10, which is now a widely known error. Diego summarized it thusly.

Focus on earning your first €10, instead of just increasing your user base blindly.

The urge to get users quickly has worked for some high-profile cases, but it is not how most companies make their money.

Bad Business

This brings us to the second broken leg of our strategy.

US entrepreneurship lore states that successful startups need both an inventor and a businessman: Hewlett and Packard, Wozniak and Jobs, Gates and Allen. In our case the four founders were engineers, either by training or by trade. Too much engineering and too little business: we were all very busy creating a product and building a platform. Everyone was worrying about the functionality and the design of our website, and not with actually selling anything to anybody. Despite the occasional advice of Merino, nobody was minding the business. Diego lent me another lesson here.

Good technology does not a good product make. If your product does not serve the needs of its intended users, what technologies it employs will not matter.

One thing we did right was keeping tabs on the competition. Yes, even in the niche non-existing market of holiday planners there was competition, and plenty of it. We kept track of ten or twenty different companies at any given time. Just as if I needed convincing for the next lesson.

Ideas are not worth a dime without great execution.

There is a commonplace version which says that “ideas are worthless”, nicely debunked in Ideas aren’t worthless. But what I know for sure is that many people can come up with the same idea, be it good or bad. Several groups around the globe had the same idea as we did, and a few of them built products very similar to ours. Some even got millions of dollars of financing, whereas we had some pocket money and much enthusiasm. But none succeeded at the holiday planner. I am not sure why; maybe people dislike planning their holidays after all. But other approaches have failed as well.

To this day there is a huge untapped market waiting for the picking: tourist activities are a disorganized mess which lives for the most part offline, and which would benefit greatly from a broker that helped small providers sell to strangers. But nobody has cracked this golden nut yet.

Update: in September 2016 Airbnb bought Trip4real for an undisclosed sum, reportedly between 5 and 10 million euros. The business model is not too dissimilar from ours but with activities provided by individuals instead of businesses. With only 40 thousand users and three thousand “experiences”, it goes to show that there is money in the sector.

A Good Ride

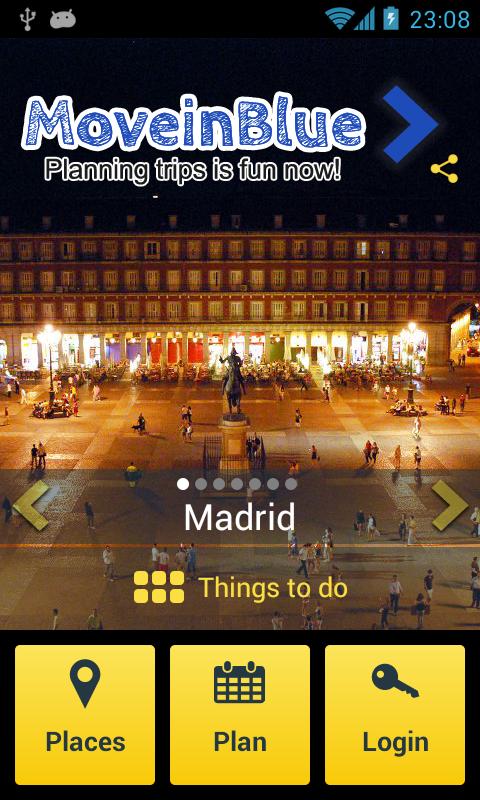

During the first half of 2012 we were busy writing and releasing our mobile apps, which again failed to revolutionize the way we travel. We had an external company to help me build the Android version, and Diego with the iOS port. They were nicely done but were not widely used.

At some point in the summer of 2012 we ceased operations. There have been many studies about the reasons for startup failures. Do not be fooled though. I read this great truth somewhere but cannot find the source right now.

The main cause of startup failure is that the team simply gets bored of trying to make it work.

And so it was in our case.

I still think that, had we continued working in our product design, we might have eventually gained traction. After all we did a couple of iterations on the website, and our final design was miles ahead of our first try. But sadly we did not have the resources to iterate our mobile apps, which are a natural fit for a holiday planner: how many of you take your laptops to your holidays? Well, you should not! Holidays are for browsing lazily from your phone, and laptops feel too much like work.

Since then Íñigo has tried several times to pivot and make our little venture work out of his own pocket. He has even sold actual travel activities, but has also failed to gain enough traction. In the next few months we are ceasing operations completely.

Founding Or Funding

When I tell people about the fate of our little company, many are relieved to learn (in typical Spanish fashion) that I had invested “only time”, and not fronted any money. How they think that money is more important than time is beyond me.

A year of your limited time on Earth is worth more than any money.

Unless of course you end heavily in debt and having to repay it for several years, in which case you are again wasting huge amounts of your life.

Meeting People

I have mentioned that we worked with several freelancers and a few companies, and many of them are great professionals that I remember fondly.

- Jesús Díaz did a splendid job with us several months.

- Edoardo Batini worked for us less time but just as intensely.

- Juan Searle and Jonathan Martín helped us build a kick-ass website.

- César Domínguez worked with us on two really cool Android and iOS apps.

I had very interesting conversations with all of them. A big part of my freelancing work has been done for people I met while at MoveinBlue, quite often working for people I had previously hired.

Working at a company makes you money, but being an entrepreneur allows you to meet interesting people. Interesting work often comes from interesting people you know.

Freelancing

After we gave up on MoveinBlue I sent my CV to a few big companies like Amazon or Google, and was promptly ignored. I have to recognize that I felt something akin to a vindication when I was recently contacted by Amazon to join their new Madrid dev center. Right now I am not interested in a job change (my standard response for recruiters), but it is nice to know that my skills are appreciated. Not so at the time.

So I started interviewing for a few startups and consulting companies. I actually got two job offers, but ultimately both involved working at a bank as consultant, which felt like a step back. Again I conferred with Esther and told her that I was not interested in those jobs. She encouraged me to wait for something better, since we were not yet (too) pressed for money. That is exactly what I did.

Diego and myself started freelancing for Kimia, a marketing company, doing web and mobile development. Reprising our roles in MoveinBlue, I wrote an Android SDK while Diego did the iOS port. Due to our limited experience we had to charge them a pitiful fee of €25/hour each.

This lasted for only two months. Our client was quite satisfied with our job, but we could not take another project. Diego soon found a job at Tui Travel, where his experience at MoveinBlue was quite valuable.

I have never stopped doing freelance work. When I (spoiler alert) signed a full-time contract a few months later we agreed that I could do work on the side. As I do not depend on it, I can pick interesting projects. Also, I now charge a fee of at least €80/hour, which is not bad for Spain.

High Scalability

As an avid reader of High Scalability, I yearned to work at a company that actually had something to scale.

In September 2012 I attended DeNormalised NoSQL, organized by the excellent skills matter, out of my own pocket. Many speakers told us how they used NoSQL databases to serve an ever-increasing number of requests per second. Theo Hultberg explained how his organization processed 25 thousand requests per second, or 25 krps. Then Malcolm Box told us how his tiny company had won the contract for the UK version of the X Factor, where users had to vote using their mobile phones for their favorite artist. During a two-hour window every week they had to deal with peaks of 50 krps, and then take down all servers again; this would not have been possible without Amazon AWS. The venue came down in applause. I was hooked.

Around that time I had started using Node.js for a side project, and it was lots of fun. Soon after my stint doing mobile apps at Kimia I was peddling my freelance business for Node.js, and was being relentlessly turned down. Then I went to an interview at MediaSmart Mobile with the same intention; surprisingly I was offered a full-time job. The company was using Node.js to process an astounding 2 krps! And thus I joined the company in January 2013.

Since then we have doubled our revenue every year. We are receiving peaks of 325 krps, process a total of 25 billion requests per day, and serve more than 30 million daily impressions.

Before MoveinBlue I was mildly allergic to JavaScript. After using jQuery to build our website I realized there was something to this strange little language, and with time I have come to appreciate it. In March 2013 I gave a talk at MadridJS which was attended heavily. A few years later I am the organizer of both MadridJS and Node.js Madrid, have helped organize two editions of JSDay, have got to teach JavaScript at a bootcamp, have given talks in a few countries, and have got to meet many interesting people in the JavaScript community.

This year I had the privilege of giving a talk at FullStack London, also organized by skills matter, where I told the audience how we have scaled up to 325 krps, using Node.js for a lot of DevOps tasks. We have written critical parts of our infrastructure in Erlang and Go, and had a blast while scaling our servers. It provides for a nice closure to my little tale.

Conclusion

I learned a lot during our run at MoveinBlue. I wanted to tell the story as I remember it, before I forget it any further.

Recently I deleted my LinkedIn account, tired of continuous spam and (let us say it this way) their careless handling of passwords. Let this article serve as a CV of sorts for this stage of my career as an entrepreneur.

As to the other co-founders, they have also been influenced heavily by our experience. Nowadays Diego works for Hotelbeds, where he actually sells to travellers. Mauricio joined Opinno, a company focused on innovation. He has still not shaken the entrepreneurship bug, and will soon start a new venture. Íñigo is still involved in the development and commercialization of new technologies and high-tech products.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my three co-founders Íñigo, Mauricio and Diego for reading a draft of this document and making many valuable suggestions. Three of the lessons come straight from Diego (they are easy to recognize as they are the best three, but I will let you guess which).

Thanks also to Jesús, César, Juan, Jonathan and Edoardo for their nice comments.

Published on 2016-07-27, last edited on 2016-09-25. Comments, improvements?

Back to the index.