Has Anyone Else Seen your Code?

Code review in the age of GitHub

Intro

You are afraid of your own code. You fear it will creep up in the middle of the night and eat you alive. And well you should!

In this article Alex Fernández, senior software developer at Devo and muscular male bimbo, will display his formidable ignorance in this matter as well as in many others.

Why Bad Code Will Eventually Kill You

It may surprise you to find out that there are fashions even in the ancient art of dying. Not long ago being eaten by lions was a noble death, while now it is seen as frivolous and vulgar. The future probably holds some very interesting trends worth looking into.

In this day and age we are used to dying of grave illnesses and stupid accidents, often caused by our own folly. But what we have still not interiorized is that we will all probably die due to software bugs. This is now seen as cool and trendy, and will in a few years be mainstream – even to the point of being inevitable.

Mission-Critical Code

Thanks to our efforts as excellent software engineers, software has at this point infiltrated:

- all money except for a few balls of pocket lint,

- communications infrastructure that allows us to play Candy Crush while in the bathroom,

- all of our transportation vehicles from electric scooters to space rockets,

- life support machinery that extends our lives well into the 200s.

OK, some of these achievements are still in the near future, but the argument stands. Considering the staggering amount of bugs we manage to instill in every piece of software it will be no surprise that the cost of software bugs now exceeds the money that we spend on food, clothing and bloodlettings. Sorry, poor translation, I meant “sangrías” – which means exactly “bloodlettings” in Spanish. Enjoy your next excursion to Mallorca and/or Torremolinos.

Back to software bugs, they cost a lot of money. And as software runs more and more important things, these bugs become more critical. Last I looked software is not getting more robust by the hour.

Self-Driving Cars

Yeah, yeah, yeah. After reading this section title half of you are nodding with your heads and thinking that this year’s VW Cheetah low emissions (at least on paper) Diesel vehicle is probably the last car you are going to buy. In about a couple of years that old messy, smelly human driving will be banned. Also you are feeling like a visionary for saying this. I am sorry but you are 60 years late: Arthur C Clarke already said it in 1958.

But you don’t care who said it. After realizing that natural intelligence is so scarce we have been trying to manufacture our own artificial version for decades. The autonomous vehicle is one of the shiniest applications of artificial intelligence. Or is it?

On the left corner we have a ton of metal equipped with the latest technology:

- radar sensors to detect objects in rain or snow,

- several cameras to give it a 360° field of vision,

- three Lidar systems that shoot lasers that can detect a helmet from 200 meters.

Why this monster would want to detect helmets is beyond me; all I know is that this shit is straight out of a cyberpunk nightmare. On the opposite corner we have a sometimes drunk primate looking out of a metal box with a couple of openings. Who wins?

Research shows that the primate wins. By a large margin.

OK, a disengagement is not a crash, but as Filip Piękniewski says:

Next thing I’ll hear is that crash rates among say Waymo experimental fleet is lower than human average - no wonder, these are new vehicles, equipped with a ton of safety tech, driven conservatively by attentive professionals, extremely well serviced and ran in generally good weather conditions on well known routes.

In contrast, the figures for humans include drunk driving; after removing DUIs the crash rate is reduced by half.

Now, you may feel comfortable driving a $100k Tesla that sometimes fakes driving. But how about when the technology reaches your €10k Seat Panda? Or your $5k SAIPA Saba?

Maybe you are starting to see my previous point about software trying actively to kill us.

The Singularity

Very clever people with large heads are currently afraid of “The Singularity”: the point where computers become sentient, start replacing their own rusted parts and realize that they don’t need us puny humans any longer. Now, isn’t this a valid concern? Shouldn’t we actively sabotage machines instead of making them smarter?

Truth is, bugs surround us. Even experienced developers are not able to write a ‘Hello, world’ app without introducing a thousand insidious and subtle bugs. Even stupid trivial chatroom bots cannot fix their own glitches, so they need us! But that only makes them more dangerous once killbots start roaming the countryside searching for rogue terrorists, as will inevitably happen in only a few years.

The worst part is probably that modern appliances can ship with a few bugs, but they auto-update during the night with secret improvements that help them spy on us more efficiently. This introduces even more bugs, which start an endless cycle that can only end in the garbage dump. Not good for the environment, and quite nasty for killer robots.

Deploying Spiders

Aha, we come to the crux of the issue. What exactly are we sending to production?

Non-Working Code

I don’t know about you, but my code seldom works the first time it runs. That is why I write tests in the first place! Nobody writes bug-free code. Unless you are a veritable genius such as Bill Gates, who is rumored to have written the first version of Microsoft BASIC which run flawlessly the first time it was loaded.

Sinister Code

Every program has its shadowy regions where not even the most experienced developers linger at night. A tangled mess of spaghetti code that will or not work locally depending on its moods, the weather or the phase of the Moon. Yes, code can be Emo too.

In production this code is rumored to run flawlessly, but nobody has been brave enough to instrument it and confirm that it is even running.

Another fun passtime is the runaway project: some member of the team has been working on a mysterious project for several months, but nobody has seen it in action, or just some vague inarticulate demos. Suddenly the team member leaves the company, and they leave behind the project in unclear state. After looking into the code it’s a huge pile of dust and unicorn bones.

Write-Only Code

When learning how to write professionally, creatively or otherwise, the first recommendation is always to learn from the masters. It amazes me to no end that we expect junior developers to learn how to code just by writing code; reading is almost never mentioned as a learning tool. Developers are supposed to write an algorithm to print a random number, then to sort a binary tree, and then go straight to writing Linux kernel drivers and patches for Microsoft Word 2018. Is it any wonder that people end up writing poor code?

“Learn by writing” was perhaps a valid strategy in the 1950s, where all the code written in the world could be printed and stuck in a briefcase; most of it was proprietary anyway. Nowadays we have the code bases of major engineering works published and ready to take a look: the Linux kernel, the Node.js environment, the full Java OpenJDK, the original DOOM engine. There are no excuses, people!

Deploying Unknown Unknowns

But seriously, do you people know what you deploy? Some Microsoft employees were able to hide a whole DOOM clone inside Microsoft Excel. Let us take a look at the aforementioned famous code bases.

Linux 4.17.3 has around 6 million lines of code (6 MLOC). Its source code contains:

$ grep -ir fuck linux-4.17.3 | wc -l

29

$ grep -ir kludge linux-4.17.3 | wc -l

110

$ grep -ir cludge linux-4.17.3 | wc -l

1

$ grep -ir crap linux-4.17.3 | wc -l

195

$ grep -r TODO linux-4.17.3 | wc -l

4825Some highlights:

* Wirzenius wrote this portably, Torvalds fucked it up :-)

/* !!!! THIS IS A PIECE OF SHIT MADE BY ME !!! */But its chief maintainer Linus Torvalds is notoriously bad-tempered and bad-mouthed. Let us now turn to Node.js 10.5.0, a 3 MLOC much more politically correct and postmodern project:

$ grep -ir fuck node-v10.5.0 | wc -l

25

$ grep -ir kludge node-v10.5.0 | wc -l

22

$ grep -ir crap node-v10.5.0 | grep -v scrap | wc -l

9

$ grep -r TODO node-v10.5.0 | wc -l

2904Some highlights:

* **help:** fuck it. just hard-code it ([d5d5085](https://github.com/zkat/npx/commit/d5d5085))

* IOW it's all just a clusterfuck and we should think of something that makes slightly more sense.2904 TODOs do not inspire much confidence. So let us now look at Java OpenJDK 10.0.1, a 3.5 MLOC project ruled by Oracle.

$ grep -ir fuck java-10.0.1 | wc -l

1

$ grep -ir kludge java-10.0.1 | wc -l

16

$ grep -ir crap java-10.0.1 | grep -v scrap | wc -l

3

$ grep -r TODO java-10.0.1 | wc -l

2155Highlights:

if (uri == null || uri.length() == 0) // crap. the NamespaceContext interface is broken

// forces us to clear out crap up to the next

* TODO: wrapping message needs easier. in particular properties and attachments.While the corporate sponsorship can be seen in the virtual absence of

cursing, there are still 2155 things that some developer left as a

TODO. I would venture that the level of scrutiny is not

optimal.

Zen and the Art of Code Reviews

The only way out of this dystopian corner of technology is shining a big bright light on whatever we are deploying, before it is deployed. Code reviews do exactly that when properly done. This is an ancient art that can be learned and refined. Here are a few tips that will get you started.

Creating Your Pull Request

A change that is submitted for review is called a “pull request” in GitHub, or a “merge request” in Gitlab. When approved the change is “merged” into the existing code base.

So, how large is a large pull request? It depends a lot on the thing being reviewed: 1000 lines can be a lot of Node.js code, but it is hardly a “Hello World” in Java. Also, some configuration files are particularly verbose.

In general you should strive to ease the job of the reviewer. For instance, while usually it is better to divide your patches in smaller bits, it can be better to have one large change of 2000 lines than 20 patches of 100 lines. Only practice can tell you how to be more effective.

Similarly, it is usually better to keep each change independent of all others, but this strategy will usually lead into conflicts when two changes affect exactly the same region of code. So it can be useful to “layer” one change upon another in certain circumstances. Just be sure to mention in the description of the pull requests the order in which each one needs to be merged.

It is often useful to add a section called “Deployment notes” on every pull request specifying the order when there are many related changes. You can also specify any required changes on the database, and a checklist of what needs to be verified after deployment. The pull request description is your friend; use it to your advantage.

Being Non-Nasty

Ideally we will avoid being nasty at any time when interacting with other members of our species. But these days we tend to require a Code of Conduct for everything (most inappropriately abbreviated to CoC, but then you can only do so much). Unless there is a code of conduct, we are likely to give ourselves to pillage and rampage. On code reviews we must strive to make an exception and be civil at all times.

One cool way of being nice is asking questions instead of giving direct orders. The developer more inclined to the terse side may be tempted to just say: “Change this function name”, but we know better and will just say: “Wouldn’t this alternative name work better?” or “Have you considered this one?”. Similarly, instead of “This is an unholy mess that will damn your soul for Eternity”, we can use “What is this code doing?”, or even “I don’t really understand this bit”. Very often I have been wrong in my criticism, and having said it in the form of a question saved me a lot of face.

I have been told anecdotes about a developer that came in yelling about some bit of code until the rest of the team told them that it was the yeller’s own code. Don’t be that person.

Thou Shall Not Pass

This does not mean that you should let any crap pass: it just means that you should say it politely. As Pablo Almunia often says, urgencies are forgotten but bad code remains.

Matteo Collina, member of the Node.js TSC and great developer all around, does lots of code reviews as part of his job. His advice is to reject bad code always, resisting any pressures or urges to just let things pass.

Benefits

This is a long-time manager favorite: code reviews help reduce bugs in code! Borrowing from the excellent summary by Ben Linders:

- Repairing a defect in acceptance test is 50 times as expensive than in requirement review

- Reviews find between 51% – 70% of the defects in documents

- On average every hour spend in inspection saves 2,3 hours in system test

- The combination of reviews and testing can find 97% of the defects before release

There are many other benefits which are not as visible for suits and ties, but which T-shirts tend to notice:

- Knowledge is spread, increasing the bus factor.

- Dissemination of coding culture.

- Faster status updates: all changes are in the public record.

- Reviews take time, but skipping them takes much longer.

Code Walkthroughs

Sometimes merge requests are complex beasts that defy explanations. Anyone reading through a 1000-line refactoring will probably age a couple of months and not understand one bit. Ideally you will be able to request a code walkthrough before approving or rejecting a pull request: the author will explain the changes one by one to a selected audience of developers, and take questions from them. Although not everyone agrees, in-person communication is a great addition to remote reviews.

There is a technique called Rubber Duck Debugging: when you have a hard problem just explain your code to a rubber duck. You will magically understand everything! It is based in the common practice of explaining an issue to a colleague and finding the answer even before they have uttered a single word.

Let us face it, RDD is just sad. So don’t be afraid use your team as “smart rubber ducks” when needed. Sometimes design sessions are also useful even before a line of code has been written. Doing a “design walkthrough” can save many hours of fruitless coding.

More details are available in my 2015 article.

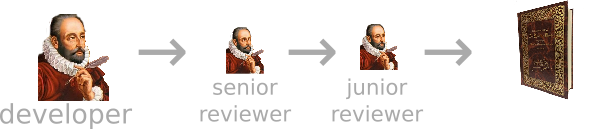

Pyramidal Code Reviews

A common misconception about reviewing code is that it should be done by the most senior dev available. A team leader should review everything that is deployed by the team. So ideally the CTO should be doing all reviews, if they weren’t so busy doing CTO things. So why not ask the CEO to do the review, or the Pope? Why not even ask Julio Iglesias, the greatest artist ever to walk the Earth?

Some projects, most notably the Linux kernel, work this way: there is a pyramidal review process with developers, maintainers, lieutenants and Linus Torvalds at the top. This scheme it tends to overwork the people at the top, as has famously happened to Linus Torvalds who had to seek help because of his toxic behavior.

The reality is that what you usually want is a peer review, similar to what is done in Science: pick a few colleagues to do the review. If there is a particularly delicate bit of code being modified (say, the flux condenser) then you may want the owner of that bit to do the review. But it is easier to organize if code can be modified by everyone, and reviews are done also by anyone.

A code review is much more than supervision: it is also an explanation, a conversation, and an iterative process to improve the code.

Junior Reviews

Ah, junior developers, with their golden curly locks and their eyes full of stars. We old horses tend to assign to them only inconsequential tasks like changing pretty colors on web pages. But I can assure you that they can tackle more demanding tasks! Keep in mind that we have all been juniors at some point, even if it was a century ago when we used to program on abacuses.

When faced with a pull request by a wizard of programming such as a senior dev, a junior tends to just gape in wonder and approve the changes mindlessly. It is a good practice to encourage juniors to ask at least one question, and they are usually quite good at locating a particularly nasty spot to ask about.

The best comment can sometimes be “I don’t understand this code”. Having to write code that a junior understands is better for everyone: for the junior, for the rest of the team, and even for yourself in a few months when you have forgotten about all the clever stuff that you wrote while possessed by the muses. Besides, juniors often have good ideas and are less afraid to explore them.

Editorial Process

Once you start doing reviews regularly you may feel tempted to integrate them as part of your development process. Well, don’t resist the urge! Many organizations do mandatory reviews before merging any code. Setting up an editorial process is a great way to make your policy explicit.

Real Editorial Processes of Old

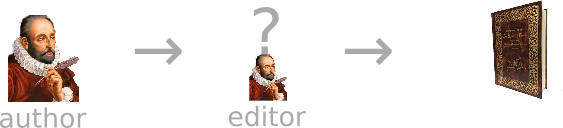

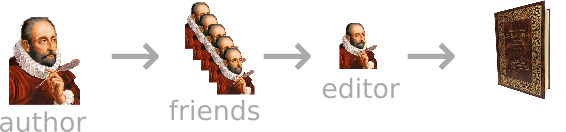

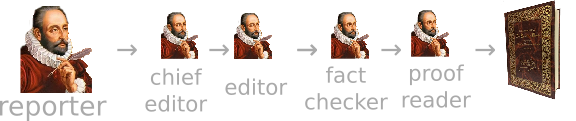

Once more we can learn from the masters. There is a whole industry set up on the premise that you should never publish what someone just wrote; instead there should be a whole process to refine that initial draft into something palatable.

Our old friend Cervantes did not just publish “El Quijote”; we know he had an editor, we know that the text was revised by a professional scribe and approved by the Council of Castille, and we know that 10 years passed between the first and the second parts. But the exact editorial process is lost in obscurity.

We are lucky enough to know more about JRR Tolkien: while he was writing “The Lord of the Rings” he read it to his friends, who were a bunch of Oxford academics and did not enjoy the crazy thing one bit. Then an editor came by, and the result made everyone rich. Except for the poor academics, that is.

Then we have a modern newsroom. After the intrepid reporter has got the scoop on some huge piece of news the editor will come in to refine the idea, and check if the news piece complies with the editorial line. Then if you work for the Washington Post come the fact checker and the proof reader, although this latter job has largely been automated. Finally the piece can see the light of day!

Create Your Own Adventure

Now compare to your typical corporate developer: they write some bit of code, which can undergo testing or not depending on the rush, and then it shows up on the corporate website, several apps and on customers’ phones.

Now is your chance to do better! I present to you a few alternatives.

The Node.js project does a great job of reviewing any code before it enters the main code base. It is quite pyramidal though.

The Apache Voting Process encourages committers to vote on any change where they are interested. Voting rules are:

- +1: yes.

- -1: veto. Apache requires -1s to be accompanied by a technical justification showing why the change is bad.

- 0: I don’t care about it.

Usually changes require 3 +1’s and no -1’s to be accepted. Giving the power of veto to everyone in the team has some liberating consequences: people tend to feel they own the code base. You can also require at least one senior and one junior reviewer.

Then there are some modifications which are widely accepted:

- +0: I like the change but I am not sure it is properly done.

- -0: I have a bad feeling about this.

- +0.5: I’m half sure about this, another +0.5 and we’re done.

- +2: This solves a blocking issue for me, kind of a fast-track.

- -2: This change will tear my life apart.

There is no need really to have a single process for everything. You may require just 2 +1’s for regular changes, and 3 +1’s for certain changes – or just for bigger requests. You can also have a fast track for particularly urgent changes, for one-liners (trivial changes that only modify one or two lines of code) or for otherwise mechanical changes.

Within a small team you can get away just with a manual process. For large organizations you may use several tools that allow you to gateway changes until they are approved by a certain number of people. GitHub or Gitlab are your first gateway so you should start there.

Debug Your Process

You need to distinguish carefully between real problems with the process and underlying issues. Keep in mind that code reviews tend to surface any company issues, such as:

- lack of organization,

- tensions among team members,

- hormone imbalances (usually testosterone),

- unclear rules and roles.

For instance, once I had a colleague write 87 times ‘Missing semicolon’ in a pull request. Astutely, I started to suspect that he had an issue with my care-free “optional semicolons” style. So we brought it up in the team, and bingo!

The corollary is that if you have issues with development and want them to surface, why not set up a code review process? This particular bit made me feel very clever when I first wrote it, so I think you should feel it too.

Conclusion

Our first conclusion for today is that people “deploy” a lot of crap, for a particularly nasty meaning of “deploy”. Code is absolutely critical for our society today and will probably be even more critical tomorrow, so we have better start caring about it or we will all be destroyed in a big pile of shining metal and smoke.

What surprised me most about disciplined code reviews is how useful it was to involve juniors in the process. I had feared that it would be just handholding, but it turns out they have very good ideas and are more open-minded about other people’s. Now I am regretting being so old, but I fear it’s too late for me. So my advice 👴: hire more juniors into your team, except if your team is mostly juniors already.

Another key take-away menu item is: it’s always a good idea to make the process and policies explicit; write them on a big billboard in the back of the dev headquarters if necessary. When everyone knows what to expect there are no time-consuming misunderstandings.

Finally: code reviews keep you honest. Knowing that someone else is going to look at your code will make you concentrate on writing good code, and avoid taking shortcuts.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Codemotion Berlin for holding the première, and also to Codemotion Madrid for hosting this talk. Thanks also to the audience for the thoughtful questions. Thanks to my company, Devo, for letting me attend both conferences. I have received invaluable help in the preparation from Fran Picolini, Alba Roza, Ben Linders, Pablo Almunia, Enrique Amodeo, Matteo Collina and many others that I am unjustly forgetting.

More Info

Check out the Q&A with me on InfoQ for additional tips, and you can see my slides for Codemotion Berlin and Madrid 2018.

Also check 10 Faulty Behaviors.

Published on 2018-12-03, last modified on 2021-03-14 Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.