More Adventures in the Land of Go

Large Projects

A couple of years I had the chance to play with Go (or “Golang” as exasperated people searching on the web often use) and wrote part 1 of this article. In the last few weeks I have delved deeper into the gopher hole and have been discouraged from using it on large projects. This longish rant explains why.

I will center on largish projects while trying to avoid well-trodden ground such as the lack of generics. I still think Go is a good option for small trivial projects when Node.js does not deliver the required performance, such as intensive computations or simple load tests.

More Language Fun

Criticizing those aspects of a programming language that we don’t like is an endless source of amusement.

Pointless Pointers

After using C for any length of time pointers become a constant annoyance. One of the cool innovations in Java was to pass all objects by reference so there was no need to use pointers explicitly any longer.

But alas, Go was masterminded by a member of the original Unix team.

So suppose that you are writing a struct with a setter

function:

type Box struct {

Width int

}

func (box Box) SetWidth(width int) {

box.Width = width

}

func main() {

box := Box{5}

box.SetWidth(10)

log.Printf("Box width is now %v", coolBox.Width)

}We create a box with width 5, and then set its width to 10. What do you think will be the result? Expert Gophers are probably cringing in their chairs. The rest of us probably guessed “10” which is of course wrong. Box width is still 5! You can check it for yourself.

What kind of evil witchcraft is this? To get the desired behaviour you need to use our new improved cool box:

type CoolBox struct {

Width int

}

func (box *CoolBox) SetWidth(width int) {

box.Width = width

}

func main() {

coolBox := CoolBox{5}

coolBox.SetWidth(10)

log.Printf("Cool box width is now %v", coolBox.Width)

}This time we get 10 as expected.

Can you tell the difference? Methods in Go can be declared on a struct, thus:

func (box Box) SetWidth([...])in which case they operate on a copy of the original struct.

Every invocation results in a new Box. Why this is ever

needed on this world, I don’t really know.

Methods can also be declared on a pointer to the struct:

func (box *Box) SetWidth([...])That small asterisk makes all the difference. Now the method operates

on the original struct and can thus modify it. Adding to the confusion,

access to an attribute is done using the dot ‘.’ for both

structs and struct pointers.

The problem is just as confusing for regular functions. At a certain point you realize that passing variables around by value is probably not what you want: whenever you are tempted to modify a value you will get a surprise:

func enlargeBox(box Box) {

box.Width += 5

}

func main() {

box := Box{5}

enlargeBox(box)

log.Printf("Box width is now %v", box.Width)

}Width is of course still 5, since enlargeBox() has

operated on a copy of the original box (play). When this is

done five function calls in for a variety of parameter objects it is not

easy to see the problem.

Regular struct access is also slower since you are making copies of

structs all the time and can clog the garbage collector in high

performance applications. So you start using pointers for everything.

Any parameter you see without the dreaded * becomes a

pending optimization. But this can be a trap! Pointers to

interfaces are no good as parameters and for some reason

you need to pass the interface without *. Unless you know

by heart which of your objects are interfaces and which are structs you

have to add * everywhere and wait for the compiler to

complain.

Once you are using pointers consistently, you start getting these fun errors:

panic: runtime error: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereferencewhich are equivalent to the infamous Null Pointer Exception in Java,

or the ReferenceError in JavaScript. And that is how

pointer safety is compromised.

Granted, Go at least has no pointer

arithmetic, but that is a meager consolation when you have to add

* and & everywhere. And don’t even get me

started on passing slices around, or you may end up with abominations

such as *[]*[]*Box: a pointer to a slice of pointers to

slices of pointers to Boxes.

This for me was the dealbreaker. But there’s more.

Minor Nitpicks

Even the most unimportant things can add up. Right now it’s all coming through in waves.

As has been said

before, implicit

interfaces are a mess. Not every class that implements the method

Start() and Stop() is a Server:

it can be a VideoPlayer or a Car in a game.

Declaring interface pertenence explicitly communicates an intent: this

class does this and behaves like that. But in Go you can never trust

that the class that acts like a Server didn’t start its

life as a VideoPlayer or a Car.

Go uses capitals Every Darned Where. Public attributes and methods in a struct are written using uppercase while private stuff uses lowercase. This looks like a nice convention, but it can force you to write capitals more often than you might like.

It is easier to write private resources with an underscore

_ prefix as in JavaScript. Making the default behaviour

public is more comfy, although this point is highly debatable as has

been pointed

out by SamuelAFalvoII. To be honest I also dislike the underscore

_ prefix; I prefer to export just the relevant methods and

attributes. But I digress; the nitpick is about having to write so many

capitals.

The copy() built-in also makes a weird choice. While the

world slowly converges to a single, logical version of copy that goes in

my mind as “copy from source to destination”:

copy(source, destination)Go programmers have stuck with the older C-like version:

copy(dst, src)This breaks my mind in surprisingly aberrant ways. Never mind the

obnoxious abbreviations dst and src.

Go authors encourage the use of single name variables whenever possible. I believe this encourages newbies to use the language, specifically two-finger typers.

For everyone else single-letter variables can quickly become a mess. Good code is written once and read many times. It is true that short variables are often fine, but making it the default is, should I say, dangerous. Apparently we have learned nothing from the whole fiasco of cryptic Unix commands, which at least was somehow justified by the scarcity of bytes at the time.

Packaging Your Code

Another source of frustration is the poor support for packaging. The

gold standard for me is Node.js and its npm which not

surprisingly boasts more modules than any other package manager.

Package Layout

There seems to be no official layout for a package. The documentation shows a somewhat messy layout. There is support for subpackages but no standard paths: in most packages code just lies around in the root directory of the package.

Big projects usually have many folders; apparently sub-sub-subpackages are the only way to go. This contrasts with Node.js where a single export point can easily be specified, while maintaining a complex internal structure.

Even inside a subpackage there is no hint of structure: everything is

piled up in files with random names. There is no way to know which

structs or variables are defined in which files, since they are exported

whenever they use capitals. The only rule is that test files end with

_test.go, and I happen to dislike separating tests from

code. ಠ_ಠ

Package Manager, or Lack Thereof

9 years after its creation and 6 years after its 1.0 release Go still has no official package manager. dep is labeled as an “official experiment”. Contrast this with Node.js: released around the same time as Go it got npm a few months later.

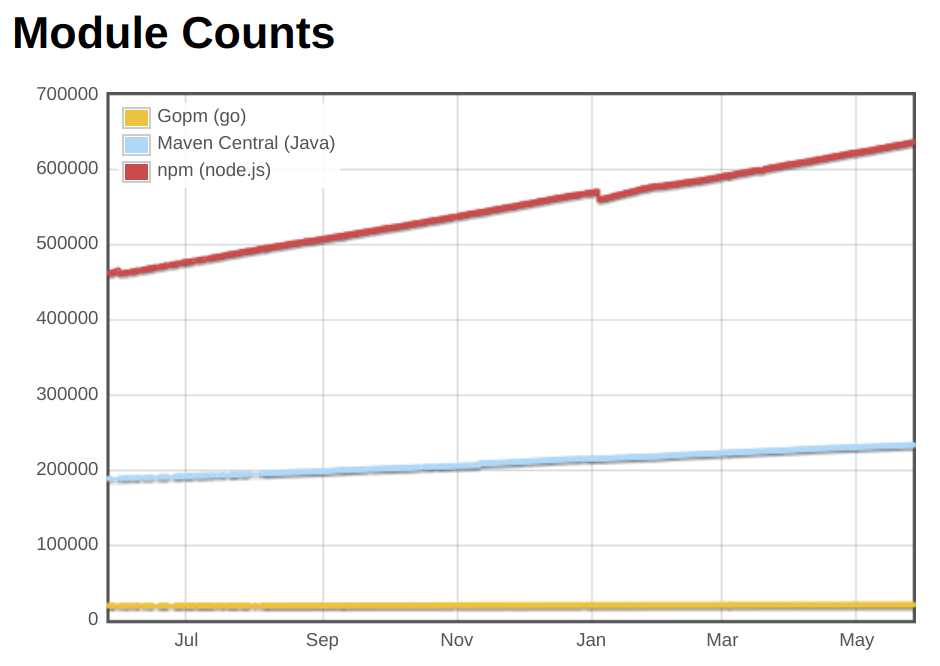

There are other Go package managers; the most popular seems to be gopm which counts more than 20k packages. Unsurprisingly not many people use it: golang.org/x/net is the package most downloaded ever, with about 13k downloads. These 20k packages are dwarved by the 200k in Java’s Maven and the 600k for JavaScript’s npm.

All kinds of poor excuses can be given, from the bad average quality in npm to the nature of Go as a “systems language”. In reality Go is often used as a web development language, it just lacks the libraries.

Accessing Other Packages

The official way of downloading other packages is therefore to

go get them:

go get github.org/golang/lintThis downloads the package lint from the

golang account on GitHub, and stores it in the

$GOPATH. There is no way that I have found to specify a

certain version: the latest version is always used. Not a good

perspective for stability with multiple dependencies on third party

packages; this may not seem like a good practice anyway, but is

routinely achieved routinely with npm or Java’s Maven.

Single Workspace

While we are at it, where should we keep our code locally? Again, the docs have this to say:

Go programmers typically keep all their Go code in a single workspace. […] Note that this differs from other programming environments in which every project has a separate workspace and workspaces are closely tied to version control repositories.

Keeping all code together is a poor practice. Maybe you work for

different companies and want to keep their code separate? Maybe you just

like organizing your stuff in a different way? In fact, most other

languages do not mandate where to keep your code: you can compile from

anywhere on your hard drive. The go tool expects to find

everything in the $GOROOT.

Otherwise you will need to muck with $GOPATH, which is

suboptimal. I find it more convenient to manipulate code starting in the

current directory, not assume everything will be in a single place. But

apparently I’m in the minority here?

Tooling

Since we are already speaking about tooling, let’s complain about it at length.

gofmt

It should be great when the creators of a language also give you a nice formatting tool. But

remember, kids: gofmt is brought to you by the same people

who mandate

inlined brace style. So they saw it fit to remove spaces as an

option and now mandate tabs for indentation, and spaces for automatic

alignment.

Oh and about automatic alignment: suppose you have this variable declaration at the top:

var (

i int

)Then you decide to add a new variable value and run

gofmt afterwards.

var (

i int

value int

)Voilà! The first line has been reformatted adding several spaces.

Looks nice with both variables lined up at the int, right?

Now your diff tool says that two lines have changed. Each long variable

you add will increase the number of lines changed making it impossible

to trace a particular change.

Other tools for other languages do the same mess, but at least they

are not official. You can always not use gofmt at your

peril, of course. But remember that the rest of the world will probably

do.

Momentum

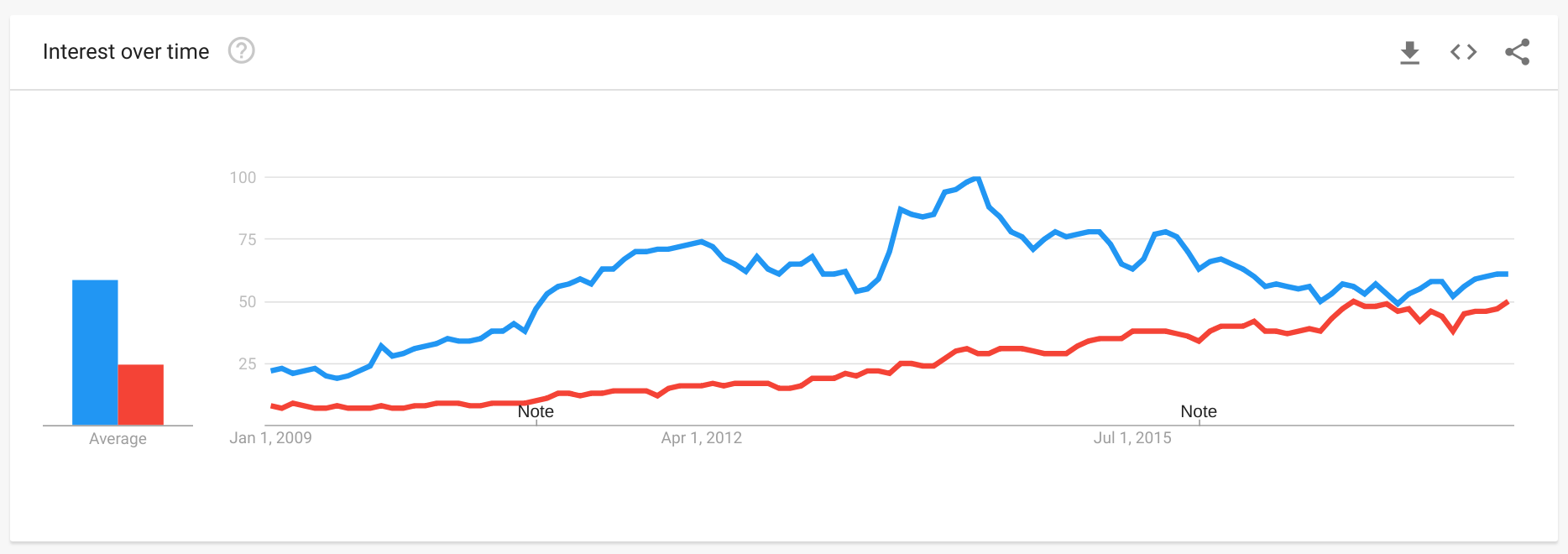

The ability to maintain a project long-term depends on how attractive it is to its potential developers: it is hard to look for candidates to work on an unpopular language or framework. And the hype around Go seems to have largely subdued. Data from Google Trends shows that Go has peaked:

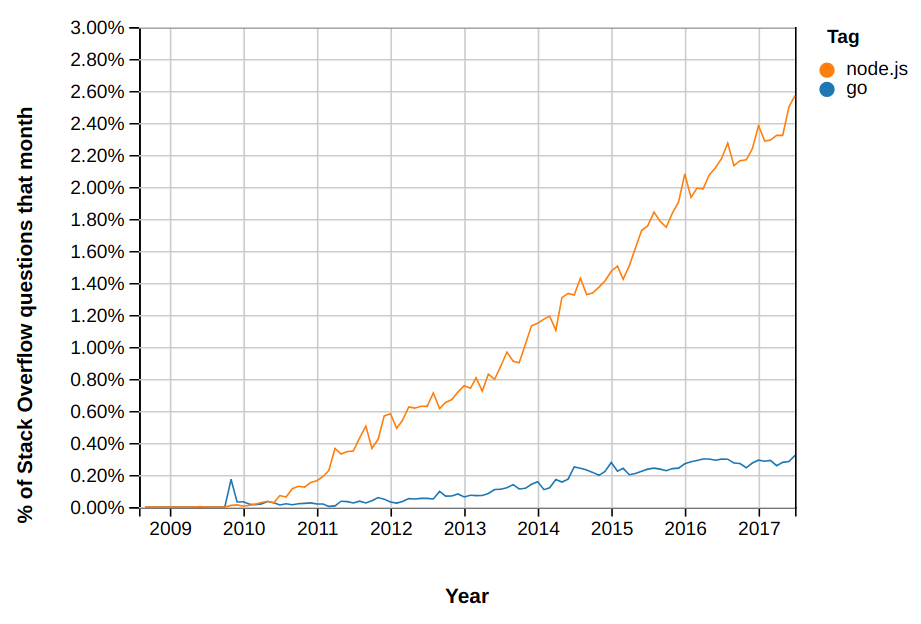

This dataset is however largely suspect: Go is always above Node.js and starts at around 25% before it was even announced. I fear that not even Google is able to filter correctly such a common word. Let us see data from Stack Overflow Trends:

This looks more like it.

Go is in a weird situation with regards to community: it is controlled directly by Google limiting the ability of others to influence its design. This poor starting point leads to a paucity of collaborations in libraries, and to a weak community around it. But Go people are apparently happy so they are not likely to do anything about it.

The opportunity for Go to be the new C seems to have come and passed. A large part of Go’s early appeal was based on being as fast as the proverbial speed king. In practice it is about as fast as Java. Add to this that using Go channels can slow your program down a bit, and they are the main concurrency primitive in Go.

The momentum has gone largely to Rust, which performs about the same as C and much faster than Go. Rust is at the same time very well liked by the community. In short, Rust appears to have stolen Go’s performance thunder.

At the same time Node.js has not lost an iota of popularity, even with the high profile defections. Its robust appeal comes from using JavaScript which is still evolving rapidly. Even if it is not as fast as Go it happens to be fast enough for most applications.

Conclusion

A successful organization needs to carefully evaluate a language or platform before using it for any significant projects. A largish project comes with a long-term commitment to maintain it. Adopting a new language also brings the implicit compromise to hire knowledgeable people. Go does not look like a solid bet for large projects at this point.

Apart from the corporate babble there is a glaring conclusion: Go quickly stops being fun when more ambitious projects are tackled. The language is cumbersome and has suffered from a lot of weird choices; it does not seem like they are going to be revised any time soon. The toolset is not as good as it believes it is. I think that Go can still be a good fit for small utilities that require better computing performance than Node.js but do not need the power of C, although Node.js is closing the performance gap rapidly.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Hynek Schlawack for the kind comments. Thanks to SamuelAFalvoII for the on point criticisms. Thanks also to everyone else that has helped me on Twitter with #golang for their immense patience.

Published on 2018-05-28, last modified on 2018-06-03. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.