API First

Written by David Bonilla, translated by Alex Fernández

It’s still hard to get into our heads that Internet use is mostly mobile, and that our web applications should therefore be mobile first.

Lovers of king-sized monitors may argue that most of that mobile traffic is personal or recreational, so that this mobile first should be centered on consumer (or B2C) websites. What nobody debates is that, whatever our software does, we will have a competitive advantage if we design our applications to be API first.

Any professional that has been in our line of business for longer than five minutes knows what an API is, although not many would be able to explain it to a ‘muggle’ without programming superpowers. An API is a formal specification that defines how to interact with a software application, and abstracts away the details of how it is implemented.

I suppose that the best way for the keenest reader of the Bonilista (David’s mother) to understand the concept is by way of demonstration. Matt Chilling has published an API to obtain Chuck Norris jokes. Combining it with Telegram’s API, for instance, I could develop a little program in less than an hour to publish a Chuck Norris joke every day at 7 AM on my school mates group… and also six job offers. All this without having the slightest idea about what database Matt used, or in which programming language was Telegram built.

Now that even David’s mother knows what an API is, we need to explain the benefits and advantages when our applications offer one.

The main reason for not wanting to implement an API is to believe that nobody will use it: who would want to connect to our software, and why? But we can also counter-argue that people need to know that they can connect with our software before they consider actually doing it.

During a dinner a few weeks ago, my friend Claudia suggested the possibility to republish all Manfred job offers related to project management and agile methodologies over at her portal CertificaciónPM.com, something that would report benefits to us both: she would offer relevant jobs to her pupils, and my offers would reach a broader audience.

I asked Claudia if she had an open API, because we had not yet partitioned and opened ours, but sadly she did not; so this particular integration will need to wait. How many similar opportunities are we missing?

After all, a public API can have an immense influence in the strategy of a company and even its work philosophy, making them more open to integrate and cooperate with third parties. Something that seems essential for companies that base their business models on the creation and management of a Community, such as any marketplace.

And even if you don’t want to open your software to the world, implementing an API is still a good idea. We work with personal data from our users that requires special protections, and it makes sense that nobody should be able to directly access the data, not even us; only through a private API, carefully secured and with restricted access, recording who, when and how has read or modified anything.

For the rest, you can create a second API — a lot more open but still with restricted access, for instance to read job offers — that limits the damage caused by a potential security breach. Today we may be the only consumers from our own website, but tomorrow we might be using it for a mobile application, a new product, or finally allow a third party such as CertificaciónPM to use it without having to modify our code.

All this is evidently not free. An API is essentially a contract where we commit to maintaining certain software services that will be consumed by third parties to construct their own. If these services are interrupted, or modified without warning, this will affect the whole ecosystem that has grown around them; the same risk you run with the APIs you consume. That is why Naval Ravikant, well-known entrepreneur and technology investor, has said:

Beggars build on APIs, sovereigns build on open source.

What Naval says may well be true, but it’s also true that the age of absolute monarchies is luckily behind us. 30 years ago there were very few software companies, and it was usual for them to develop internally every line of code for their products. Our industry has matured during this time and it has generated — like any other mature industry — its own supply chain in the form of API providers that have lowered the barrier of entry, allowing us to develop our applications without having to start from zero or reinvent the wheel.

This supply chain can evidently fail: any provider can go broke or leave us up and dry, just as in any other industry. This possibility should not paralize us: Citroën doesn’t start manufacturing safety belts or electronics for their cars because it fears that any of their providers can fail or disappear; instead they keep alternatives ready should anything unexpected happen. For those who are not lucky enough to count with infinite means, it’s well worth the risk.

At this point I have to confess that, for me, implementation of an API is not just a technical or business factor, but also ideological. Opening our application (however modest it may be) for others to use it, we contribute to democratize software development, and also to the ideal of an egalitarian, interconnected and collaborative Network that was once featured prominently in the dreams of the creators of the Internet.

We should be able not only to interact with other people, but to create with other people.

— Tim Berners-Lee (1999)

Are You Interested In This Issue?

David shares links with all data and information referenced in the article, compiled in a Gist (in Spanish).

Acknowledgements

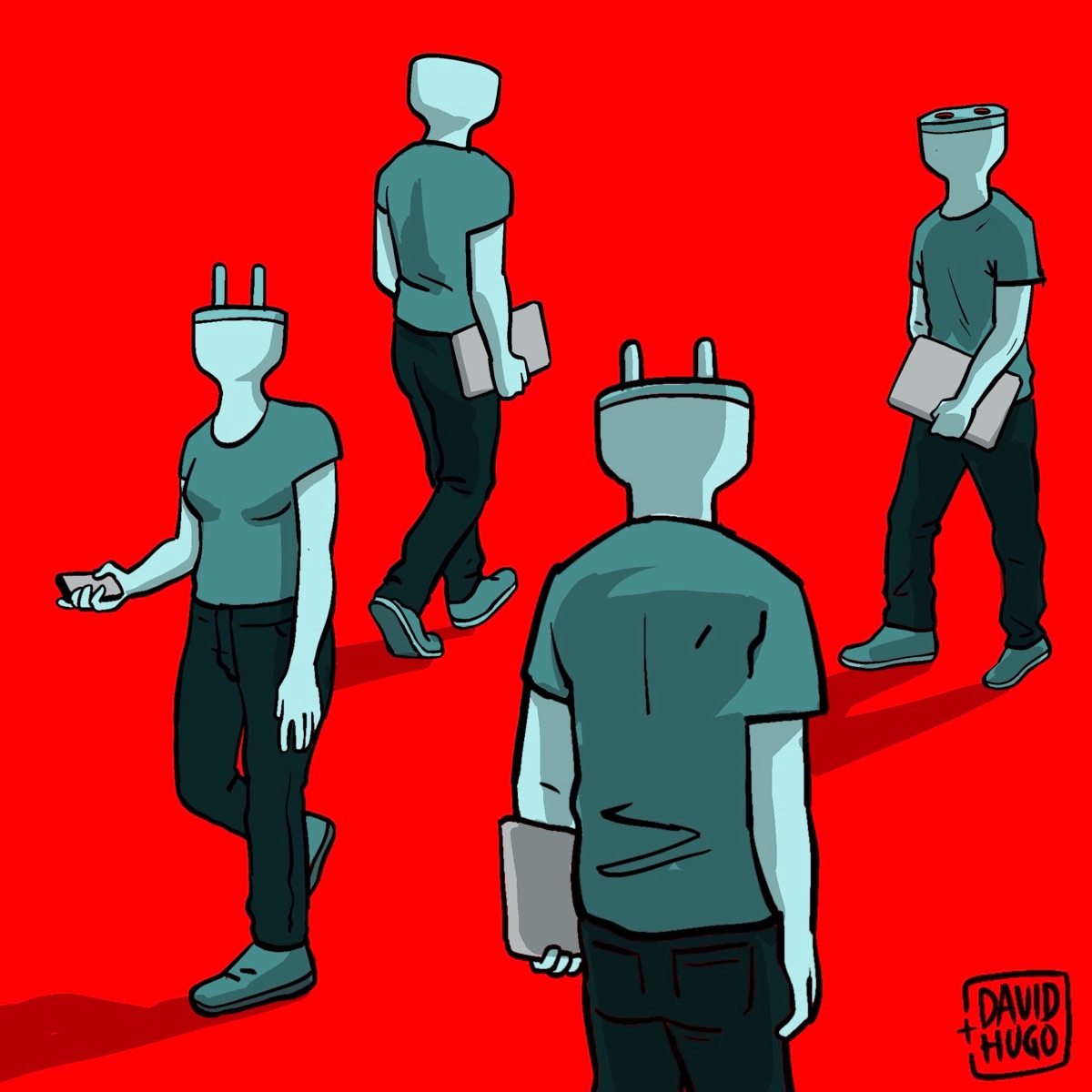

Thanks to David Bonilla for his kind permission to translate and publish his original Spanish newsletter, and Hugo Tobio for his kind permission to reuse his original image.

Published on 2021-08-16, modified on 2021-08-18. Translated by Alex Fernández from the original Spanish neswletter Bonilista 2021-07-18, by David Bonilla. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.