We Are Not Living in a Computer Simulation

On the Road to Quantum Entropy, Part 2

This is the second part of our journey to understand quantum entropy. In the first part we saw that the physical concept of entropy is basically another name for “information required to describe a system”, and that both always grow as time passes. This basic result will be essential in what follows.

Living Inside a Computer

A few years ago certain celebrities started divulging the idea (not at all new) that we are living inside a simulation. Among them: Elon Musk, Neil Degrasse Tyson.

The philosopher Nick Bostrom advanced this wonderful argument: there can only be one real universe, but inside it there can be any number of life-like simulations. Therefore it is much more likely that we are in one of those simulations than inside the real universe, just because of probabilities. After all, if there are many tickets but only one gets the price, all things being equal it is much more likely that we don’t win the price. Isn’t it just common sense? Well of course, provided all things are equal.

For the purpose of this article, the Simulation Hypothesis is the idea that we are living inside a computer simulation, and the Simulators are the hypothetical creatures that are running the simulation where we supposedly reside.

A Thermodynamical Argument

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that:

The entropy of an isolated system cannot decrease; it will either stay constant or increase.

As we saw in the first part, entropy is just another name for information to describe a system. If information is always increasing in our universe, there is no way that a computer can simulate it. No matter how big it is made, at some point any computer will run out of information storage.

This is the basic idea that proves we are not living in a computer simulation.

Thermo Tricks

There are many tricks in our simple formulation of the Second Law. First, it may apply to an isolated system, but what happens to an open system? Its entropy can decrease as long as it is transferred to another open system. All in all, entropy for the combination of both systems cannot decrease. The same idea applies recursively to any combination of systems until we reach the whole universe.

Next, we may ask ourselves: what if the entropy of the closed system stays constant, neither decreasing nor increasing? This doesn’t help either: the entropy of a closed system will only remain constant for a reversible process. Any transfer of energy done in finite time is irreversible; only theoretical, infinitely slow processes can be reversible.

Robustness

Is there any way to scape that Second Law? Sir Arthur Eddington stated:

The law that entropy always increases holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations – then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation – well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.

It has also been shown to hold at cosmic scales, that is, to the whole universe.

What Is a Computer?

So our next line of attack will probably be to redefine what a “computer” is, so that it can accommodate an always-increasing simulation.

Turing Machines

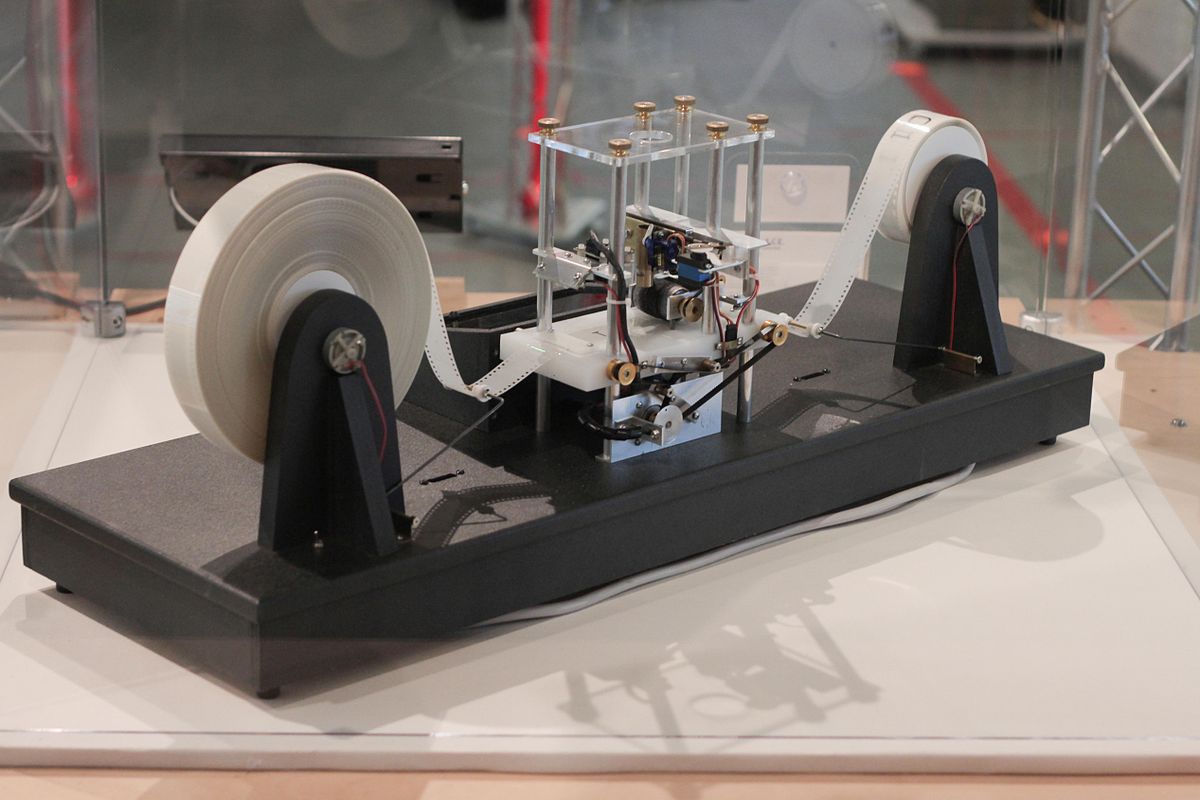

When Alan Turing started studying how computers worked in practice, he came up with an idealized version: a reading / writing head that could move in either direction over an infinite roll of tape with 0s and 1s. Such a machine could store infinite information so our little Second Law limitation would not be an issue.

The Turing Machine is a brilliant construct for exploring the theoretical limitations of computers: anything that it cannot do will never be possible on a real computer, no matter how many exabytes of memory we attach to it. But the opposite is not true: Turing Machines can perform infinite computations and run for as long as we desire, something that real computers cannot do.

A real computer is by necessity a machine with fixed bounds. Even the mythical cloud is large but not infinite: the total computing power of the world can be clocked at around 4E+15 MIPS. All the datacenters in the world will be exhausted at some point. Even a fictional Matrioshka brain, powered by the entire energy output of our Sun, will be exhausted at some point.

We can imagine that the Simulators attach new memory banks to their simulating contraption as needed, perhaps even as their sole dedication. Doesn’t matter: at some point they will run out of memory.

More Powerful Universes

One interesting trick is to postulate that the Simulators live in a higher dimensional space than us, the Simulated. Our whole universe would just be a lower dimensional slice of their awesome universe, as an infinite plane would be to us. This possibility sounds cool and is hard to disprove. On the other hand, information will run out in any higher dimension anyway.

As the next step, we may postulate that the universe of the Simulators is much more powerful than our own. As a starter, maybe it has a higher speed of light, or smaller Planck constant. Perhaps the fine structure constant there is not 1/137, but more like 1/1370, or 1/13. It remains to be seen if such a universe is even possible, as the constants of our own universe seem perfectly adjusted to make our existence possible.

And maybe the Second Law does not apply there? In this case information does not accumulate by necessity either: therefore data can be lost spontaneously, which would not help as much as we may think in the beginning.

Universe Simulates Universe

Information will also accumulate in the universe of the Simulators. So what if they take advantage of this fact? Maybe the whole universe of the Simulators is dedicated to simulating our own.

Notice that we are getting way more exotic than in the begging. We are moving further and further from the naïve argument of the probability of living in a simulation, which is that there are more simulated universes than real. Exotic universes are perhaps possible, who knows? Now we have to imagine universes dedicated to simulating other universes.

At this point we may as well wield any of a number of philosophical instruments. We can start with Hitchens’s razor:

What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.

Alder’s razor, also known as Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword:

We should not dispute propositions unless they can be shown by precise logic and/or mathematics to have observable consequences.

The Sagan standard:

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Popper’s falsifiability principle:

For a theory to be considered scientific, it must be falsifiable.

Nobody can prove that there is not between the Earth and Mars a china teapot revolving in an elliptical orbit, but nobody thinks this sufficiently likely to be taken into account in practice.

And of course their most venerable ancestor of them all, Occam’s razor:

Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity.

To be honest we might have started with any of these razors and be done with, but at this point they apply beautifully: we have shown that simulating a complete universe requires at least infinite computers, and then probably exotic universes. We may as well postulate that our universe is the dream of a butterfly, and we will have exactly the same proof (or indeed logic behind it).

What Is in a Simulation?

Our celebrity interlocutor who is a fan of the Simulation Hypothesis, being clever and charismatic, will now turn their celebrated eyes to the other side of the equation: to bend the concept of simulation so that it fits what their imaginary, almost unimaginable, and yet finite computer can do.

Limited Simulation

The first obvious tweaking of the Simulation Hypothesis is that the Simulators may not want to simulate our universe till it reaches the heat death. Since their computer will reach their computing limitations at some point, they just want to get to the interesting parts, which for us humans is exactly our own period.

This leaves us in an uncomfortable position: maybe the Simulators think that the really good part was the emergence of large-scale structure and they are about to switch our universe off at any moment. It could well be that they are running a few extra eons just to prove some fine point in their cosmological simulations, like (let’s use our imagination here):

If we change the fine structure constant from the actual value (for them) 1/138 to 1/137 (our own), do stellar clusters still arise?

They may not even be that interested in intelligent life forms such as our own, because they have probably seen it all by now. Almost by definition their intelligence is much higher than our own, so we will look like funny toys or artifacts to their eyes.

But wait! Perhaps the simulators are watching closely how civilizations evolve around the universe, to settle some refined bet in a gentleman’s club not unlike that one where Phileas Fogg sat with his pals, only with mixed-gender attendance and much more advanced in all other respects. They rented some hyper-computing instances on a galactic cloud and are waiting to see advanced civilizations. Problem is, the universe is almost 14 billion years old at this point, and we are still at the beginning!

Who can tell what wonders may arise in some particularly stable white dwarf with a planet right in the habitable zone, which will be there for more than a trillion years? What if their computing power runs off at this most exciting point? Will our intrepid betters see all of their efforts blow up in a puff of air as their galactic credits run out to run the simulation any further?

It is a sad fact of Nature that the Simulators cannot just continue simulating those parts they find interesting, while lowering the resolution (or even neglecting) other less interesting parts. Our universe is interconnected: we can gaze into the skies to see galaxy clusters millions of light-years from our own, we are pierced every second by neutrinos that come from the wildest corners of the sky, and instruments like LIGO can detect neutron star mergers where we barely see anything at all.

Again, since we are just entertaining wild speculations, we can imagine the situation we prefer. But simulations are not cheap: in the current state of our technology we can hardly simulate even one molecule of protein with sufficient precision as to know its final shape. Venturing that some advanced civilization can simulate a complete universe from start to any random point in the future more advanced than our own age is again going too far with zero evidence.

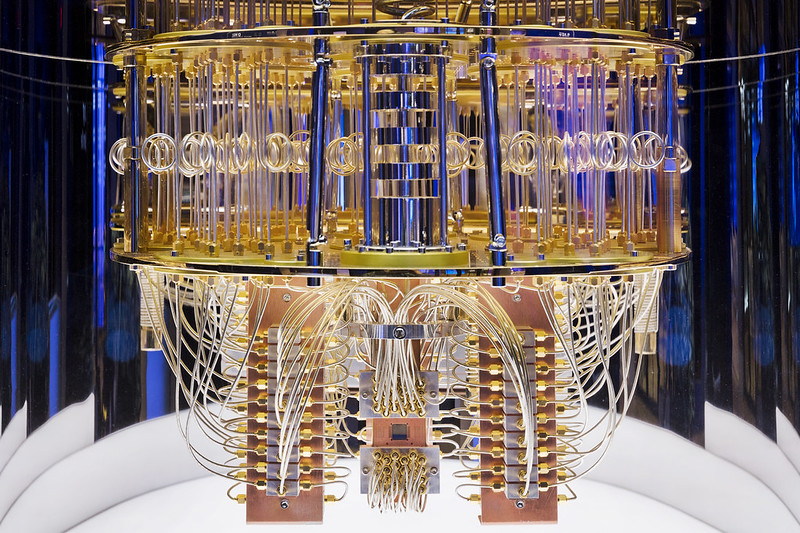

Quantum Computing

By now at least half of my remaining readership is probably screaming at the top of their lungs:

But it’s a quantum computer, you silly person!

When there is a far-fetched hypothesis, mixing it with a far-fetched technology is usually good to win the discussion. After all, qubits (short for quantum bits) are supposed to store much more information than regular bits, right?

We are getting a bit ahead of ourselves in this series, since I would like to do an entry about quantum computing. But besides the well-known difficulties with having many qubits running at the same time, the biggest issue is that the universe is also quantum. We get no huge boost from using qubits to solve classical problems. The number of qubits required to simulate our universe would be the number of qubits in it, and this number is still growing all the time (remember our Second Law).

There is an intriguing (and very remote) possibility: that decoherence forces our universe to be mostly classical, and that quantum computing can be applied to accelerate computations of these classical interactions. The harsh reality is probably that the same conditions that force decoherence in the real world will decohere our qubits, so it’s a zero sum game.

We are back to making far-fetched suppositions: that a new computing paradigm will store many qubits in one qubit, or that the simulators can compress qubits by a factor of a googolplex. It is still nonsense and should be discarded by our philosophical Swiss Army knife.

Enter The Matrix

If it’s impossible to simulate a complete working universe, is it possible that we live in a Matrix-like simulation? In the 1999 film The Matrix there is a simulation created just for us, limited human creatures, to live our little lives in a certain portion of time.

The plot of The Matrix falls short of the Simulation Hypothesis: we are not simulating a complete universe with people in it, but instead we need a bunch of living human bodies to plug them in the Matrix. Then there’s the whole plot gap that it is impossible to use humans as batteries: we will always consume more energy than we generate, also a consequence of the Second Law by the way. But what about the simulation aspects of the movie?

A certain version of the computer simulation could be possible: if it is restarted whenever the person in it dies. There is nothing unlimited in the life of a person, so in theory it could be successfully simulated in a limited computer. But note that this is a much more solipsistic version of the idea. It is not a simulation of our whole universe; just of the life and experiences of a person. In fact every person would have to live in a separate universe.

The thing starts to complicate if everyone in the Matrix shares the same simulation, as depicted in the movie. In this case information starts to accumulate again: even if one person dies and their information is removed, some of that information needs to be kept around because other people will remember it. Even in this limited scenario information grows uncontrollably: we will have artifacts from long dead people, word of mouth and after a while even recordings that need to be kept around. After a few generations the system would be expected to collapse. We can postulate “glitches in the Matrix” that happen whenever the system needs to erase information to make room for new experiences, but they would be noticeable to the inhabitants, like the infamous deja vus that the characters experience at some point.

Even if we limit ourselves to one generation, keeping information about the external world coherent would require us to simulate the whole universe. After all, anyone in the Matrix can take a picture of the galaxies in a certain portion of the sky, store it somewhere, then take another a few years later with another telescope and check if they are the same. It would take a very clever computer to maintain all the relevant information of the universe so that both pictures are coherent with all physical laws: they should be mostly the same, except for the moving of the stars inside and the occasional supernovae.

It is impossible to do a perfectly coherent simulation: any simulated laws of Physics are always short of the real deal. One example is anisotropy: if we measure the laws of movement in all directions we should be able to tell how the building blocks are aligned, that is, where the axes of coordinates are. Some researchers have even proposed looking for the telling signs of such a simulation in our world.

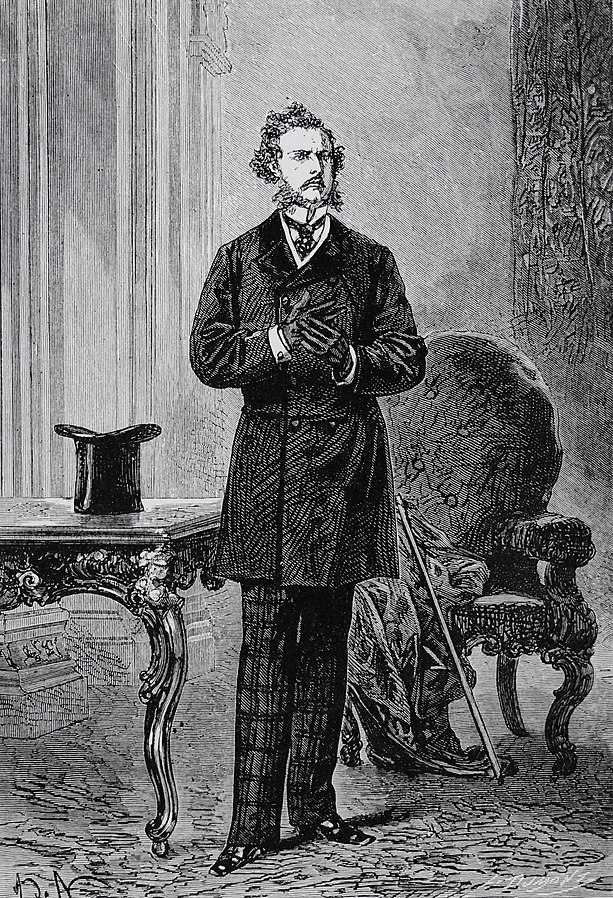

Bostrom’s Simulation, Finally

Remember Nick Bostrom, who postulated the Simulation Hypothesis in its latest incarnation? After much meandering we arrive to the core of his argument. It may be worth your time reading Bostrom’s original piece, if only because it is thought-provoking. Right in the abstract he states his “trilemma” (dilemma with three possibilities), where one of the following options must be true:

- the human species is very likely to go extinct before reaching a “posthuman” stage;

- any posthuman civilization is extremely unlikely to run a significant number of simulations of their evolutionary history (or variations thereof);

- we are almost certainly living in a computer simulation.

He calls this kind of simulation of our ancestors for prolonged periods of time an “ancestor simulation”. Then he shows a bunch of huge figures showing that running this ancestor simulation will be possible in less than a second, on some kind of futuristic planetary computer not unlike the Matrioshka brain mentioned above.

His conclusion is, as paraphrased from his website:

Either there is a significant chance that we will one day become posthumans who run ancestor-simulations, or we are currently living in a simulation.

And herein likes the problem. Bostrom seems to think that posthumans will necessarily run these ancestor simulations (option 2 above), unless they don’t want to for some unfathomable reason. Well, as physicist Sean Carroll says, maybe it’s not that easy to run an ancestor simulation.

Bostrom speaks about simulating our ancestors’ brains and their input, but in a quite fragile way. Apparently it should be easy to simulate a human brain with a digital computer, just by digitizing brain cells. Imagine running a Matrix-like simulation, but also having to simulate the brains for many generations of a species. This is not like running Conway’s game of life on a big board: I doubt it is even possible to replicate human brains with a crude simulation that just has zeros and ones, and still get conscious creatures. But suppose for a moment that it can be done.

How can the simulation be kept reasonably coherent? Anyone who has played games for a while quickly starts to get patterns, repetitions and inconsistencies. Under the Simulation Hypothesis, all simulated entities get unlimited freedom to do what they like. For instance, if in my world I get an EEG, would it reflect my real brain waves, or just be some standard (or randomized) graph? What about an MRI? What about a technology which hasn’t even been invented in the Simulators’ universe, like perhaps deep brain stimulation? Should this technique do anything to the simulated brains? Does the simulation need to be prepared for anything?

Bostrom centers on the amount of computing power, but he disregards information storage which is the real issue. Keeping a coherent view of the universe for one person is hard enough, but storing the world for a civilization of advanced beings that perform all kinds of low-level experiments and can look into quantum states of the matter at will is impossible without a very detailed state of the universe. As always, the amount of information required will grow without bounds.

In the article we find the following feeble defense:

Therefore, when it saw that a human was about to make an observation of the microscopic world, it could fill in sufficient detail in the simulation in the appropriate domain on an as-needed basis. Should any error occur, the director could easily edit the states of any brains that have become aware of an anomaly before it spoils the simulation. Alternatively, the director could skip back a few seconds and rerun the simulation in a way that avoids the problem.

Both scenarios sound anything but easy to me: editing brain states to avoid inconsistencies is probably NP complete, and rewinding the world will very likely run into many other inconsistencies, until the whole thing is just endlessly rewinding. As a trivial counterexample, my brain has become aware of many anomalies in the world before, like deja vus, and it was neither edited nor rewinded. Does this prove that I’m not living in a simulation?

Again we are back to simulating the whole universe as the only sensible scenario, which even Bostrom acknowledges is an impossible task.

Why a Simulation?

If it’s so clear that we cannot live in a computer simulation that any Internet rando with a blog and an elementary grasp of Physics can disprove it, why do so many clever people insist that we must certainly be living in a simulation?

I think it is psychologically comforting for people to downplay their existence: inside a computer simulation it is not so important that our world is cruel, or unfair, or just plain weird; those are just settings that the Simulators are playing with. It is not so different from the mechanism that makes some religions comforting: this world is but a test of our spirits, the real life will come later in Heaven.

A Mythological Explanation

There is another possible explanation. According to the developer Marius Gundersen, referring to Wolfram Physics:

It follows the millennium old pattern of us explaining our existence using our most advanced technology. Ancient people (many places) believed we were created from clay, their most advanced technology and we believe we live in a computer simulation, our most advanced technology. Everytime between people have attempted to explain the world using their most advanced models or metaphors. And so will we in the future.

We have been inventing myths since we had the words to do it, and we will probably continue doing so in increasingly sophisticated ways. So be it.

Conclusion

The simplistic idea that we live in a computer simulation is plainly wrong. There is no sane definition of “computer” and “simulation” where our universe, or even our species, can reside. The Second Law of Thermodynamics with its ever-increasing information has most of the blame.

Moral of the Story

I believe it is important to confront the universe with all its marvel and misery. It is the only way to not evade our moral responsibilities, since there is nothing else: no other world where all wrongs will be righted, no further simulations to correct the incorrections in our universe. We need to do here and now the best we can to improve our existence and that of our fellow people.

We will soon continue our journey exploring quantum entropy. Stay tuned!

Acknowledgements

Your name could be here! Just send a comment or suggestion to the address given below.

Published on 2021-08-12, modified on 2021-08-12. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.