💫 Understanding the Limits of Physical Laws

On the Road to Quantum Entropy, Part 5

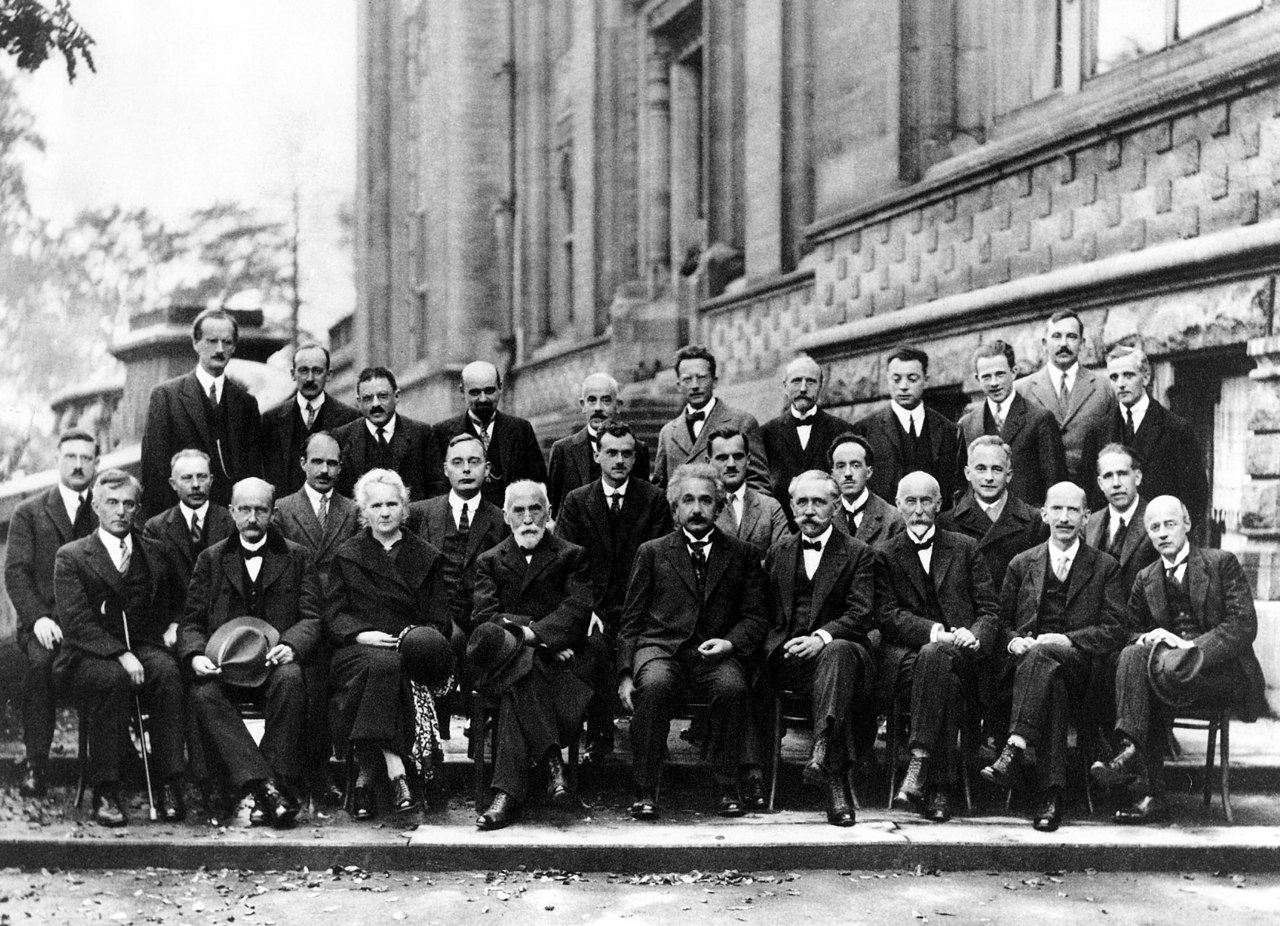

The most important works of Albert Einstein happened when classical laws were showing their limits, and gave birth to 20th century theories: special relativity, general relativity, quantum mechanics.

After more than a century of development, have we also reached the limits for these new theories? A short dive into the applicability of modern physics will bring us clues that may help us understand black holes, dark matter and some other theories about poorly illuminated things.

🔨 How to Break a Classical Law

We will start with an easy example.

🌡️ Newton’s Less Famous Law

Newton studied many things during his lifetime. Newton’s law of cooling appropriately studies how stuff cools down, and in modern terms it states that:

the rate at which a body cools in an environment is directly proportional to the difference of temperatures between the body and the environment.

So if the outside temperature is 20 C, a body at 220 C will cool twice as fast as another at 120 C. It’s simple, it’s elegant, and it’s not terribly accurate: the Wikipedia article explains a few corrections when the temperature difference is large, or when there is a lot of radiative heat.

This law is also not terribly interesting, in that it does not follow from any intrinsic principles of the universe. But it shows quite dramatically how it can be useful: inside its range of application, the temperature of a cooling object will converge to that of its environment following an exponential decrease. Outside this range the law is useless.

The most important lesson that we can extract from this example is of humility: laws should always come with application ranges, as an instruction manual.

🌌 Newton’s Eternal World

Let’s move on to more substantial matters (pun intended?). Kids at secondary school learn about Newton’s laws of motion, three very simple principles:

- objects in motion remain in motion when no forces are applied,

- when a force is applied on an object it will feel an acceleration inversely proportional to its mass,

- for every force applied there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Together with his law of universal gravitation, they explain a lot of things. After Newton published his Principia mathematica in 1687, so many aspects of the world were suddenly understandable: from apples falling from a tree to the orbit of the Moon around the Earth, including interesting things like bullets penetrating into sandbags.

Newton’s vision of the world was consistent with his religious views: the universe would be, like God, immutable and eternal. Gravity would hold things together in an infinite space.

After Newton there were many interesting developments in Physics: the reformulation as Lagrangians, Hamiltonians and later physical fields; a proper theory of optics, and finally the discovery of the laws of electromagnetism. But, important as they were, these advances were fully compatible with Newton’s world view.

It was not until the end of the 19th century, 200 years later, that his amazing building started to show cracks in the foundations. Up until this point everyone assumed that Newton’s laws applied to everything, from the smallest particles to the largest structures in the galaxy. Everyone was wrong.

⚛️ The New Quantum World

We have already seen how the works of Albert Einstein, were instrumental in creating new laws where the classical world broke down, along with many other brave pioneers.

In the smallest scales Einstein assumed that light was made of little particles called photons, which carried an amount of energy proportional to their wavelength; something that could not be derived from classical electromagnetism. Later advances in quantum mechanics would give a very different picture from Newton’s, with particles behaving like waves and crossing impossible potential wells in mysterious ways.

The limit for classical behaviour is not entirely clear, but at some point bigger than an atom yet smaller than a living cell we need to use quantum mechanics, or equations don’t work. We now know that many of the behaviours of proteins are quantum in nature, and the same applies to electronics circuits. Our modern world is literally shaped by our knowledge of quantum mechanics.

⚡ High Speeds

This was not all: Newton’s laws of motion didn’t hold water either for ever-increasing speeds. We have already seen how Einstein came up with relativity based on the fundamental idea that the speed of light was the maximum possible speed in the universe. This set a clear and well defined validity limit for classical physics: as an object gets close to this max speed its mass increases, making it harder to accelerate. It is easy to compute this correction for any speed.

Since the speed of light is approximately 300000 km/s, relativistic effects are negligible in everyday life. But they are relevant for GPS satellites since they move at 4 km/s, and would result in huge inaccuracies if they were not taken into account. Relativistic equations have been proven correct time and time again, and play a huge part in accelerators where particles can achieve 99.9999991% of the speed of light.

🌞 High Masses

The jewel of the old crown was not safe either: Newton’s law of gravitation would be the next to be demolished by Einstein. As successful as it had been to predict everything from the fall of an apple to the orbit of the Moon, it reached the limits of its application even within the solar system, since nobody had been able to explain the precession of Mercury.

Einstein created his general relativity considering that gravity was indistinguishable from any other acceleration. The consequences were really interesting: even light had to bend around massive objects. The philosophical effects were devastating. No longer there was an eternal and immutable universe. At some point Einstein wanted to reinstate this nice static picture using the cosmological constant, in what he called his biggest blunder. It was useless; the Big Bang would soon win hearts and minds, with its ever-changing universe.

🛑 Limits to the New Limits

Does it make sense to expect that the new laws would apply universally?

♾️ Shy Singularities

General relativity has been really successful. Even today, more than a century after its inception, general relativity continues to be validated against rival theories. GPS satellites have corrections for general relativity since they feel less gravity than we do on Earth. In the past few years we have seen black hole imaging using radiotelescopes, and then the detection of gravitational waves which had been predicted by Einstein himself (and then recanted, but that is a story for another time).

But general relativity is not perfect. Physicists like taking everything to the extreme, and it makes lots of sense because it’s the way to check the limits of a law. But sometimes they forget that every law has limits. When people started looking for interesting solutions to the equations of general relativity they found that there was a point at which light could not escape any longer. These weird solutions broke space-time: the equations yielded a “singularity”, a point where matter gathered with infinite slope. Any such predictions in any other theory would have probably been discarded; in general relativity they were just the start of a fruitful discussion.

In 1969 Roger Penrose postulated that the universe didn’t like showing a naked singularity, in what is now called cosmic censorship hypothesis; therefore black holes were hidden behind a Schwarzchild horizon into which we cannot ever look. In the 21st century we have been so lucky as to take a picture of a large black hole, or more precisely of its event horizon. It was exactly as predicted!

Does it make sense to expect that Einstein’s equations will be valid all the way, or should we look for another theory that will be valid at these extreme concentrations of matter? We do not know, and it is not terribly important since we are not going to be able to play with these tremendous forces any time soon. Furthermore, despite what films like Interestellar (2014) tell us, it is impossible to study a singularity from beyond the event horizon. Even gravitational waves as recently detected can only tell us how black holes behaved from the outside.

But we can at least show some humility, and admit that we don’t know a lot about what happens beyond giant stellar collapses. Perhaps general relativity is not valid at all inside the black hole horizon; it is very possible that in that last bit some other exotic theory of matter may take over and avoid the singularity. This possibility is however seldom mentioned at all, perhaps because black holes are just more flashy.

⚫ Dark Matters

There is another extreme at which general relativity is not a good fit for observations, and you have probably heard about it as the basis for “dark matter” or perhaps even “dark energy”. In fact, Newton’s gravitational law does not hold in these circumstances either. Gravity at large scales does not behave as we would expect it to: instead of being proportional to 1/r², it suddenly becomes proportional to 1/r. In large galaxy clusters gravity just reaches much further than it should. This effect is only noticeable at really large scales, at least the size of our galaxy.

It looks as if galaxies should contain more matter than what we see. In a display of imagination astronomers invented “dark matter” to make up for the lack of stuff: matter which cannot be seen but yet is there to pull things together. The problem was only magnified when we looked at gravity at even bigger scales, to the point where scientists had to postulate more dark than visible matter in any given galaxy.

The Wikipedia article is a wonderful mess of justifications for this “theory”, which in essence is just:

we cannot find what should be there so we postulate that there is this other stuff which serves the same purpose.

It is highly reminiscent of the epicycles invented by Ptolemaios to explain how planets orbited the Earth (and not the Sun).

After their success it is no wonder that other astronomers invented “dark energy” when there was another anomaly in the large structure of the universe.

I think it is much more reasonable to admit that general relativity may not apply at the limit of large scales. There have been many attempts at creating modified gravity laws that worked at large scales, known collectively as MOND. The dark matter proponents have subjected all these corrections to unreasonable requirements such as being able to explain observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation. Which they did anyway.

It would be good to have a way to select just one correct alternative for MOND, but it would not necessarily teach us anything new about our universe beyond a nice correct formula. But the most interesting aspect of a new theory is always that it can open the door to new discoveries; what strange force is there lying around that can generate corrections to gravity as we know it? After all, just piling up dark stuff has been particularly fruitless during the last few decades.

🔦 Speed of Light

What about the crown jewel of the new physics? Special relativity has been challenged many, many times, but every time it comes out victorious and reinforced: no matter what we try, the speed of light is still the maximum possible speed in the universe.

A little anecdote can illustrate the strength of this conviction. In 2012 a colleague at a previous job asked me what I thought about the discovery of a bunch of neutrinos that travelled faster than light at CERN. Apparently having 99 scientists signing the paper was a guarantee of good science, something which I highly doubted. And lo and behold, some months later the anomaly was correctly diagnosed as a faulty computer connection.

Am I so clever as to have guessed the correct option, or too arrogant to recognize that there might be a limit here that will prove wrong too? I was of course not alone in this intuition, nor especially prescient; special relativity is just the safest bet. In fact there is a joke among physicists about betting against the speed of light.

Special relativity works also well with all the latest theories, at least with those that work. So, as far as we know right now, special relativity is a fundamental truth. But only because it has been adapted to changing conditions. Of course this situation might change at any point; such are the mysterious ways of science.

🔬 Quantum Limits

On the quantum front there have been many improvements to the original crude measurements of the atom, like Feynman’s quantum electrodynamics: essentially a quantum reformulation of the classical laws of electromagnetism. Later came quantum chromodynamics to explain the terribly intense forces in the interior of the atomic nucleus.

The maximum speed of light applies perfectly well to quantum mechanics: in 1928 Paul Dirac came out with a relativistic version of Schrödinger’s wave equation. In fact this new Dirac’s equation is much more symmetric and nicer than Schrödinger’s, but we still use the old one at low speeds because it is simpler. As usual, it is just a matter of limits.

What about even smaller scales? The very suggestively named string theory was supposed to explain phenomena beyond the atomic nucleus, and in fact it should be the foundation for all quantum mechanics. But after many decades it has failed to yield any progress in our understanding of the quantum world. It is not clear that we even need anything beyond what quantum mechanics has to offer at the smallest scales.

At the same time it would be a bit arrogant to expect quantum mechanics to be just right at all scales. And in fact there is a natural limitation, as embodied by Planck units. I think that having clear limits is quite positive for our understanding, and it is a great stimulus for the search beyond quantum mechanics.

🔀 Decoherence

But to me it is much more interesting to explore the frontiers between the quantum and classical worlds. What happens when a quantum particle becomes classical?

This is exactly what Feynman and other great physicists were thinking about during the 50s. It lies at the heart of quantum decoherence, which hasn’t given all of its secrets away yet. But this is another long story which deserves its own article.

Conclusion

Physicists tend to stretch their laws beyond their initial range of application, and quite often interesting things happen in the process. Sometimes we just need to accept that we have no knowledge of what we are talking about. As an example, black holes are often referred to as singularities, which is just an extrapolation of our current knowledge with no basis in experiment. At other times we find really interesting stuff lying at the corners of our understanding.

We will soon continue our trip to understand quantum entropy.

Published on 2022-03-27, modified on 2022-03-27. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.