🤨 What Is Contradiction?

≢ Guide to Contradiction, Part 1

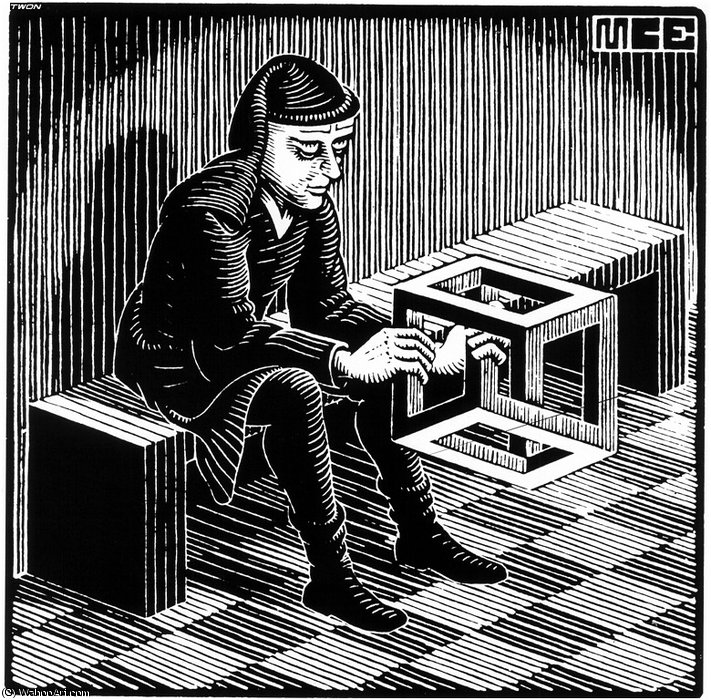

As reasonable people we dislike contradiction: it is one of the telltale marks of the cheating kid, of the dishonest politician, and of the feeble mind. However it is not easy to escape from its claws, and whatever we do to dispel it, it seems to come back to bite us in the ankles.

What should we do if we find a moral contradiction? Is it bad when our principles are contradictory? In this article we begin a study in this intriguing subject. I intend to understand how contradiction governs our life, and how we can deal with it when it happens.

Perhaps you think you already know what contradiction is; let’s start by deconstructing that belief.

≢ So, What Is a Contradiction?

In the field of logic there is a beautiful definition:

A contradiction means asserting that a statement and its contrary are true.

For instance, if I say that “it is one o’clock” and “it is not one o’clock” at the same time, I am immersed in a contradiction that needs to be solved one way or the other.

Simple, isn’t it? We are finished! Well, maybe not.

🕓 Time and Logic

Note that in this very simple example we are presupposing that there is one authentic immutable truth: trivially, both statements can be true at different times. If two people have different clocks, or live in different timezones, both may be right in their own way at the same time.

Statements also need to be precise: if someone says that it is not exactly one o’clock while another says that it is approximately one o’clock, both may be saying the truth.

But beyond these obvious conundrums there are deeper difficulties. Let’s start with Zeno of Elea; he famously came up with a series of paradoxes relating movement. The most famous one is the story of Achilles and the tortoise; here we will turn to the motion of an arrow. An arrow in its flight will be at one point at any given time. How can it move from one point to the next, if an any given time it is stationary in one point? We need to accept that somehow movement is made of discrete points, and at the same time it is a continuum of positions and instants.

Alright, so we have to accept the discrete and continuous nature of time and space.

🪪 Identity

On the opposite time scale there is the question of identity, illustrated by the ship of Theseus: an ancient vessel that was maintained and repaired for several centuries in Athens, which prompted the question: if all the original parts have been replaced not once but several times, is it still the same ship? Thomas Hobbes continued in 1656 by saying that by collecting all the discarded pieces and putting them together you could build a second ship of Theseus, which might arguably be more original than the original; which is absurd.

We are only getting started. Heraclitus of Ephesus famously said:

You cannot bathe twice in the same river.

But we will follow García Calvo with a more interesting version following the original sources:

In the same rivers we enter and do not enter.

Here we have the contradiction in all its glory. The river is the same and at the same time it is not the same; as the waters have been replaced by new ones coming down. We may want to call “the river” just the shores and the bottom, but we will soon realize that they are too being remodeled and replaced by the flow of water. Even the course of the river is slightly changing all the time, and will eventually be displaced and perhaps deeper. It is still by all accounts the same river.

🧠 Ideas and Properties

This time business is too complex; let us move to timeless statements then. The most common statements that are considered in logic are of objects having properties, like the old adage “Socrates is human”. So let us start with an unambiguous statement:

The sea is blue.

We are saying that the sea has the property of being blue. Such a plain idea should be valid everywhere and at any point in time, right? Except. As long as I can reasonably say the following sentence, we may have a contradiction:

The sea is not blue.

The sea has many hues of color depending on the time of the year. But we don’t have to deal with time again, so let’s agree that “generally the sea is blue”. So let’s ask our friend Homer of The Iliad fame what color is the sea: he will say at least 17 times in his works that it is wine-colored. Was he color-blind? Did he have an issue with colors? Yes, he did have the issue that the blue color had not been invented yet. Very likely he noticed that wine and the sea have different colors; but just as we call “blue” a wide gamut of colors, for the ancient Greek “wine-colored” also expanded a huge variety of tones, which happened to include the color of the sea at times.

The absence of the color blue in most languages until recent times leads some people to conclude that “early humans were colorblind” (source) including the ancient Greek. This absurd notion is a very common confusion of “perception” and “idea”.

💭 Reality

As we explored in The Amazing Mind, what we call “reality” is just the shared network of concepts and ideas that we handle. This reality is therefore separated from whatever we are talking about: there is some underlying world where we are speaking, which we can only perceive with our senses, and which can only be understood through our concepts.

So in reality we are dealing with human ideas. In truth there are no hours, no ships, no rivers, no time. All those are human ideas that we apply to understand the world around us.

At this point we may be tempted to say that this “underlying world” is just a bunch of atoms and other particles moving around, as a physicist would say; but we don’t want to fall into such a banal trap. Atoms and particles are just a different set of concepts and ideas that we apply to the underlying world, at a different level of “reality” to understand a separate set of aspects of the world. In fact in Physics there are many such levels, each one used to understand a set of phenomena; we might as well say that the world is only made of equations, of fields, of hamiltonians, of quanta, of Schrödinger’s equations or of superstrings; all would be valid at some level and all would be equally false.

Every time that we try to unveil the real nature of the underlying world, we are just imposing a new layer of ideas and concepts on it, that immediately come to be a part of our reality. We understand the world better, and at the same time we are farther away from it. As Einstein famously said:

As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.

The business of applying properties to objects will by necessity live in reality, and will be subject to our ideas of objects and of properties. It will have as little to do with the world as with our own perceptions; someone lacking the idea of “blue” will not be able to see something “blue” even when their senses are perceiving it directly.

🤔 Conclusion

We have seen that it is really not easy to find an example of idea which cannot be contradicted. But surely we will be able to find it when we study the realm of logic and mathematics!

So far we have only scratched the surface of what a contradiction can be. In coming articles we will deal in depth with logic, identity and the psychology of contradiction, among other things. This journey will be very useful to draw ethical conclusions which can hopefully make us live better lives. Such is our ambitious goal.

🙏 Acknowledgements

I can highly recommend the compilation and translation of the book by Heraclitus by Agustín García Calvo; unfortunately not translated to English as far as I know.

⏭️ To Be Continued

This is the first part of the series about contradiction.

- Part 1: 🤨 What Is Contradiction?,

- Part 2: 🧮 Contradiction in Logic and Mathematics.

Enjoy!

Published on 2023-06-03, last modified on 2023-08-10. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.