🪽 Aves Æternæ

🛩️ Building Perpetual Flying Machines

Last year I published an article about perpetual flying machines: flying machines that could stay aloft indefinitely. The initial numbers were intriguing: the concept was viable. But nobody has done it yet. Should we accept the challenge?

🏗️ Building Models

I set up to build more detailed plans with a given scale in mind. I expected to find a wall at any point where the required technology just wasn’t available, or it was too exotic to be purchased just yet. To my surprise there were no showstoppers: the technology is here, and everything seems to be feasible, right now. The engineering challenge is thus amazingly possible.

🎚️ Model Scale

So let’s build a scale model!

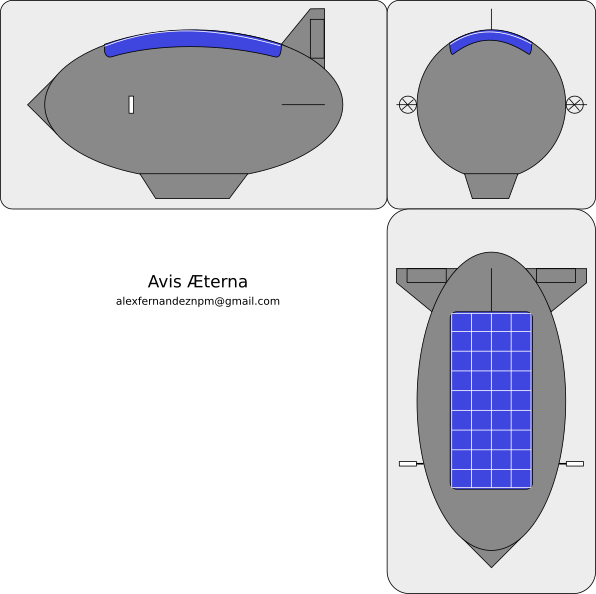

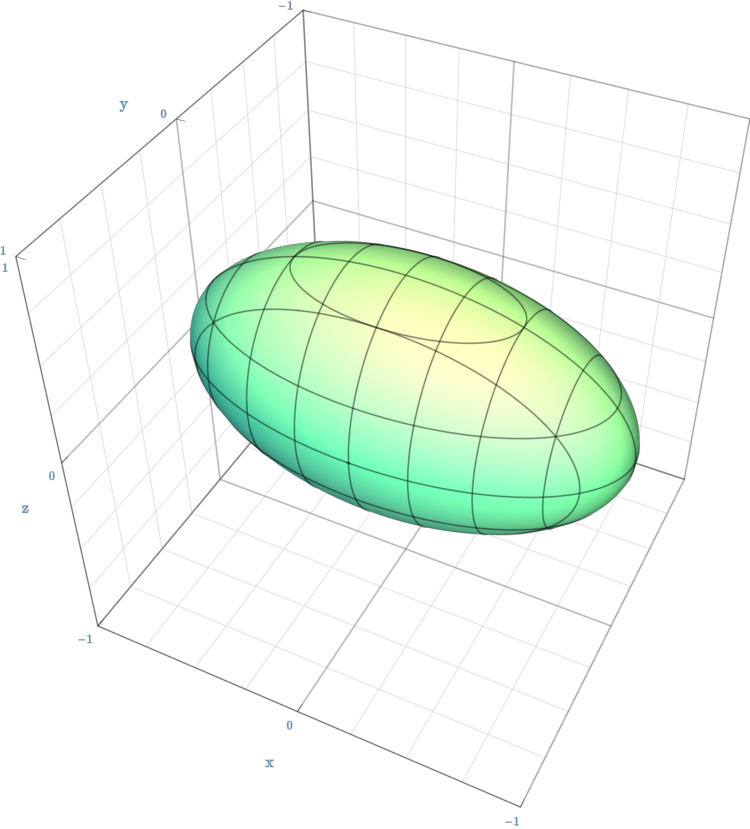

🏉 Shape

Let’s first look at the shape. The classical design for a blimp or a zeppelin is a spheroid. (Yes, I know that last time I chose a shape similar to a boat: square and with flat profile. I have since come to appreciate the classics.)

It is quite aerodynamic, or should be: the drag coefficient of a spheroid is between 0.02 and 0.04, according to GE Dorrington in “Drag of Spheroid-Cone Shaped Airship”. Also it is simple to model and build. So let’s go with a spheroid!

📏 Dimensions

An intriguing option is to size the avis aeterna vaguely like a car: two meters wide and tall, four meters long. (For US readers: that is 6.5 feet wide and tall, 13 feet long.) These dimensions are big enough to be substantial but small enough to be built in a garage with limited means.

This decision mandates all of the proportions of the model: with the

value of 2 m and the spheroid equations we

can compute everything else. First we have a prolate spheroid with axis

A=2m, and length C=4m. The volume contained

becomes:

V = πA²C/6 ≈ A²C/2,

which is a surprisingly accurate formula (actual factor above should be 0.523). In our case:

V ≈ 2m × 2m × 4m / 2 = (2m)³ = 8 m³.

And the area is very approximately:

S ≈ 5 × 2m × 2m = 5 × 4m² = 20 m².

These are the basic parameters of our model.

⚖️ Weight

You may remember that the plan was to fill the airship with hydrogen: even lighter than helium, and quite cheaper. For an uncrewed vehicle the risks are negligible. Also, for a continuously flying machine hydrogen can be replenished in flight, as we will see later.

How much will our model weight? Exactly as much as the air displaced by the hydrogen: we compute the weight of the air inside, and then subtract the weight of the same volume of hydrogen. Since the density of air is 1.3 kg/m³, and of hydrogen is 70 g/m³, lift will be:

`L = (1.3 - 0.070) kg/m³ × 8 m³ ≈ 9.84 kg.

So our weight budget is around 10 kg. As you see, at this stage it’s not enough to do Fermi estimations (i.e. order of magnitude): for a detailed feasibility study we need more precise numbers. It is still OK to round up numbers as we did above with surface and volume.

🛠️ Build

How can we build a real life airship, even if it’s a small one?

🪚 Structure

We want to build a dirigible: an airship which is sustented by the lift of a light gas. In fact we want a rigid hull instead of an inflatable structure. We know that dirigibles worked beautifully even with ancient 1900s materials; is it possible to build one at this scale?

Let’s go with the simplest structure: just a shell. We can set up a rigid hull that contains a sack, which in turn holds our lifting gas. What is the weight per square meter that we can afford?

First we have to set up a weight budget for this concept: how much of our 10 kg we want to spend in the shell. It seems unavoidable that this is going to be our biggest source of weight, and that we should reserve as much for it as we can afford: a stronger structure is going to hold up better against strong winds or impacts. Let us say half our weight is for the structure.

We have to reserve some weight for the wings and other parts, leaving perhaps 4 kg for the hull. Since we have 20 m² of surface, the areal density will be:

D(A) = 4 kg / 20 m²,

D(A) = 200 g/m².What kind of material can be strong enough at 0.2 kg per square meter? Carbon fiber should fit the bill. It is a very interesting material made of carbon fibers embedded in an epoxy resin, which when cured results in super strong panels.

🪽 Wings and Reinforcements

We have set aside a budget of one kg for the rest of the hull.

The wings need also be built using carbon fiber. They need to be even stronger than the outer shell. The two wings and the tail on top are of the same approximate dimensions: 60 x 80 cm, for a total area of approx. one third of a m². The three therefore share an area of 1 m². The areal density needs to be at least twice of the shell, probably 500 g/m², for a total weight of 0.5 kg.

Also some reinforcements are required where the parts are joined. It is impossible to build the hull in one go; different pieces have to built and assembled. In our case we can build eight identical panels, which is quite convenient from the manufacturing point of view. Those can then be assembled together using reinforcements, built using carbon fiber and some glass fiber for elasticity.

Finally we need a small cone to place at the front. Together the objective of 1 kg seems doable.

🎈 Hydrogen Sack

Inside the hull a large bag will hold the gas. At this scale we don’t want a complicated set of sacks containing the hydrogen; just one big bag will do.

Helium balloons are usually done with Mylar, but there are materials that leak even less hydrogen: PVA is a very strong contender. In “Internal polymeric coating materials…” Lei et al experiment with several coatings, finding that PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) has the lowest hydrogen permeability.

Luckily it is not hard to get PVA bags, as they are widely used in industry because they are biodegradable. One precaution is that PVA dissolves in water, so the interior of the structure must be kept strictly dry.

Bags with thickness of 40 microns are quite common in the industry. Given the density of PVA of 1.19 g/cm³, for our total surface of 20 m² we get:

W(bag) ≈ 0.040 mm × 1.19 g/cm³ × 20 m²

W(bag) ≈ 950 g ≈ 1 kgSo another kg for our weight budget, for a total of 6 so far.

💨 Hydrogen Leaks

How much hydrogen would leak out of our PVA bag in a day? This of course depends on how well sealed the bag is and the quality of the materials. We can use a unit of permeability called Barrer to quantify it. Again in Lei et al’s study the permeability of PVA is given as 0.0084 barrer. Given the definition of 1 barrer in SI units:

1 barrer = 3.35 × 10^-16 × mol × m / (m² × s × Pa),

the formula for leaked gas is a bit messy, so bear with me. Leaked quantity can be computed as follows:

Quantity = permeability × surface × time × pressure / thickness.

We computed a total surface of 20 m², which also holds

for the internal bag. We want to find out the leaked quantity for a day

so time will be 86400 seconds. The pressure

differential will be of atmospheric pressure or 101325 Pascal, assuming

that the external hydrogen pressure is nil and pressure inside the bag

will not be much higher than 1 atm; even small

balloons are only a few percent tighter than atmospheric

pressure.

Finally let’s recall that we are using a 40 micron bag. Now we have

everything we need to compute the daily leaked quantity

Q:

Q ≈ 0.0084 barrer × 20 m² × 86400 s × 101325 Pa / 0.000040 m,

Q ≈ 0.0084 × 3.35 × 10^-16 mol × 86400 × 101325 / 0.00004,

Q ≈ 0.0006 mol.Converting to grams is easy as 1 mol of Hydrogen is defined as 1 g, so we are leaking a bit more than half a milligram per day. Not bad considering that we have around 0.5 kg of hydrogen! We might stay aloft for a million days at this rate. These numbers do not look very realistic, and have to be contrasted with real world tests with real bags. In any case the safety margin should be enough to stay in the air for days or even weeks.

⚡ Energy Sources

The airship needs to be able to direct its flight. It needs a power source that gives enough energy for our purposes. Being a demonstration model it doesn’t need to withstand any kind of weather, but it needs to manouver at a certain speed.

🛩️ Power

How much power do we need? Let’s recall the drag equation:

F(D) = ½ ρ × v² × C(D) × S(front),

where the surface will now be the front area which is a circle of radius 1m,

S(front) = π × l²/4,

S(front) ≈ 3 m².Power is just force multiplied by velocity, so we just multiply this force again by the velocity:

P = F(D) × v,

P = ½ ρ × v³ × C(D) × S(front).So the power we need to move at a given velocity can be computed

using the front surface of 3 m², the density of air of 1.3 kg/m³, and

the average drag coefficient we saw above for a spheroid with a cone of

0.03. (Note: carbon fiber is a very polished surface so the

drag coefficient might be even lower.)

P ≈ ½ 1.3 kg/m³ × 0.03 × 3 m² × v³,

P ≈ 0.06 kg/m × v³.Now let’s set as target speed a leisurely pace of 10 m/s, or 36 km/h (22 mph). Our avis aeterna is not going to be a speed demon, but it will move about. The required power will be:

P ≈ 0.06 × 10³ kg×m²/s³ ≈ 60 W.Approximately 60 watt of power are needed to move at 10 m/s. Is this possible to achieve?

⚙️ Motor and Propeller

From this power target we have to discount the efficiency of motor and propeller. Luckily thanks to the RC industry there are a lot of very efficient motors (brushless and sensored are apparently the way to go) and propellers which are powerful and light enough.

There is at least a 20% reduction in efficiency due to the combination of motor and propeller to be taken into account. So our 60 W of impulse become at least 70 W at generation. Another important consideration is that the weight of two motors and two propellers should be well below 500 g.

For balance the propellers should be one at each side of the airship; this will also allow it to maneuver using differential power. They should also be near the forward of the ship to avoid instabilities.

☀️ Solar Energy

Where can we take our power from? If we want our avis to stay in the air indefinitely we cannot depend on carrying fuel aboard as it would be exhausted at some point. There are not many renewable sources of energy up in the air. The most obvious is the Sun: embed some solar panels on top of our hull and we are good to go!

Ultralight panels are not easy to find. But there are companies commercializing powerful panels today. One such example is the Solbian SP 24, which provides a nominal 82 W with a weight of 1.1 kg.

Keep in mind that solar panels tend to provide less power than advertised even in full sunlight. So it is possible that at midday in optimal weather in a temperate country this panel might get to give us the 70 W we need. We might use a couple of these panels to reach more power, but then the airship may become top-heavy and destabilize.

It is not unusual to see promises of much more powerful solar cells. MIT researchers were announcing 370 W/kg in 2022, which would be closer to what we need. And the Airbus Zephyr uses Microlink solar sheets exceeding 1500 W/kg and 350 W/m² apparently, or so they say.

We might even get to 20 m/s with this kind of power. But keep in mind that the cubed equation we got above for power is quite treacherous: to double our initial 10 m/s we would need 8 times more power, or 560 W. We will explore theoretical max velocity below. For now we will keep to our target speed.

🌬️ Wind Energy

An intriguing possibility which does not require any technological leaps of faith is to use wind energy.

But wait, how can you use wind energy to propel yourself if you are moving in the wind? It’s the same principle as regenerative braking in electric cars: you let the motor spin freely. Instead of spending energy to move the wheels, the movement of the wheels charges the battery. Same principle: Yokota and Fujimoto investigated the principle in planes in Pitch Angle Control by Regenerative Air Brake for Electric Aircraft, and it is perfectly possible if the wings are oriented correctly. It even decelerates the aircraft, which is to be expected since the energy is taken from the flowing air.

So the idea would be: orient the airship so the propellers move maximally, stop the motor and let it charge the batteries. The craft would slow down at the same time so it would not be carried away by the wind so fast. Then, once the batteries are charged we can start the propellers and move back to the desired position. This process can be repeated as often as desired; of course it will not be very efficient but might help not drift away too much whenever other power sources are not available, e.g. at night.

🔋 Batteries

Speaking of which, is there any of that weight budget left at this point for the batteries? They can be used to store some of the solar and wind energy during the day, and use it at night to avoid drifting away.

We will have to set aside at least 1 kg for a good battery. We can get 180 Wh commercially today. This means driving our propellers at 60 W for three hours, which is not bad, supposing we can charge it while there is sunlight.

💅 Finishing Touches

We still have to make sure this thing is light enough to get in the air, and then fly it.

💻 Control

Let’s start by how to fly it. An autonomous drone needs to have enough sensors to know where it is and what it is doing. Also an onboard computer and servos to move the control surfaces: ailerons on wings and tail.

Today it is not hard to get a powerful computer with GPS, accelerometers, camera, microphone, plus world-wide communications, into a compact package weighing less than 0.25 kg. We call it “mobile phone”. Also we may need something like a Raspberry Pi with electric controls to drive the servos. Ideally we should get something that does both functions, but we can equip both if necessary.

We can spare 0.5 kg for the onboard computer(s) while servos should take 0.2 kg at most.

🧮 Weight Budget

Let’s add up a few other weights: a strong gondola is required to hold battery and onboard computer below the hull, so it can help compensate the weight of the solar panels on top. It might weigh 0.5 kg. We also need some cables for which we will reserve 0.2 kg.

These are our total weights:

| part | material | weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| outer shell | carbon fiber | 4 |

| wings and tail | carbon fiber | 0.5 |

| reinforcements | carbon fiber | 0.5 |

| envelope | PVA | 1 |

| gondola | carbon fiber | 0.4 |

| battery | LiPo | 1 |

| motors | 0.1 | |

| propellers | 0.2 | |

| solar panel | 1.1 | |

| servos | 0.2 | |

| cables | 0.2 | |

| computer | 0.5 | |

| lift | hydrogen | -9.84 |

| total | -0.14 |

The budget seems feasible, and we even have 140 grams to spare. If needed it can be filled with ballast.

🧩 Pieces

Most of the pieces are off-the-shelf. Some are custom made like the outer shell; and custom carbon fiber panels are expensive. But luckily these panels are mostly one shape. Joining them could be a challenge, and will probably require custom carbon fiber and fiberglass together.

Everything else seems doable by a reasonably well equipped workshop. The gondola does not hold a lot of weight, so might be 3D printed.

🖼️ The Big Picture

To finish this article let’s dig a bit deeper into the concept of a perpetual flying machine.

🤌 But Why?

The first reason why we should do something is always: because it’s fun! Having wild ideas and following their feasibility is always quite entertaining. But it’s reasonable that you might, as I do, feel the need to justify any effort beyond ideation with practical applications.

After publishing the first article I have found a number of references to similar projects; from obscure NASA projects from the 2000s to random posts on Reddit. Let us see what applications they envision.

NASA commissioned a fascinating study in 2003, a concept quite similar to the avis aeterna: an airship supposed to stay aloft for months or years at an altitude of 18 km or higher. The objectives stated are communications and wide area surveillance. In particular it studies how to keep the airships hovering to watch over the US coasts. The concept included fuel cells and an electrolyzer for hydrogen generation. The study doesn’t ask the question of where the water for the electrolyzer should come from, which is intriguing due to the lack of humidity at such heights. It appears to store water somewhere.

The EU has funded the MAAT project, a rather bizarre concept that includes a lighter-than-air platform. It is intended for passenger transportation; although how it intends to keep passengers alive at 13 to 17 km with solar power is not explained anywhere.

Finally, user IsaacArthur proposes to “support some useful communications infrastructure”. And of course there’s meteorological observation like high-altitude balloons do, although to reach high altitude the avis should have to carry more hydrogen and less cargo.

🫴 Scaling Up

This scale model does not have any kind of hydrogen regeneration: it simply does not fit. According to our calculations it doesn’t need it either: surely something else will fail before gas runs out after a million days.

A bigger model should have some kind of atmospheric water gathering, from which it can generate hydrogen by electrolisis to replenish any leaks. A 6-meter-long model will have a height and width of 3 meters, and we get a volume and area of:

V ≈ 3 m × 3 m × 6 m / 2 = 27 m³,

S ≈ 5 × 3 m × 3 m = 45 m²,

W ≈ V × density ≈ 27 × 1.2 kg,

W ≈ 30 kg.In general, given reference length (height and width)

l:

V ≈ l³,

S ≈ 5 l²,

W ≈ 1.2 kg/m³ × l³.With these calculations we are back to gross approximations. Remember that the volume of a spheroid is approximately the cube of its reference length, and that the density is the difference between air and hydrogen, a bit more than 1 kg per m³. With a weight of nearly 30 kg we can do more useful things already.

The law of squares and cubes, or square-cube law, does funny things: a 5m reference length would be 10 meter long, and weigh approximately

W = V × d(air)

W ≈ 5 × 5 × 5 × 1.2 kg = 150 kgNow a usable payload of 10% would get us to 15 kg. These dimensions would be a bit big for a bus.

We don’t have to stop dreaming here: a reference length of 10 meters would take us to over a ton of weight. This kind of artifact might hold a person, should anyone want to ride a dirigible for any reason. The shell might be 10 mm thick. If hydrogen losses remain moderate it might remain aloft for months on end given the right meteorological conditions.

⚡ Max Speed

What will be the top speed of the avis at any length? Let’s suppose

we can lay out half the top rectangle with solar cells that provide 300

W/m², and that are light enough not to tip the avis upside down. This is

currently the state of the art. Given reference length l,

top surface S(top) and generated power P would

be:

S(top) ≈ l × 2l / 2 = l²,

P ≈ 300 W/m² × S(top) ≈ 300 W/m² × l²,This equation yields a max power of 1200 W for our usual model length

of 2 m. Given the drag equation we can find out the required power at

speed v, using the front area and the same drag coefficient

as before of 0.03:

P ≈ ½ ρ × v³ × C(D) × S(front),

S(front) = π × l²/4,

P ≈ ½ 1.3 kg/m³ × v³ × 0.03 × π × l²/4,

P ≈ 0.015 kg/m³ × l² × v³.Combining both equations for power P:

300 W/m² × l² ≈ 0.015 kg/m³ × v³ × l²Therefore we can remove the terms l² from both sides,

and we get a constant equation for max speed v regardless

of model length:

300 W/m² ≈ 0.015 kg/m³ × v³

v³ ≈ 300 W/m² / 0.015 kg/m³

v³ ≈ 20000 Wm/kg

v ≈ 27 m/sWe get a top speed of nearly 30 m/s that doesn’t change with scale. Keep in mind that this is in direct incident sunlight without any inefficiencies, so very likely max speed will be lower than this unless there are major technological breakthroughs. Also we will need some of that power to charge the batteries for the night.

To remain stationary the avis needs a decent average speed to counter any winds. No matter the size, the role of patrolling a given spot is only possible if there are no constant winds in the area. Otherwise the avis will have to navigate those winds by changing altitude or otherwise finding favorable thermal air currents.

But even with a slower average speed the avis may have other applications, as long as it is not required to stay at exactly the same spot.

🔮 Changes

In the last article I used a reference design 10 meters long and 10 meters wide. That is definitely too large for an initial model. The proportions have changed since then.

We have also abandoned the idea of using hydrogen as fuel instead of using an electrical battery. The inefficiencies of converting energy to hydrogen, and then hydrogen back to energy, are high. Also the need to store the resulting water as intermediate product negates any weight advantages.

🤔 Conclusion

It should be possible to create a car-sized model of an avis aeterna, to stay aloft for several days, demonstrating its major features.

🙏 Acknowledgements

Thanks to Carlos Santisteban and Fran Barea for so many fruitful discussions.

Published on 2024-03-16, last modified on 2024-03-24. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.