🔧 On Tooling

🧑💻 With a Focus on Software Development

During my bumpy career as CTO (2019 ~ 2023) I have often struggled to make the case for better developer tooling. For me it was a no-brainer: paying developers a good chunk of money to wait for automated tests to finish, or to do the same change 10 times over in different places, seems like a huge waste.

I have focused on improving the internal workflow whenever I had the chance, even devoting some people full time to the task. But I have often failed to show the value of this investment to (other) company founders: the general opinion was that the dev team were only valuable when working on product features. After all, features are seen as value, while internal infrastructure is at best a necessary evil.

For now I will offer a couple of data points in favor of my position. Some big tech companies (Google and Meta come to mind) are recognized as having great internal toys; this is in large part what enables them to be ahead of the competition. And Joel Spolsky, creator of StackOverflow and Trello, features tooling in several of the points of his legendary Joel Test, used to evaluate the quality of a software team. Specifically point 9 in the list says:

Do you use the best tools money can buy?

Let me make the reasoning now in long form, so hopefully we will all enjoy the benefits of better equipment some time soon.

💰 The Value of Tools

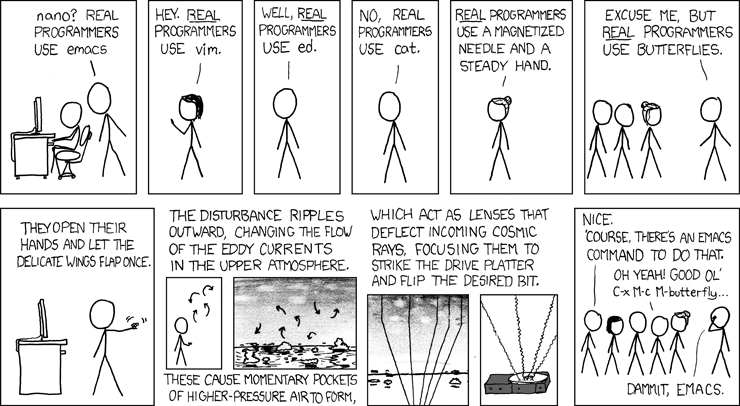

In many professional areas there are almost religious wars about tools. This is even more pronounced in software development, where the arguments between e.g. proponents of the vim and Emacs text editors have been raging on for years. And they are probably more than justified.

Our starting point should not be controversial: the value of work performed by a professional is augmented by the tools they use. A farmer that has to pick potatoes one by one will be 10 times more productive when they employ a potato collector, and again 10 times more when collection is done using a tractor. The value of their work goes up accordingly.

This is, simply put, why the industrial revolution raised the living standards of people. When an employee manufactures 10 times more screws the employer has the potential to pay more, and then this person can go out and spend that money in more valuable goods. It is true that employers tend to want to keep money for themselves as profit. But the knowledge required to operate complex machinery also grows, which is a barrier of entry for other potential employees; skilled operators will demand better salaries. Everyone benefits.

📈 Compound Value

The second derivative is that more productive employers have more money to invest in factory machinery, which in turn improves productivity. As time goes by the quality of the equipment goes up, and this enables the next cycle of investments. With better toolsets in a factory tolerances and clearances will go down, which means that the machines built can be more useful. Precision engineering has allowed us to have millimeter-thick screws and supersonic airplanes and computers. The value of good tools thus compounds over time.

Oh, let me tell you about general purpose computers. In a sense they are the ultimate productivity machines: they can run random commercial programs to do many tasks, and they can be augmented with custom software. Computers can drive lots of different hardware, from weather sensors to industrial printers.

Properly coded programs can indeed control entire production lines. Now we are not only speaking about increasing productivity for one worker, but optimizing entire factories.

🏒 Exponential Value

Can this process of increasing value accelerate even more? Have we found the perpetuum mobile of productivity? Well, up to a point.

In banking, compound interest leads to exponential savings. In our case, compound improvements lead to exponential value. We have to assume that there is some limit somewhere: at some point we cannot optimize a process any longer. The old dream of a single person running a fully automated factory is still not possible, and production is just a single aspect of a company. But when we move to the software industry this limit is even further away. Companies like Google and Amazon showed us that one sysadmin could first herd a bunch of servers, then a rack and at some point a whole data center. Nowadays I doubt sysadmins ever log in to individual servers.

In my mind, the whole point of software startups, hockey-stick exponential curves and hypergrowth is precisely that we are building better tools – for other people or for ourselves. Sometimes for both, as we will see below when we speak about dog-fooding. Uber is in a sense just a productivity utility that matches drivers with riders more efficiently; everything else is financial wizardry to collect the benefits.

Once you are into this frame of mind you will see tools everywhere. For productivity, financial improvement, for better living or just for entertainment; any list of unicorns is just a catalog of more efficient tooling. Google transformed a few categories when they offered better instruments for search, email and targeted ads; Apple is the ultimate hardware toolmaker. And so on.

🧰 Taking Care of Tooling

Let us now focus on internal software: after all it’s what makes us productive to build the next generation of tools. If your toolset is the same as or worse than what your competition is using, how do you expect to do better than them?

🧑🔧 Nice Things

In The Existential Pleasures of Engineering (1976, second Edition 1994), Floorman tells us the great pleasure with which Homer speaks in the Iliad about how various objects are made. There is great pleasure in nicely made tools. We can still get that feeling with a nicely machined computer, and YouTube is rife with videos about people building stuff which are oddly satisfying.

Some people tend to think that good professionals do their best even with crappy tools. Sure, just like in the awesome scene from the movie Rush (2013), Niki Lauda can run really fast in a Lancia Flavia 2000; but he will not be winning any F1 championships any time soon in that tin can.

Would you ask a good butcher to slice a lamb leg with a butter knife? Just as well you might ask a developer to write a web application in a very low-level programming language, like assembler. Good gear is not enough either; you need good professionals to make the best use of them. In my experience they will take great care to choose and maintain their tooling.

They will also strive to keep their working space clean. As my friend Luis Medel narrates in his excellent Spanish article “La martingala del software”, as he was watching carpenters work he was mesmerized by how they always took the time to clean the working area and the power tools they had used.

🦾 Building Stuff

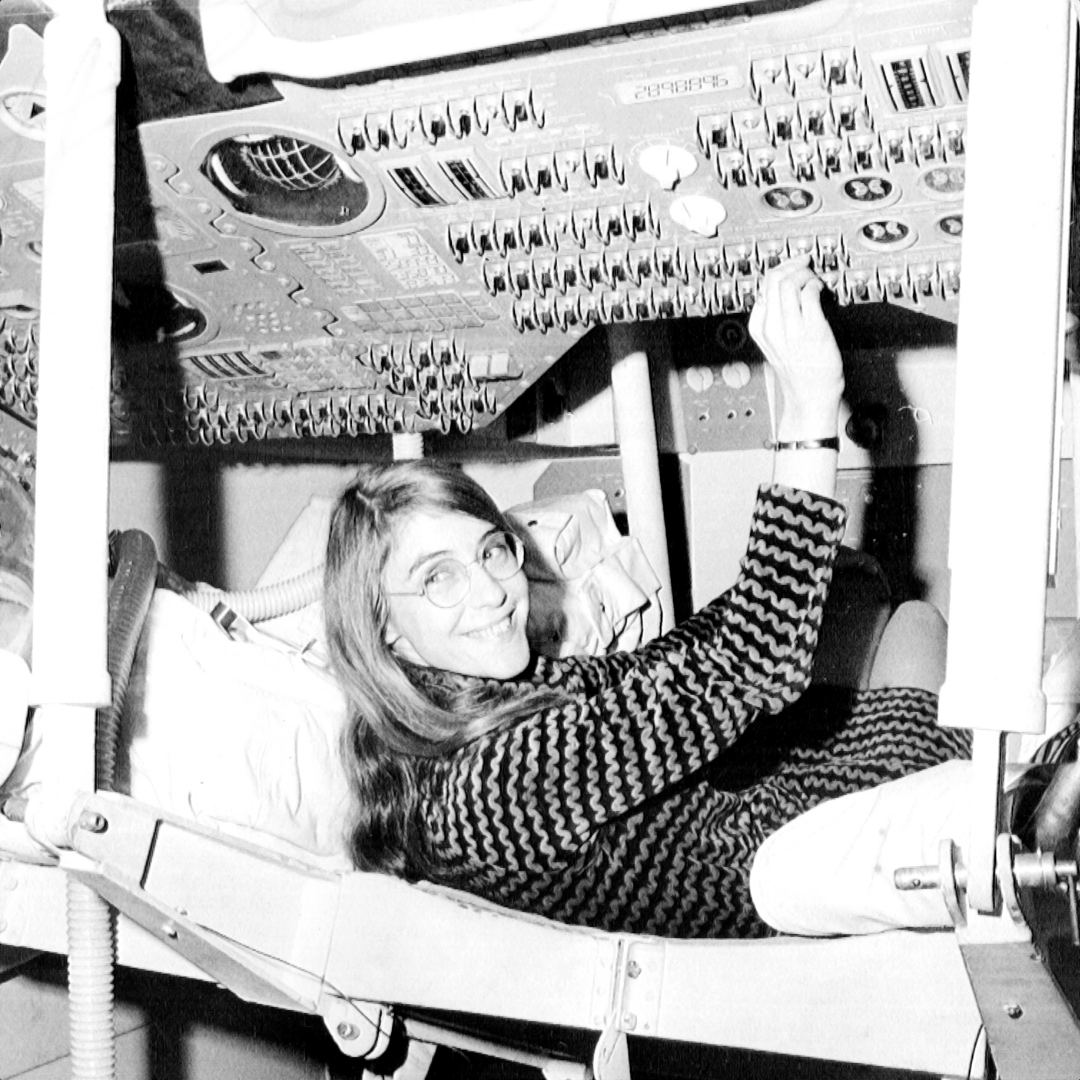

Now if we look at great professionals, they are able not just to pick great tools and take care of them; they can also build their own.

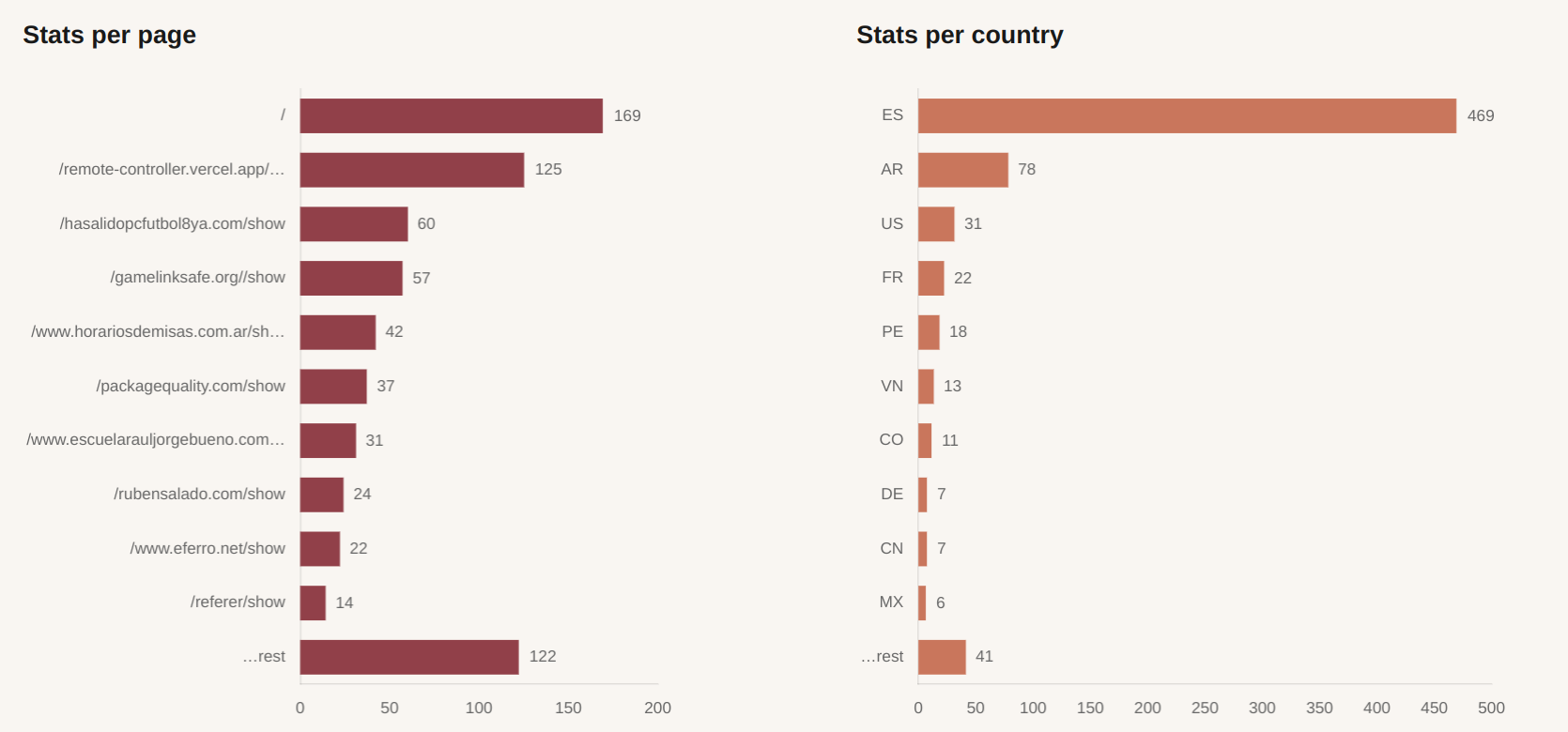

While I don’t pretend to be a great professional, I have polluted the tooling space with my feeble attempts. My mildly successful npm loadtest package has been amply surpassed by the much better AutoCannon by Matteo Collina. I’m still actively working on LibreCounter.org, which is a little package to collect site stats without any of those pesky cookies. I enjoy working on it a lot.

You may be wondering, why build your own when there’s so much stuff out there already? Sometimes you are too early in a space and there are not yet any packages to fall in love with; I started doing continuous deployment using Node.js in 2013 when there were not any good packages, so I built my own pitiful attempt. It worked for us at the time in my company; later on we adopted a better package.

Sometimes you just need something which is too specific or niche. Knowing when to build is an excellent skill to have. Also knowing what to build is important: underengineering is as bad as overengineering, and should be just as infamous.

🧑💻 Software Developer Toolset

In the software development realm we are blessed with a multitude of great tools, thanks to the great developers before us that created them. There are many code-specific utilities: compilers, code checkers (or linters), continuous integration. Learning to use this machinery is essential for a good dev. Luckily the best in class tend to be free software (open source), so in practice they are freely available.

One of the most important arrows in our quiver is the source code

manager, a space that has been dominated of late by git.

Created by Linus Torvalds, one of the greatest developers of our time,

git stores changes as “commits” or incremental

modifications. Care of our working space in this case includes having a

clean git history, and clean branches. A messy piling of

commits and branches is usually a symptom of careless or incompetent

developers. One of my pet peeves is to always stash commits together

every time they are merged (as pull requests or merge requests), so that

it is easy to find out where a change comes from. Also remove branches

once they are no longer needed.

There are many other crucial instruments that ensure our success as devs. Some like monitoring and alerting can be provided by external companies. Others like feature flags are basically techniques that should be used to improve deployments. The most dear to my heart of these is continuous deployment: it allows devs to deploy code to production with every change, many times per day. It definitely changes the relationship with code: it is seen as something dynamic that can be fluidly turned into something else. And it has to be installed and configured to be an integral part of our toolset.

The best way to ensure that these internal utilities are constantly tuned and optimized is to assign them to a developer, or even better to a team. I’ve seen them neglected because they were everybody’s responsibility, and therefore nobody’s. Over time, platform (or similarly named) teams have taken responsibility for internal tooling. While they are not working on visible features, these devs will accelerate everyone else. Their value is therefore not obvious at first, but crucial in the long run.

🗣️ The Tool that Improves Itself

Now let’s take an excursion into a more theoretical area: linguistics and grammar. There is a point to it, I promise, and I hope it will be worth your while.

The ultimate machinery that we have at our disposal is language. As I have speculated elsewhere it must have developed slowly at first as we evolved, and then exploded in a myriad of words.

But not everyone uses language the same way. In particular, philosophy and grammar were born hand in hand. Grammar is, simply put, language turning on itself: people speaking about language. As the great García Calvo used to say:

Language is the only tool that operates on itself.

And consequently we can use it to improve how we speak. This is a turning point in our development as tool makers. Great wordsmiths like Shakespeare have innovated in language: the Immortal Bard created or introduced 1700 words for the English language. While J R R Tolkien created no less than 15 languages for his fictitious Middle Earth.

⌨️ Code as Tooling

Medel’s article mentioned above, “La martingala del software”, made me think how software can be seen as just another tool. And just as any natural language, programming languages can operate on themselves. As such, code is the ultimate machine: it is absurdly versatile and infinitely malleable. A modern computer can handle insane amounts of information, and correctly programmed it can generate any arbitrary output and handle any task. No other human invention compares.

Just as good professionals take care of their equipment, good developers should always keep their code in good shape. A large part of the value of code is in how well it adapts to different situations, and therefore it is our responsibility as devs to make sure we can perform whatever modifications are required, as fast as possible. Code which just grows without any refactoring becomes an amorphous blob which scares any poor souls that venture into its depths.

A very interesting facility that can be implemented using code is testing. Unit, integration and end-to-end tests can be automated, which ensures that any modifications can be performed without introducing new bugs. Having a running test suite (often called CI suite) should be the second priority of any dev team, after keeping the production environment used by customers. No excuses: any failing tests have to be dealt with immediately.

Over time, the success of software as a paradigm has ensured the rise of infrastructure-as-code, which essentially means treating basic infrastructure (servers, operating systems, installed programs) as code with its own repo and tooling around it. It is not just different packages, but a very different framework. The same has happened, to an extent, to data engineering; and more of this is sure to happen in the future: software is, after all, eating the world, and code is a very successful paradigm.

🐕🦺 Dog Fooding

This curious term comes from the pet food industry, where apparently some owners insisted on eating your own dog food. It means that a company that sells a product should use it for everything. The interesting effect is that developers learn the pain that other users have, and become so very interested in improving the tools they are selling. Making the tech team aware of customer pains can be laborious since it’s usually mediated by customer representatives and “customer success” teams.

I learned as much when creating my GDPR-compliant privacy-conscious web tracker, LibreCounter. I used it to see how many people were visiting the site, and what they were looking at. Usually it’s developers checking their stats.

🛑 Too Much of a Good Thing

Not everything is: “let’s go all aboard with tooling”. Let’s see a few caveats about it; most of them should apply to other industries outside software development.

🪀 Shiny Toys

Developers are a particularly capricious bunch when it comes to asking for tooling. We are carried away by the latest shiny things, without regard for their actual utility or proven effectiveness.

Should a CFO comply with every developer request there is likely to be tens of subscriptions to niche programs that are requested, granted and seldom used.

Keep in mind that it is OK to make mistakes sometimes: not everything we get will be exactly what we desire. On the whole we should make sure that most of the tools at our disposal are useful.

🎛️ Overengineering

We spoke above of overengineering: building an overly complex solution for a problem. This can be particularly stinging in the internal tooling area where there are no clear customer requirements.

I have been guilty of this sin many times. Once I built a

git reimplementation in PHP to distribute updates between

nodes, when we were supposedly creating the next platform for tourist

activities. I learned a lot about how git works, but my

efforts were completely misguided when one server would have done the

job perfectly.

You learn from every mistake, I guess.

⛪ The Cathedral

Another related issue is when we attempt to build the perfect solution all on our own: a platform that covers all the bases.

I’m fed up with provider X; let’s build a solution ourselves!

Ever had these thoughts? Feel identified? I know it has happened to me a lot! And from time to time we may fall and get into a major project that never seems to finish.

The worst part isn’t even the scope, but that we don’t deliver value in increments: a cathedral is no use until it is complete. Alas, Google and Meta may have great internal software, but you are probably not Google or Meta. Your scale is not their scale and your needs are different.

We are probably better off building up a series of guerrilla chapels, until we are an established religion with millions of acolytes worldwide. And also we will be able to use them soon!

In my experience incremental building is what makes the difference. Even if we have a whole platform in mind, let’s apply the Pareto principle and tackle the most pressing 20% of issues first. Even if we don’t reach 80% we will have something sooner to make it worth our while.

📹 Keeping Focus

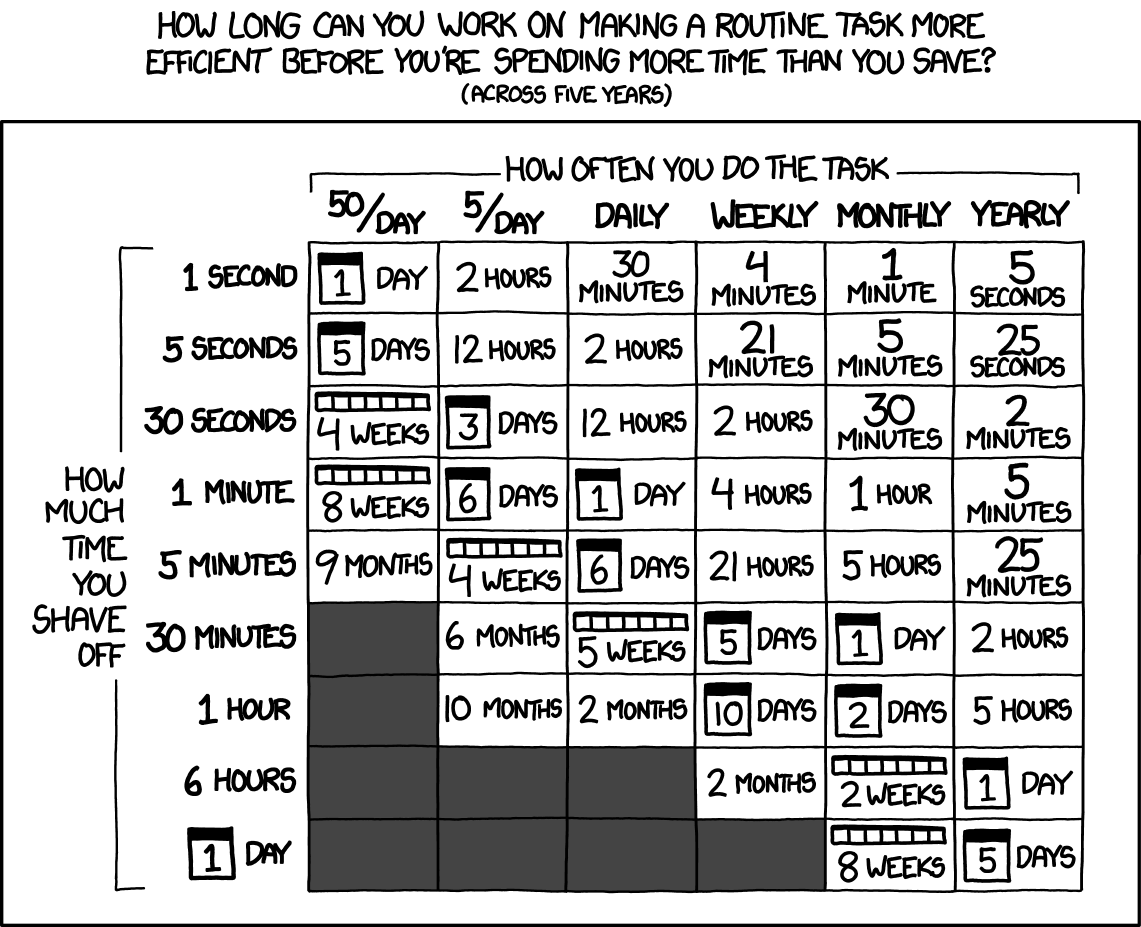

In order to not get sidetracked into unrelated projects, you should keep track of how much time you are really saving, and how long you need to work on something to provide something useful. We would be well advised to tackle those tasks where a few hours of one developer can save the whole team weeks.

Internal tooling needs to be adequate for its use, and the responsible team has to have a clear idea of where the pains lie for the dev team. There is seldom a shortage of work for anyone to do, so pick your battles carefully.

Sometimes we don’t want a particular team to do an internal job; instead it needs to be set a priority for everyone in the company. One particularly interesting area is automated testing: each developer needs to write the unit tests for their own code, and usually also integration tests. In this case the priority needs to be clear: don’t do anything else until you write your tests.

🤔 Conclusion

Tooling is the ultimate investment for a company. If you want to differentiate yourself from the competition start with having the best possible tools. This includes any software required, either purchased or created internally, and streamlining the workflow as much as possible. Features will come easily after that.

Be sure to keep up with the demands from the business side of things. Getting side-tracked or waiting for the next big thing can be the death of a company. Always remember that your toolset is part of the secret sauce that can make you stand out.

🙏 Acknowledgements

I have spoken about tooling with many developers to which I am grateful. Thanks in particular to Luis Medel for the inspiration in his great article, and to Alfredo López Moltó for his insights about caveats. Thanks to Juan Gaitán for his corrections.

Published on 2024-11-07, last modified on 2024-11-12. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.