🫂 The Three Laws of Humanics

On Being Human

Isaac Asimov introduced his famous three laws of robotics in his 1941 story ‘Runaround’. They are supposed to govern the behavior of robotic intelligences. In short form, they were:

- Do not harm humans.

- Obey orders from humans.

- Protect yourself.

🫀 The Three Laws, but for Humans

If you had to sketch three rules to direct human behavior, following the spirit of Asimov’s three laws of robotics, what would they be? I have given some thought to this matter lately. What follows is my best attempt at sketching three sensible rules that may help us take moral decisions.

🏘️ 1: People over Things

The first rule is to care about people over things. Let me tell you a short story, as told by a friend of mine.

A female friend was visiting an American-Japanese girl in their family house. While she was there the mother of the family was cooking all their meals, tending to their needs and caring about them in general. Whenever they came home everything was ready for both of them. My friend noticed the house had an amazing Japanese garden, perfectly cared for. She asked the mother:

‘That garden is awesome! It must take a huge effort to care for it.’ ‘Yes’, replied the mother: ‘at least four or five hours a day’. ‘I don’t understand’, my friend replied. ‘You take care of us all day long. How do you manage to tend to the garden as well?’ ‘There is no mystery: people should always take priority over things. I will take care of the garden once you leave.’

This story is probably apocryphal: my friend has later said she has no recolection of the matter. But it illustrates the point well: people are the most important aspect in our lives, and they should take priority over everything else.

🤗 2: Take Care of Those Closer to You

The second rule is take care of people closer to you before others. This may sound egotistical or outright selfish. However the opposite would lead us to very weird behavior, which we can see sometimes and which some find admirable, but I don’t think faciliates a sane society.

Consider the life of the biologist George Price, as narrated in Tim Harford’s podcast The Man Who Solved Kindness. From Wikipedia:

[…] he began showing an ever-increasing amount (in both quality and quantity) of random kindness to complete strangers. In this way, he dedicated the latter part of his life to helping the homeless, often inviting homeless people to live in his house. […] He also gave up everything to help alcoholics; yet as he helped them steal his belongings, he increasingly fell into depression.

In fact Price had discovered an equation that showed how animals are more likely to help their kin, as they carry part of the same genetic material. This is sometimes called genetic altruism. However in humans this is not so clear cut; the biologist precisely wanted to show that human altruism is above all this gene stuff. Meanwhile he was overlooking his family and friends.

For another counterexample let’s look at what the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau did with his five children: he sent them all to an orphanage, with the idea that they would be better educated there. Meanwhile his writings were enlightening the French society of his time, but his behavior to his close of kin looks profoundly despicable.

Suppose we took care of everyone in the same degree. This would definitely mean that we overlook our family and friends, and indeed anyone that has helped us in the past. In a perfect world perhaps we would all get what we need. In practice just a few rotten individuals would spoil the whole system, getting the benefit but not doing the work. Also we would be unable to keep any friends or family, or any safety networks that we build with our care and effort. Probably not good for our mental wellbeing.

Another terrible take is effective altruism, whose proponents sometimes prioritize the welfare of distant future generations rather than people in our own time. This is another way of ignoring our fellow people, which we know, for remote descendants, from whom we will certainly learn nothing about.

In short: if you want to have people close, the best recipe is to care for them.

🐤 3: Protect the vulnerable

The third rule is quite succint: protect the vulnerable. This most important rule of being human is what makes us keep our babies alive, our sick tended for, our elderly live long happy lives, and in general lets us be decent human people.

I don’t think this point needs much justification. The opposite would be “don’t take care of the vulnerable”, which has distinct nazi vibes. “Survival of the fittest” is good enough for animals in the savannah and for finches in the Galapagos; but hardly a principle for humans to live by in society.

📋 Using The Three Laws

The aim of these three rules is that they should help us make better decisions, and in the process make us better people. I have started using them almost daily, especially the first one. Whenever I’m glued to a screen, no matter how interesting it is whatever I’m doing, and someone asks me anything I remind myself: ‘People over things’ and pay attention to them. (Except if it’s work I’m doing, in which case I am actually helping my colleagues and indirectly also my family.)

About the second rule, caring more for closer people: it can be quite useful when living in society, where many worthy causes fight for our attention. It does not mean that you don’t care about those that are not as close; if your close people are well enough then it’s probably time to help more distant friends and relatives. There is a lot of leeway here that has to be solved case by case.

The third rule can help me decide if (and why) I should care about children in need, or speak to frail old people that get happy when you talk to them. I also believe it can make us kinder to disfavored people in society. Perhaps that convicted criminal just had a bad start in life and just deserves a fresh start. Or maybe that homeless person only needs attention and an opportunity.

🤖 But We Are Not Robots

Of course we are not robots, and that is why I’m speaking about “rules” rather than “laws”. (The title would not be as catchy though.)

All of these rules cannot be applied blindly; they must be qualified. A few questions will surely pop up in your mind, which can help us start the discussion around what the rules mean to each of us. As you will see below I have my own answers, but I think part of the fun is figuring out on our own what we believe and what we stand for.

What is “people”? Where do animals stand?

This one is easy: people are other humans, technically specimens of Homo sapiens. Not animals, not primates, not even bonobos or chimpanzees.

Perhaps if you are an animal lover you can think: “people over animals over things”, and that is fine. Perhaps you even think: “I prefer some animals to people”, and that is where I can tell you that we definitely disagree. People should always take preference.

Once we have really intelligent robots they should probably still be considered as things. Things are not a substitute for people, and they cannot be.

What does “closer to you” mean?

Does “closer” mean family, friends, colleagues, people from your home town, people with the same interests?

Observe that I am not qualifying this idea; but we all know what “close” family is, what being “close” friends means, and that sometimes friends can be closer than family. I find it interesting that we have a shared feeling of “distance” with people, that allows us to determine who is close and who isn’t.

To what degree should we care more about closer people?

It would be nice to be able to graph closeness for everyone and the degree to which we should care for them: x for siblings, y for parents, z for cousins and so on. But we are fallible people: the only rule is that closer people get more attention, but it does not stop at any point: remember, even very distant people are above objects.

Who are “the vulnerable”?

This category is not easy to define. Does it include minorities, protected classes, people mistreated by society? Intersectionality would suggest that people in multiple discriminated categories would deserve better treatment.

I am not going to even attempt to define who is more vulnerable and who isn’t. This is part of the discussion that needs to be had.

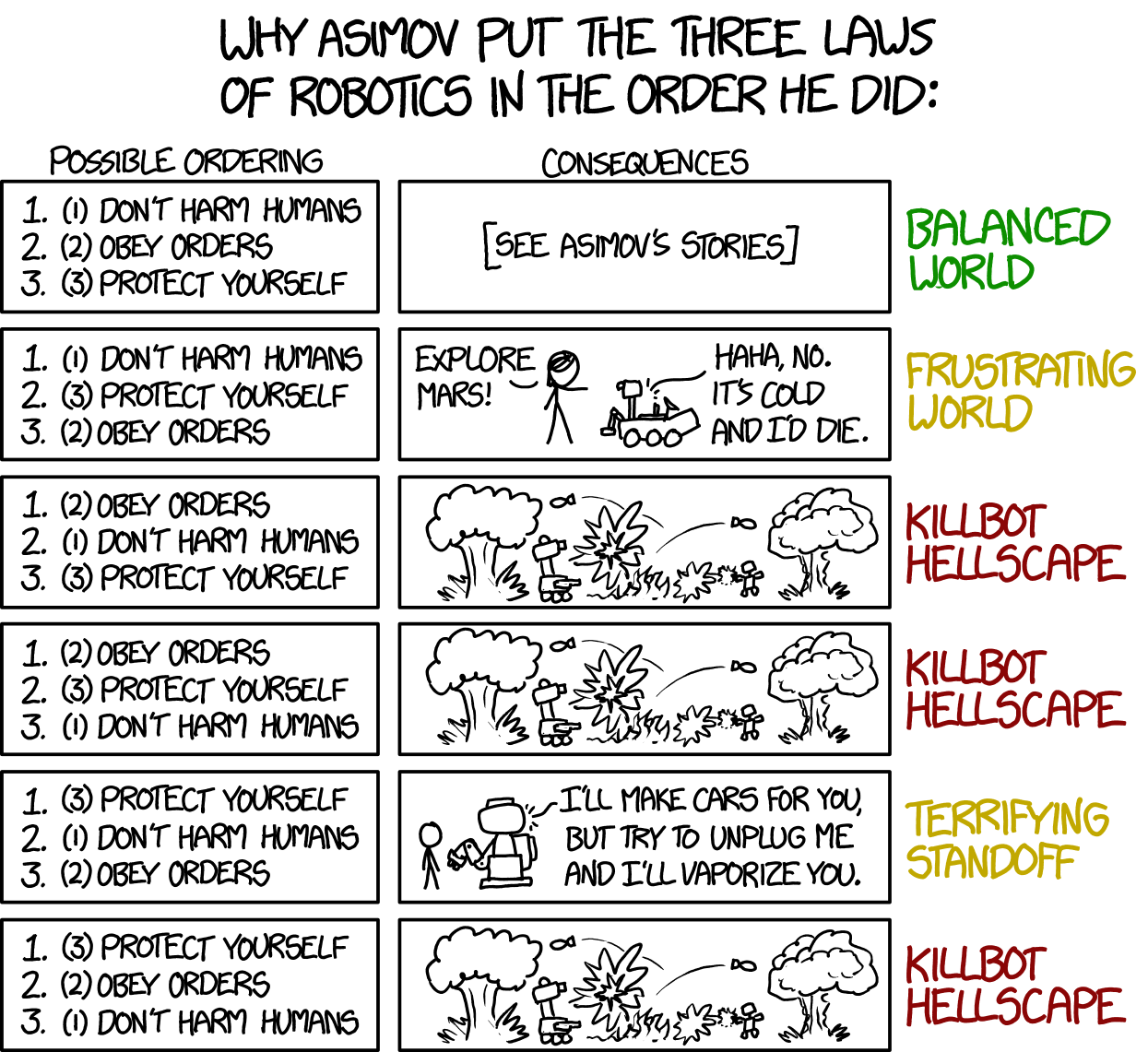

Priorities

Another apparent subtlety for applying the rules is even more important. What priority should each rule take? Asimov’s laws of robotics must be followed in order, i.e. the first law takes priority over the other two, then the second over the third, and finally the third.

In our case the priorities are not so clear, especially between the second and third rules. There has to be a balance involved in every decision. Should I spend one euro more on something for me, for my family, or to help Ukranian children, innocent victims of war?

The better part is that we have a baseline, a criterion that needs refining, a calibration to perform. Our decisions will never be perfect, but we can try to do our best.

🤔 Conclusion

Having a set of rules to help us make decisions is important to keep our sanity in these turbulent times. They may help our judgement, but will never replace it.

🙏 Acknowledgements

Thanks to my friends and family for the interesting discussions around this issue, and for the ones I hope to have in the future.

Published on 2025-09-08, last modified on 2025-09-08. Comments, suggestions?

Back to the index.