🌐 Flying Around the World in under 80 Days

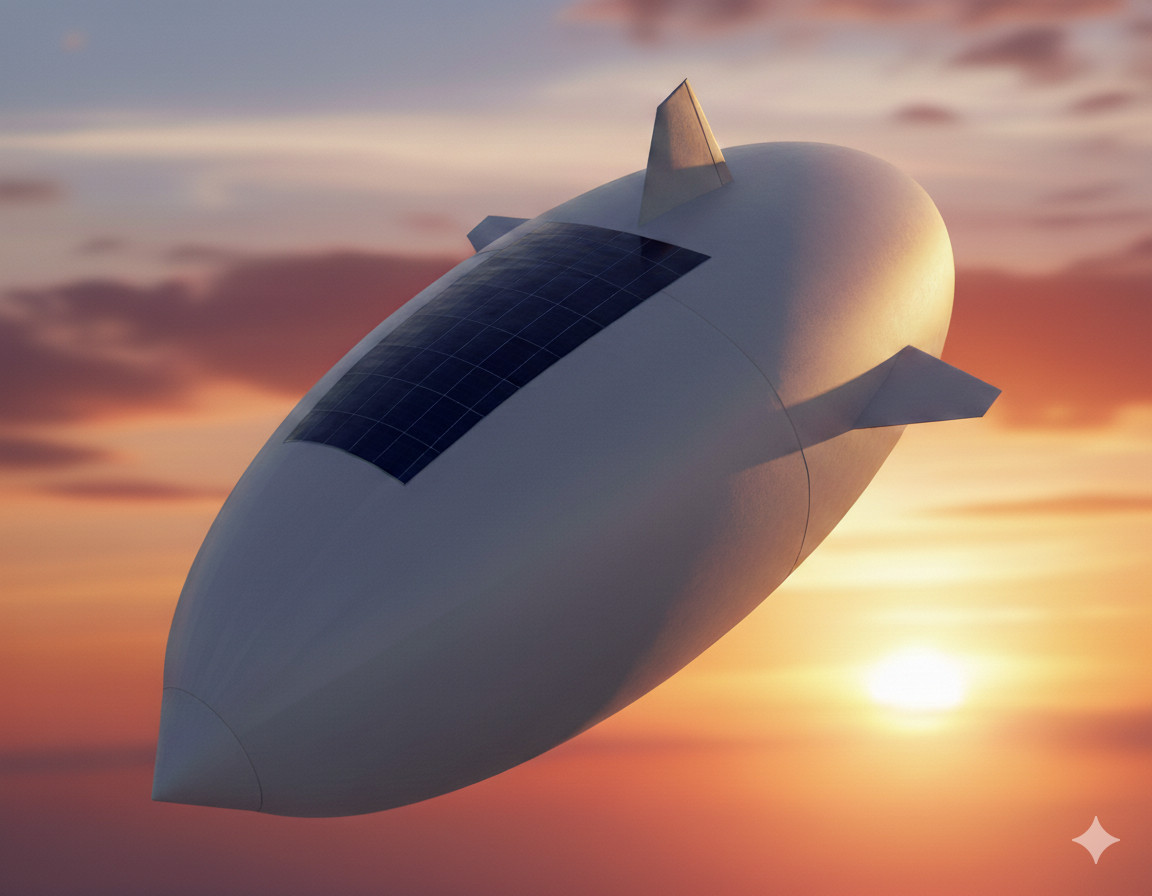

Avis LXXX: an Autonomous Airship Drone

Is it possible to complete a trip around the world with an autonomous drone? And under 80 days? Today we will explore this crazy project that would make Jules Verne proud. And we will try to figure out if it can be done with a relatively modest budget.

🚧 The Project

For starters let’s review how crazy the idea is by answering a few questions that may be popping into your head.

How fast does it need to go? First, we want to build a flying device that can autonomously circumnavigate the world in less than 80 days. If it went on a straight line around the equator the trip would take 40,000 km, or 25,000 miles; in 80 days average speed comes out as a little bit over 20 km/h (13 miles/hour). In what follows we will use meters per second; so 6 m/s will be our minimum speed target. Let’s make it 10 m/s to have some room.

Can we make flight more efficient? The biggest energy expense for a drone is usually not moving about, but staying up in the air. For our little project it will need to keep running for many weeks. One solution I’m particularly fond of is making the aircraft buoyant on its own. An airship can remain afloat as long as it holds its lighter-than-air gas inside. The obvious solution is to propel the drone using electric batteries, and replenish the power during the day using high efficiency solar panels.

What is the best option for the gas inside the airship? Helium is the usual choice, but for a drone where no human lives are endangered it may not be optimal. Hydrogen is cheaper, lighter and more readily available. Any risk of conflagration can be mitigated by careful construction.

What kind of enclosure is needed to hold the gas inside for 11 weeks? This was solved more than a century ago with clever construction, and modern materials make it even easier. The enclosure can be made strong and resilient while keeping it light by using composite materials. There are readily-available polymers with low hydrogen permeability such as PVA or EVOH, and they can be supplemented with other layers that prevent ultraviolet damage and weather corrosion.

How big does the airship need to be? Ship size is a critical parameter. A small drone is easier and cheaper to build, while bigger ships tends to have higher top speeds. Having enough instrumentation onboard also requires to carry a minimum payload. We will set a target length of 4 meters and check if it works.

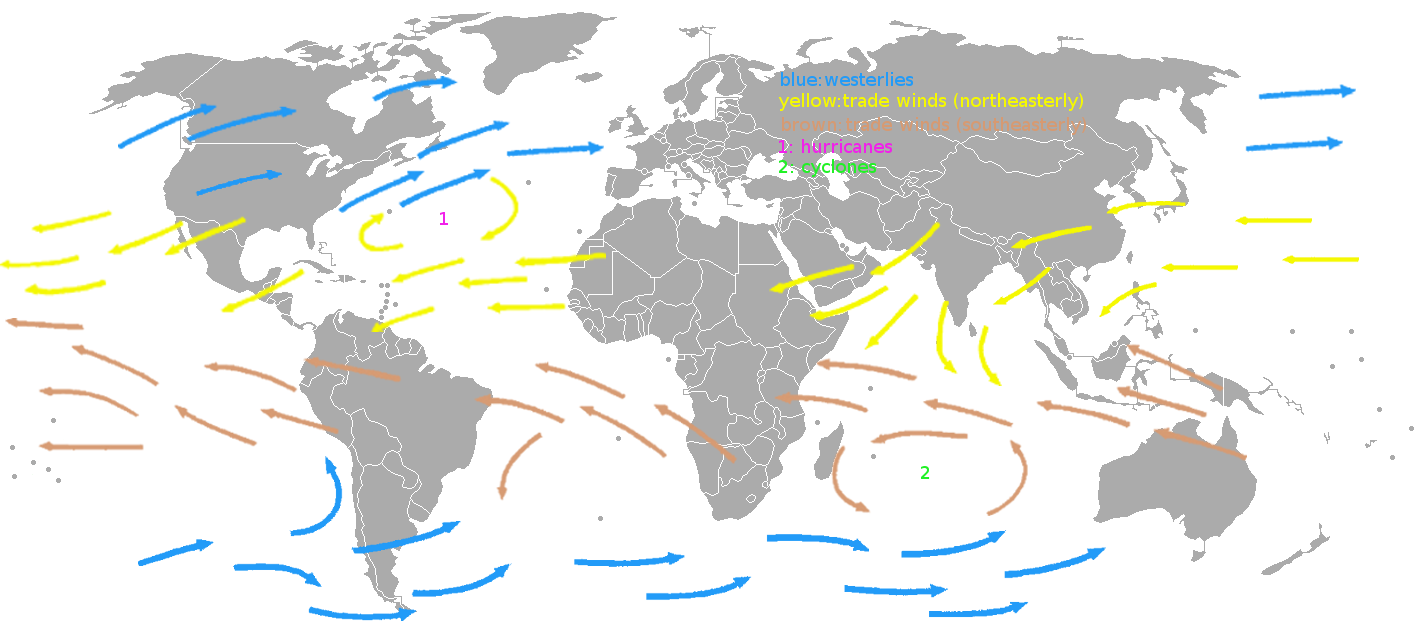

What is the best route to take? An airship can also helped by trade winds: air currents caused by the rotation of the Earth that move on average from East to West. The trajectory should therefore follow this orientation rather than West-East. A modestly sized airship cannot go against strong air currents, so the path should be carefully planned in advance and adjusted while in flight, to take advantage of the wind at every point.

Finally, can it be flown legally? Most of the trajectory can pass over the oceans, but skipping land completely would take too much of a detour, and likely be incompatible with prevailing winds. Although the political climate may be hostile, it is still legal to fly civil craft over other countries. The challenge here is to find some convenient low-hostility routes for safe passage.

💡 Concept

The inspiration for reliable hydrogen airships is quite old. More than a century ago the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo came up with the Astra Torres designs, autorigid dirigibles which were used successfully in the Great War. Unlike the competition from German Zeppelins and others, these hydrogen monsters had no flammability issues at all during their long career, due to careful design and construction.

Solar panel advances are very well exemplified by the Airbus Zephyr, now run by its own company AALTO. In 2025 it endured 67 days of autonomous powered flight, recharging during the day and hovering during the night. The efficiency obtained by their batteries and solar panels is awesome, and there are now consumer products in the same range.

🛩️ The Craft

Let’s now review the details concerning airship design and construction. Keep in mind that everything we say here will be a bit handwavy, just intended for a very preliminary feasibility study. A large part of the project is proper engineering research into how to make the project work reliably, and how to fly autonomously for weeks.

📐 Size

Thanks to the latest advances in miniaturization a drone can be quite small, while still being fully functional. We will set a target size of 4 meters, which we have previously analyzed in Aves Æternæ. Minor axes are 2 meters long; surface is 21.48 m² while volume is 8.38 m³. This gives us a max weight of less than 10 kg. We will review and update these specs for the trip around the world.

How much gas do we need for this mission? A spheroid of 4x2x2 m³ will use around 560 grams of hydrogen, which occupies 8 m³ of gas, or 8000 liters. This may seem like a lot, but it is almost exactly the contents of a commercial hydrogen cylinder.

📍 Outer Shell

The airship cover needs to keep its shape and endure the elements; while being light enough to stay within spec. I previously assumed that a carbon fiber skin was the best option. This was a bit misguided: the material is too rigid, too opaque and not resistant enough to withstand the elements. A composite skin of different polymers seems like a much better option, with an external exoskeleton of carbon fiber to keep its shape.

The exact composition needs to be studied, but it must deal with:

- Tensile strength: be able to withstand strong winds and changes of pressure. Polyurethane seems to be a good choice.

- Ultraviolet damage: keep up with the strong sun near the equator.

- Water resistance: endure rain for extended periods.

To build the outer shell we need to join a number of pieces with funny shapes. I did some numerical integration for the Avis Minima project, to find how to divide an airship into four planar segments. These pieces can be joined together using ultrasonic plastic sealing, which is much more effective than traditional sewing techniques.

I have found that it is a good compromise to use around half the weight of the airship for the external envelopes. Preliminary numbers show that 3 kg should be enough for the outer shell; for our surface of 21.5 m³ we get an areal density of 140 g/m². If you know your paper qualities, this would be equivalent to thin cardboard. For light polymers that have a density around 1 g/cm³, this gives us a thickness of 0.185 mm.

🎈 Hydrogen Gas

Additionally, a gas bag will be needed to hold the hydrogen for extended periods. Judging by the literature a target of 1% leakage per week is quite doable. For instance in this article, or this commercial provider that advertises 2% helium loss per week.

Losing 1% per week for 11.5 weeks (80 days) would leave us with 11.5% less gas at the end of our little trip, which can compromise buoyancy by reducing lift by more than a kilogram. Smaller leakages or a shorter trip (see below) may be necessary. Keep in mind that hydrogen is a smaller atom than helium, but a bigger molecule as there are two atoms. I have not seen a definitive answer on which gas is easier to contain, but there have been considerable efforts to contain hydrogen since it is used widely in industrial settings. It seems that polymers such as PVA or EVOH are best suited for containing it.

We should be able to spare 1 kg for the gas bag; again for our surface of 21.5 m³ we get an areal density of 47 g/m². This corresponds with very light wrapping paper or thin supermarket bags. Since PVA is 1.19 g/cm³, this gives us a thickness of around 40 microns, which is common in the industry.

🪽 Structure

We also need a strong carbon fiber structure to keep everything in place. We will reserve 1 kg for a few strips of carbon fiber around the structure, three little wings (one on top and two on the sides), and a nose cone. The strips are aproximately 26.5 meters long, if maths serve me right; making them 0.5 kg would give a length density of 18 g/m, although it is probably better to make the top strips lighter and the bottom strips sturdier. The wings and the nose cone are a bit over a square meter, so an areal density of 500 g/m² seems appropriate.

It remains to be seen if the structure can be made lighter to save even more weight.

🔋 Power

Our target speed of 10 m/s requires some serious power. With the drag coefficient of 0.03 computed in Aves Æternæ we get a general formula of:

P ≈ ½ 1.3 kg/m³ × 0.03 × 3 m² × v³,

P ≈ 0.06 kg/m × v³,So in order to reach 10 m/s we need:

P ≈ 0.06 × 10³ W,

P ≈ 60 W.Let’s set aside a power target of 165W, so we can drive our motors while charging the batteries at the same time. Using commercially available solar cells 224 W/m² is currently achievable, with a weight of 384 g/m² (cells only). We can reach our target of 165W with an area of 0,73 m². Building a solar panel requires giving the cells some support, protection from the elements and electrical connections; let’s suppose a total density of 1 kg/m². Just to be safe we will use a flexible panel of 1 m² weighing 1 kg, which should fit comfortably on top of the drone. This gives us the full 224 Watts.

And we may as well need this kind of power. Power requirements grow with the cube of the speed, which is a lot. What happens if we use the full power to run the motors? 224W with an efficiency of 90% would allow us to reach peak speeds of 15 m/s (54 km/h or 34 mi/h):

P ≈ 0.06 × 15³ ≈ 202 W.This could be used for emergency situations or to counteract strong winds. Maximum power is only reached with full-on sun, which can be reached at most during a couple of hours per day, so we need some margin. And 90% efficiency may be a bit optimistic.

Storing all this energy can be costly. Energy density for LiPo batteries can reach 200 Wh/kg, so if we use a 1 kg battery we can store up to 200 Wh. This would take a couple of hours to recharge if we can spare 100 W. At night it would be able to give 20 W for ten hours, which would result in a speed of around 6 m/s.

P ≈ 0.06 × 6³ ≈ 13 W.Depending on how many hours of direct sunlight we get, our little airship might be making around 500 km every day:

- Day: 10 m/s for 8 hours = 288 km.

- Night: 6 m/s for 10 hours = 216 km.

- Total: 288 + 216 = 504 km.

So even without wind we are almost at 80 days around the equator!

💻 Completing the Build

Some years ago it would have been hard to find lightweight motors and propellers for a smallish airship such as the Avis Lxxx. Luckily for us, recreational drones exist! Nowadays we can get awesome combinations of motor + propeller that weigh less than 50 grams, bringing the total weight to 100 grams. For instance this brushless motor weighs 37g and can give as much as 270 Watts, while these propellers are just 8.8g.

Navigation computer and communications equipment can be similarly miniaturized, and again can be below 100 grams. Both can live inside the gondola where they are protected. What about the gondola itself? The bottom does not need to be particularly strong since it will just hold the weight of the battery and electronics. The sides will hold motors + propellers, with enough distance to avoid hitting the enclosure. I am envisioning a boat-like structure with a length of 30 ~ 50 cm, a width of 20 ~ 30 cm, and height of ~ 10 cm. Hopefully it can be lightened to around 100 grams.

We also need a certain length of cable to connect the solar panel to the battery: around 6 meters, which is the perimeter of the enclosure at its equator. 16 awg cable (< 100 grams) should be enough.

⚖️ Weight Budget

Our combined weight is at this point:

| Component | Material | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Enclosure | Composite polymer | 3 kg |

| Gas bag | Polymer | 1 kg |

| Structure | Carbon fiber | 1 kg |

| Battery | LiPo | 1 kg |

| Solar panel | Composite | 1 kg |

| Gondola | Polymer | 0.1 kg |

| Motors + propellers | Polymer + metal | 0.1 g |

| Electronics | Metal | 0.1 g |

| Cable | Copper | 0.1 g |

| Gas | Hydrogen | 0.7 g |

| Total | – | 8.1 kg |

An 8 kg airship will certainly be able to float. Remember that lift is due to the volume of air displaced by the hydrogen, so with our 8.38 m³ lift will be:

L = 8.38 m³ × (1.3 - 0.070) kg/m³ ≈ 10.3 kg.So we still have more than 2 kg to spare, right? But air density of 1.3 kg/m³ is only reached at unrealistic temperatures of 0 °C! As temperature raises air becomes less dense, so we will get less and less lift:

| Temperature (°C) | Density (kg/m³) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.3 | 10.3 |

| 10 | 1.25 | 9.9 |

| 20 | 1.2 | 9.5 |

| 30 | 1.16 | 9.1 |

| 40 | 1.13 | 8.9 |

The budget is getting tighter, and we are still at sea level. The airship will have to go over land at some point, and keep a certain height to have clearance over any terrain elevations. Air density decreases fast with altitude: the international standard atmosphere dictates that at 500 m it will be down 5%, so we will have 0.95 of the lift: at 30 °C it’s only 8.65 kg. But this is just the average! Poor weather also brings down atmospheric pressures, and therefore reduced air density. We don’t have a lot of weight to spare now, do we?

The last factor is hydrogen loss: even at 1% per week, after 80 days there will be 12% less gas, and this space inside the enclosure will be occupied by air. Lift at 500m and 30 °C is now down to 7.6 kg. In fact, according to this handy density calculator our little airship would hardly be able to keep airborne at all! So one of the challenges is to reduce hydrogen losses, or make a faster trip, or save even a few grams here and there. At this point the weight obsession of airship designers starts to be understandable.

On the other hand, size works to our advantage. In particular, just elongating the structure will increase lift while keeping the rest of the project mostly intact. Another option is to just increase all the dimensions: thanks to the square-cube law, a 10% increase (to 4.4 meters long) will increase weight from 8.1 to 9.8 kg, while lift will go from 8.1 to 10.8 kg. Cost and complexity will likely also go up, so there is a sweet spot in there somewhere.

🗺️ Navigation

What scenic routes will we take across our beautiful planet? We have to consider a few key points:

- Go as straight as possible.

- Take advantage of winds.

- Not get shot at.

👣 Route

We might think that the best path is to go in a straight line curved around the globe. The diameter of the equator is 40,000 km, and if we just stay on the 40°N parallel it is even shorter: 30,000 km. But this is not very efficient.

As we saw before we need the help of trade winds, which usually blow from East to West. They can help us shorten flight time: average trade wind speed is 5 m/s, which combined with our computed speeds:

- Day: 15 m/s for 8 hours = 432 km.

- Night: 11 m/s for 10 hours = 396 km.

- Total: 432 + 396 = 828 km per day.

Much better than the 500 km per day we were getting before. If we assume that our route is 50,000 km long, we would be in the air for 60 days, or under 9 weeks.

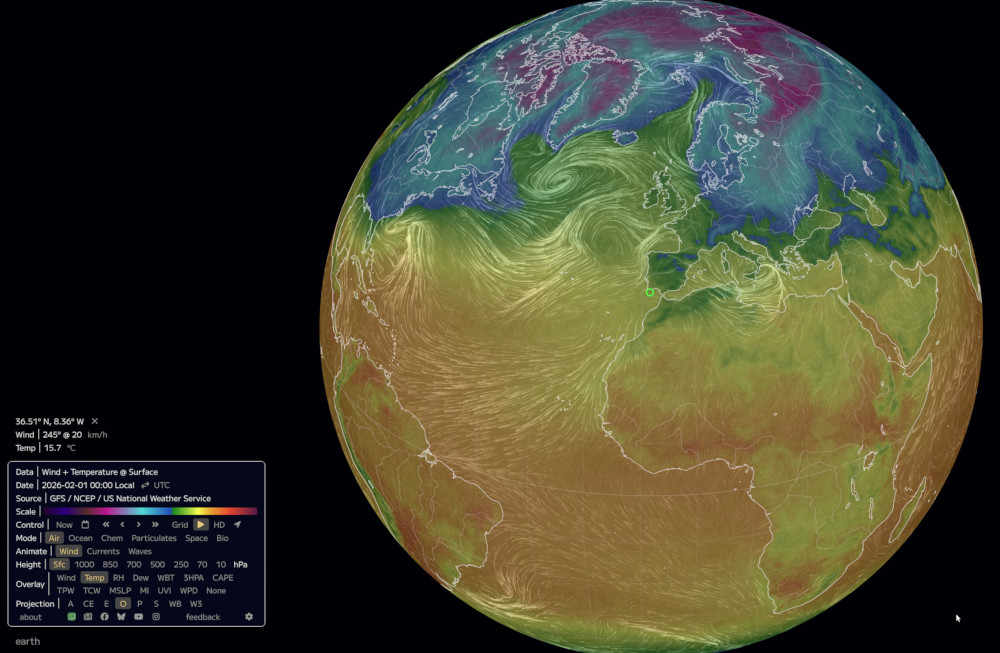

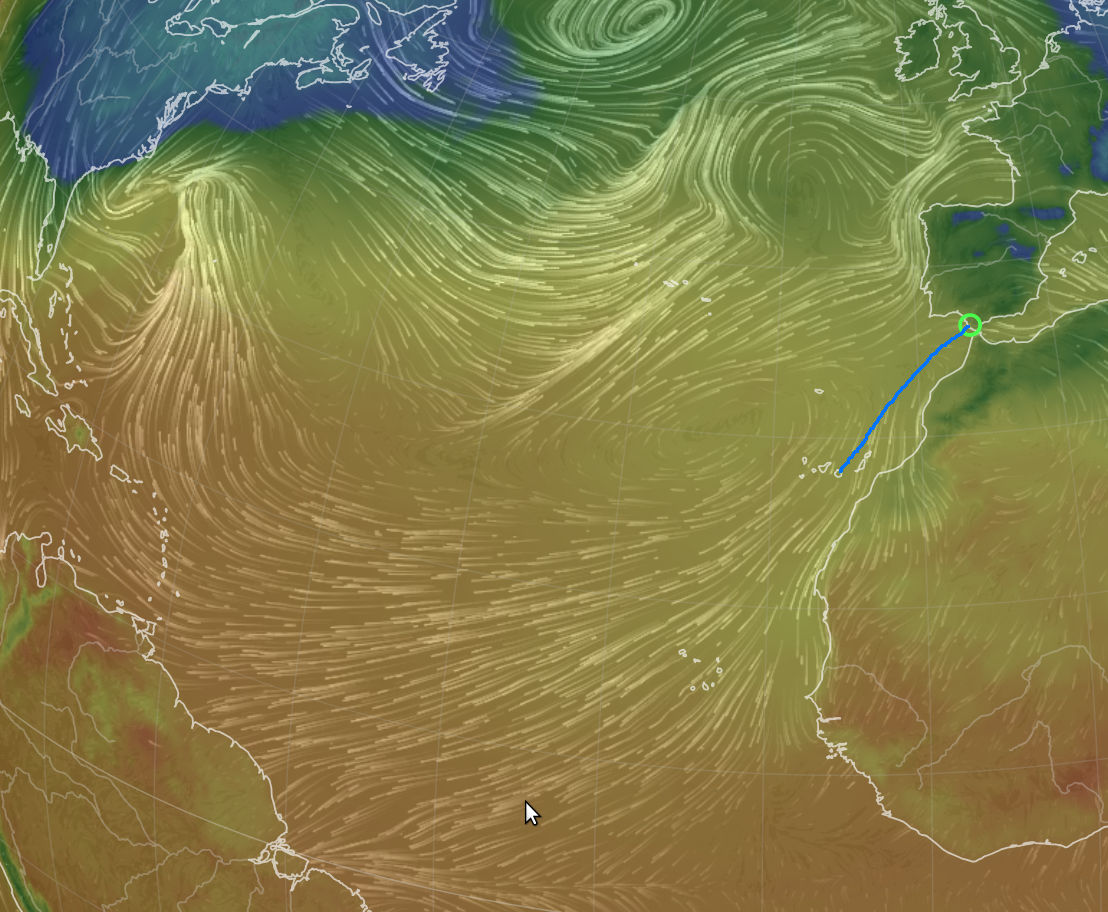

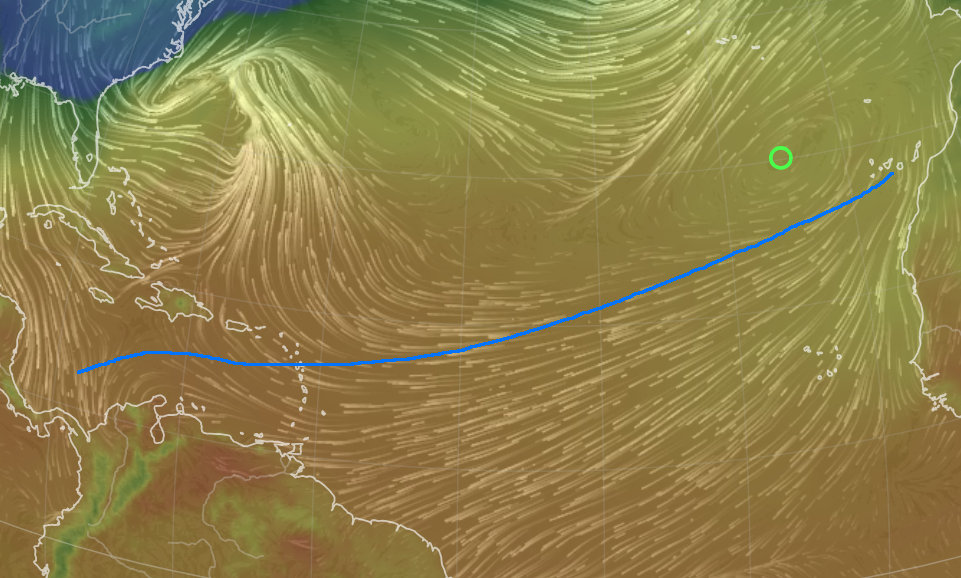

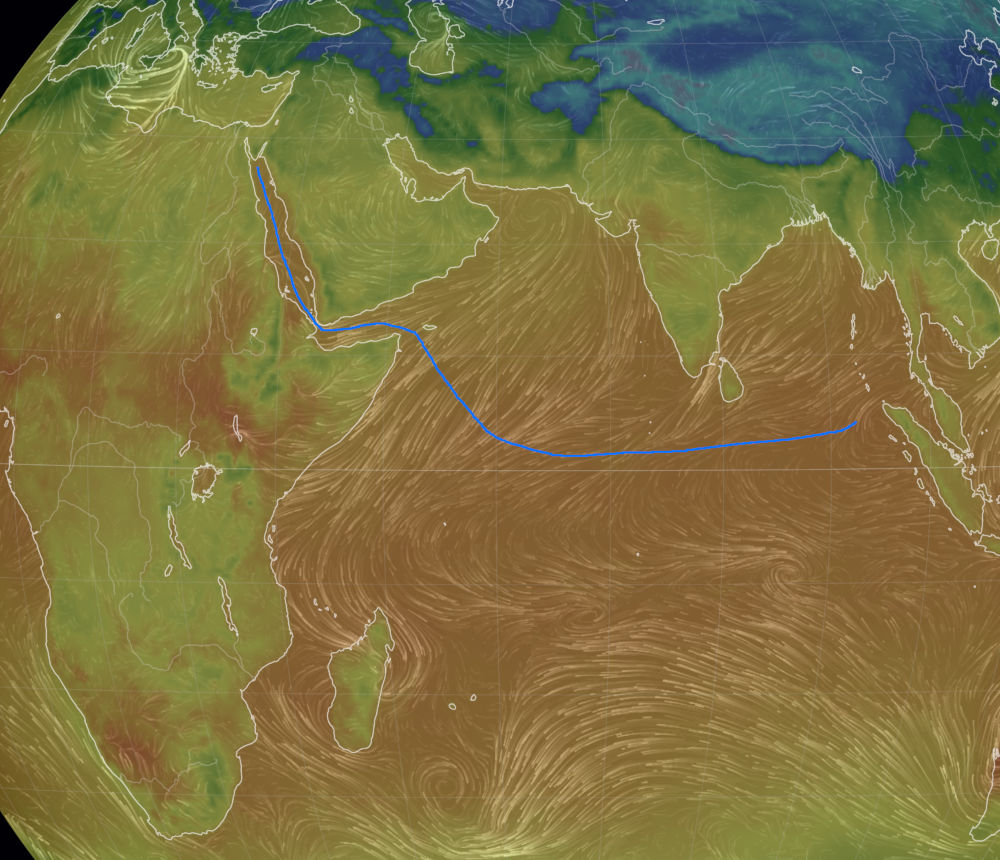

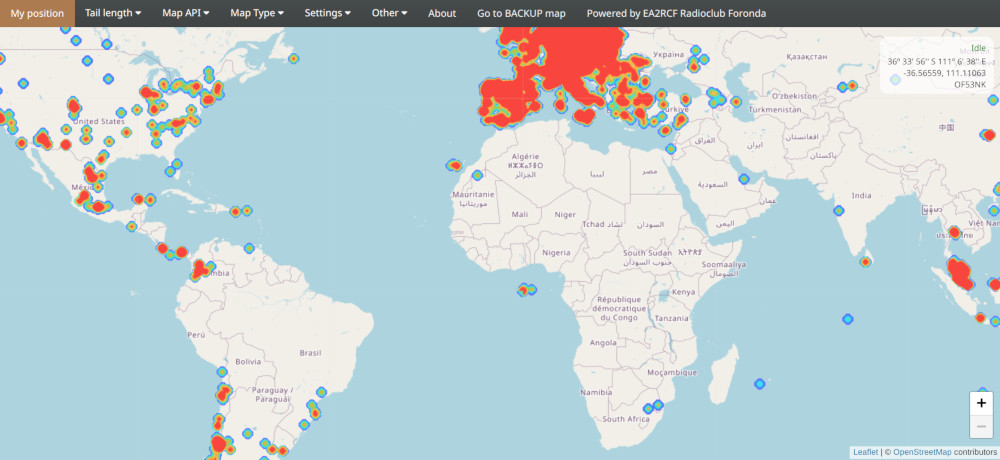

Head winds should not surpass 13 m/s if we want to be able to counteract them. 49 km/h (30 mi/h) is not a lot, especially over sea. The wonderful nullschool earth project will help us a lot in this imaginary flight plan.

🛄 The Journey

A convenient starting point is in Southern Spain, near Cádiz. The prevailing winds will usually help us get to the Canary Islands. Keep in mind that wind conditions change all the time; we are depicting the weather on a typical winter day, as cold helps us get denser air.

From there winds do really help us move West, on this particular day at almost 10 m/s.

Now we need to cross the Americas. We also need to avoid hostile countries, or places with itchy triggers against flying things.

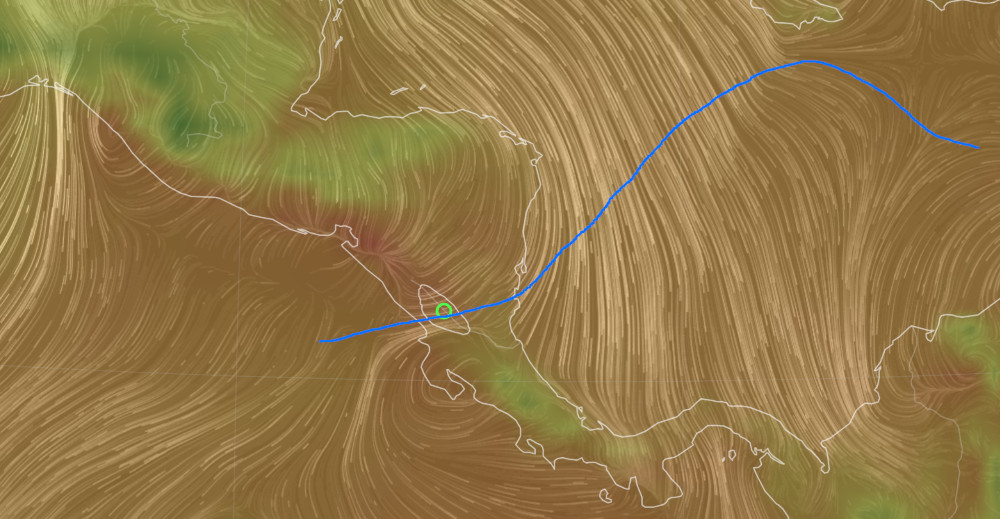

By a lucky coincidence there is a very convenient place where the wind will help us make it through: Lago Cociboica (also called Lake Nicaragua). The almost constant winds always blow East to West and will help us push through.

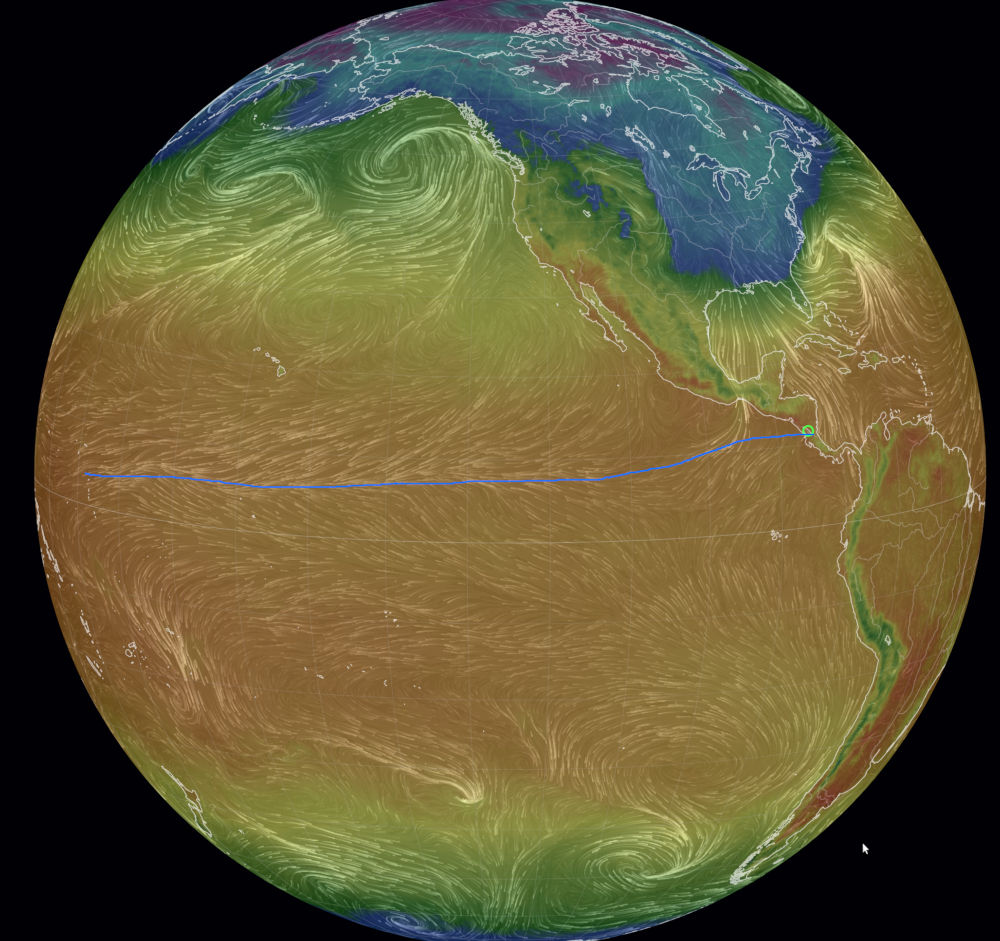

Now we are up for the Pacific journey, the longest leg of our trip. We have to cross a vast expanse of ocean 16000 km long.

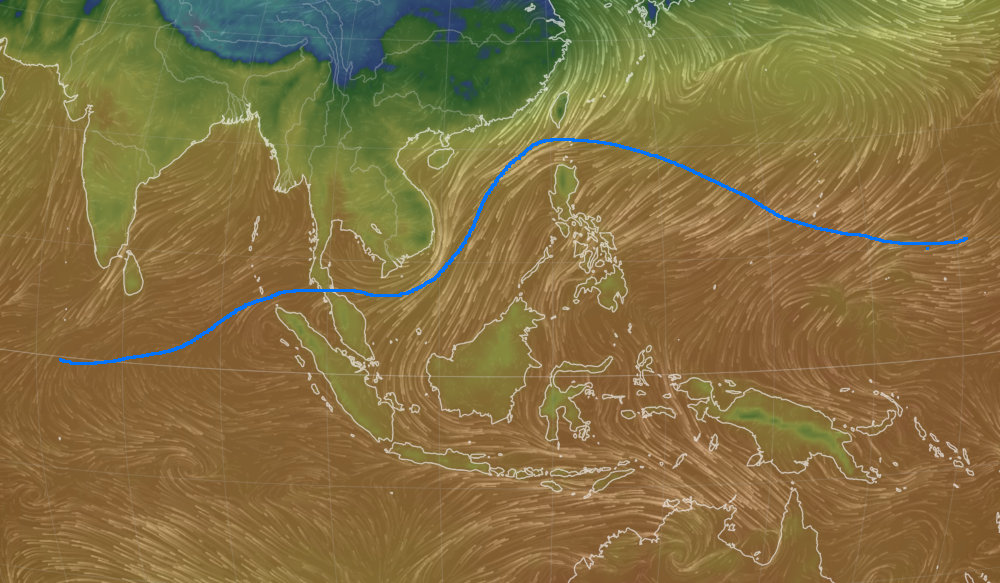

Next we have to cross Southern Asia. There is no path completely over land which is practical against the wind, so we have to cross over at some point. Preliminary analysis shows that we could cross over Thailand, near the border with Malaysia.

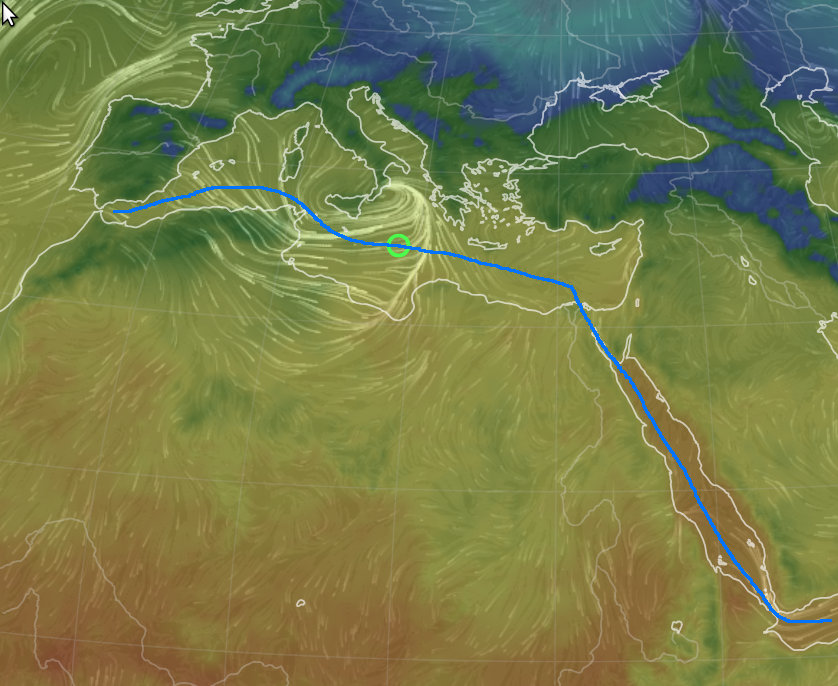

Next we cross over the Indian Ocean, and move near Africa. The shortest path seems to be to go over the Red Sea.

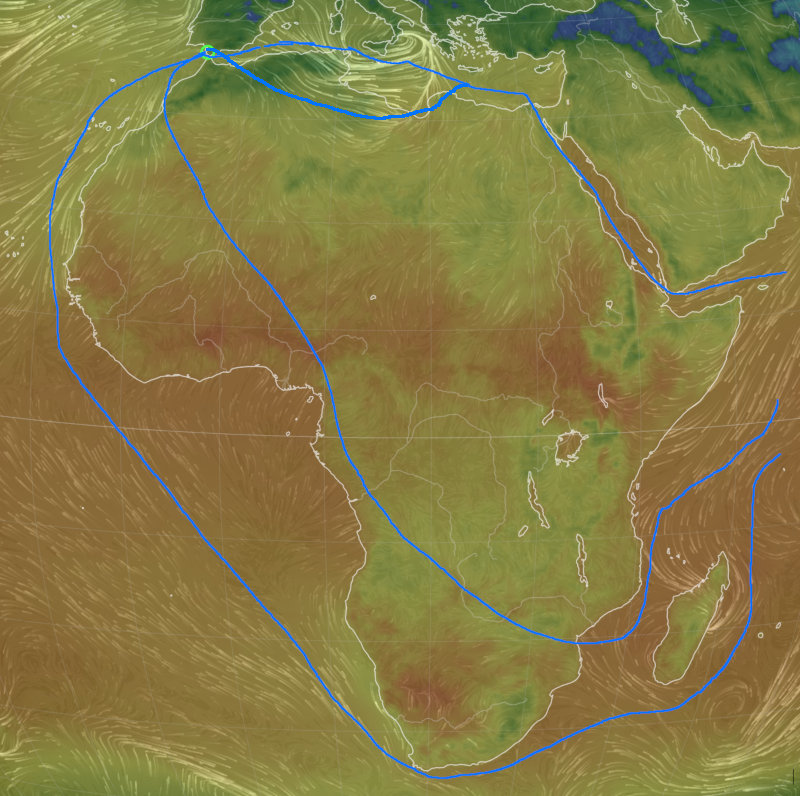

Here we encounter a few of the many difficulties. To start with, we have to cross Egypt over the Suez Canal, which might prove challenging: the area is not far from the Gaza Strip. But next we have to cross the Mediterranean Sea, where we most often find strong West-East winds.

This makes the faster path not always feasible. One alternative path would go around Africa, although it would be hard to reach Cádiz from there. Another interesting possibility goes through Africa, Although drones are severely limited or outright forbidden on many countries. And then we may just skip the worst of Mediterranean winds entering Northern Africa and the Maghreb.

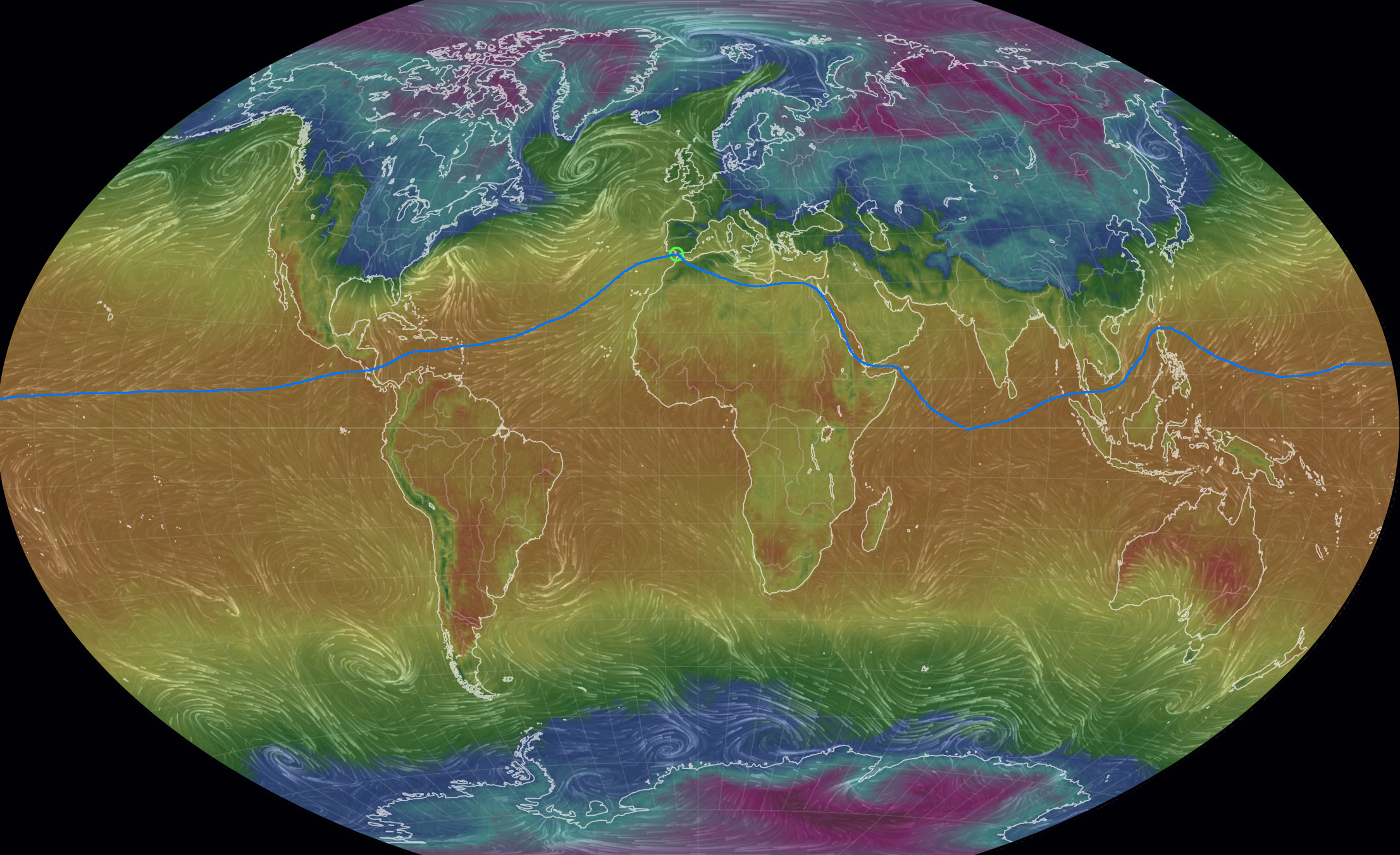

Please find below the full suggested trajectory. It is quite straight: just above 41000 km, not a lot over the equatorial roundabout. Most of what we spend in detours is saved by going above the equator where the parallels are shorter.

At 800 km/day the full trip would take 51 days, or just above 7 weeks. This path is also quite optimistic as we have seen, and full of real-world challenges. We will go over a few of them next.

⛰️ Height

The problem of height is one of the most interesting aspects of the project. Go too high and the payload is reduced greatly; go too low and any sudden change of temperature will drop the drone to the ground. At night the air is colder which may push the Avis to higher altitudes, up to 1 km of difference. Therefore the ship will be constantly moving up and down.

At the beginning of the trip the gas bag will be full, and therefore the Avis will move at higher altitudes, possibly more than 1000 meters high. After several weeks the envelope will have leaked some of the hydrogen, potentially up to 10%, and therefore it will be harder to keep altitude; any hills will have to be surrounded.

📡 Communications

How can we get news from our trusty friend as it flies around the globe? There are several intriguing possibilities which I have learned about.

The first is LoRa, a wide area protocol used by enthusiasts. Sadly coverage is quite irregular, patchy in Central America and Southern Asia, and non-existent in Africa.

The second is SigFox, which has decent worldwide coverage. It requires paying a small amount and purchasing compatible hardware. At some point the network was almost dismantled, but the company was acquired by a third party which appears to be strengthening coverage.

In any case we need a way for the drone to send us telemetry. My nascent Avis Telemetry project may be quite useful to store remote data, and it can also be used to change configuration parameters whenever there is an internet connection.

🪧 Politics

Finally, what are the legal implications of flying an airship drone over foreign air spaces? This very complex area clearly requires in-depth study and careful consideration, and it lies completely out of my depth. The primary objective is just to avoid being shot down since I’m not planning to visit any foreign countries in person, and this article is already long enough; so allow me to just touch over the main issues.

No matter what you have heard, it is legal to fly civilian aircraft. But there are certain regulations that vary wildly between countries. In the EU you have to register drones over 8 kg, as is the case with the Avis Lxxx. It is however illegal to fly drones over visual line-of-sight (VLOS), i.e. not keep them in sight; and to fly at a height above 120 m. Since the plan is to launch from Spain it would not spend a lot of time within the EU.

But is the Avis a drone, or can it be considered a balloon? Balloon regulations tend to be much laxer: in some countries a radar reflector is usually required onboard, presumably so planes can avoid them, and little else. Sending a flight plan in advance might be required for some countries. And in any case it is important to mark the drone clearly as a civil craft, to avoid misunderstandings.

💸 Budget

Can we put a number on the necessary budget for the Avis Lxxx? Hardly. Let me explain.

♺ Material Cost

Most of the materials required should be pretty cheap, like PVA and other plastic coatings. Carbon fiber can also be sourced for a few tens of euros.

Equipment on the other hand is not cheap: for instance ultrasonic sealing machines cost many thousands of euros. Industrial hydrogen generators are another expensive bit. Keep in mind that we need 8000 l of hydrogen; this €10k hydrogen generator would take 5+ days to fill our enclosure.

On the other hand a commercial cylinder with 50 l (200 bar) costs around €130, for a total of more than 8 m³, enough to fill one airship. So we may rethink the need to generate our own hydrogen.

🥼 Trials

A series of trials should establish if the Avis Lxxx is airworthy. It is not enough to find a few parts on AliExpress and say that the project can be done: the actual airship will have to work reliably for weeks, and hardened parts will need to be sourced (or fabricated).

A convenient destination from Spain is the Canary Islands. Another nice place to visit is Canada, where legislation is more lax than in the EU: for instance it is now legal to fly drones beyond visual line-of-sight.

🔬 Research

Most of our funds are needed to investigate possible alternatives for fabrication, and to ensure mission success. Putting together a team of clever people takes time and costs a lot of money. It is hard to estimate just how much years of engineering are needed.

But is a lot of money really necessary? We often find on social media like YouTube really bright people that create really complex projects on their own in a few months. So it is possible that one of these geniuses will replicate this project with a budget of a few thousand euros. Why not? After all there are no great obstacles to any clever maker who is sufficiently determined, and enough of a fool to embark in such a crazy enterprise.

🤔 Conclusion

Yes, it should be possible to fly an airship drone around the world in less than 80 days. There are many challenges that may require time and money to solve, but no fundamental issue that prevents a successful circumnavigation in principle. Personally it has been fun to study the feasibility of the Avis Lxxx project. I hope it was also entertaining to read about it.

🥺 Motivation

Why pursue this project, at all? First, a kid can dream: thought experiments have often moved forward what is considered possible. After all, the original story for “Around the World in 80 Days” is just that, a thought experiment carefully laid out and very well narrated. Jules Verne did not travel but just imagined how it could be done.

Then there are the famed world records: Airbus Zephyr, the work of a giant corporation, holds the current record for air endurance with 67 days. Wouldn’t it be great to snatch it from their cold corporate hands with an independent project?

Then there is the fact that airships are just super cool. Dreamers from Torres Quevedo to Hayao Miyazaki to Google Founder Sergei Brin have been seduced by them.

🙏 Acknowledgements

Thanks to Carlos Santisteban, Juan Searle and many others for their insightful feedback. Thanks to my friends at MakeSpace Madrid for the interesting discussions: in particular David, Pablo, José David, Sink, and Javi who have had to indulge my crazy ideas.

Published on 2026-02-01, last modified on 2026-02-04. Comments, suggestions? Did I miss any obvious issues?

Back to the index.